Chord Theory - Extended Chords

In guitar chord theory part 3 we looked at constructing 7th chords. These are one family of four-note chords. There are other four note chords and this lesson will cover some of them.There are also chords that contain more than four notes. Further notes can be added to triads and 7th chords to create fuller, extended chords. If you're interested in studying jazz harmony, extended chords are a must.

Hopefully this lesson will provide you with a good knowledge base to help you see how more complex chords are constructed on guitar.

Make sure you have a good

knowledge of

the fretboard to supplement this lesson, because I'll only be

showing you the most common chord forms.

Stacking chord tones

Adding tones to a chord root is known as "stacking". So you can have three note chords (triads) all the way up to six and even seven note chords (although obviously on a six string guitar, omissions, such as the 5th, have to be made). Extended chords are generally those chords that stack up more than 4 tones, beyond the 7th.

Below is the natural order of tones when stacking. Remember, chords may include sharp (♯) or flat (♭) tones. For example, a minor 7th chord includes a ♭3 and ♭7, whereas a major 7th chord includes a major 3 and 7.

| Natural | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 13 |

| Flat | - | ♭3 | ♭5 | ♭7 | ♭9 | - | ♭13 |

| Sharp | - | - | ♯5 | - | ♯9 | ♯11 | - |

A few things to note here, when writing or reading chords...

- The 9th is the same as the 2nd

- The 11th is the same as the 4th

- The 13th is the same as the 6th

The former numbers are to represent that tone's position in the hierarchy when it comes to abbreviating chord names. So, in actuality, the 2nd of the scale comes after the 3rd, 5th and 7th because in chord theory it's the 9th. However, there are exceptions which I admit makes it a little awkward when you're trying to learn this stuff. I'll point out these inconsistencies as they arise.

A quick recap for writing the most important chords we've learned so far...- A major triad - symbolized by just the root's letter (e.g. G) or "maj" (e.g. Gmaj) suggests there is a major 3rd and 5th added to the root.

- A minor triad - the root's letter followed by an "m" (e.g. Gm) suggests there is a minor 3rd and 5th added.

- A dominant 7th chord - the root's letter followed by a "7" (e.g. G7) suggests there is a major 3rd, 5th and minor 7th (see part 3 if you're confused) added.

- A major 7th chord - the root's letter followed by "maj7" (e.g. Gmaj7) suggests there is a major 3rd, 5th and major 7th added.

- A minor 7th chord - the root's letter followed by "m7" (e.g. Gm7) suggests there is a minor 3rd, 5th and minor 7th added.

So we're just stacking the intervals up from the root. Once we stack beyond the 7th, we're into extended chord territory!

Let's look at some practical examples.9th chords

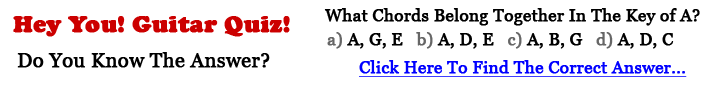

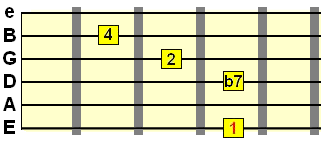

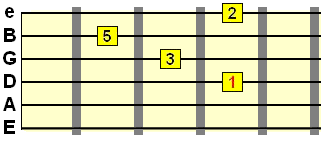

Major 9th

Below are the tones that make up a major 9th (e.g. Gmaj9) chord. The maj9 in the chord name tells us the chord is stacked up to the major 9th tone as follows...

So because the major 9th chord includes all the tones up to the 9th, the 9 is the number used in when writing the chord. Without the 9, it would be maj7 because all the chord tones up to the major 7th would be included.

Below is an example of a major 9th chord (but I've left out the 5th so I can get the other tones in - this is fine)...

Remember, the 2nd becomes the 9th in most chords. You'll rarely see maj9 written as maj2, but even if you do, you'll know 2 and 9 are referencing the same interval.

If you find that you can't include all the tones in the chord for the fingering you've chosen, you can usually leave out the 5th from the chord and it won't lose its character.

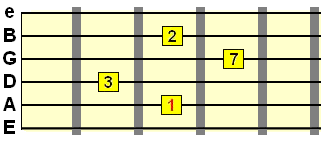

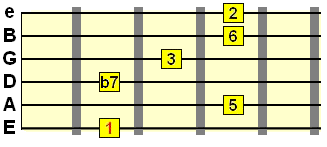

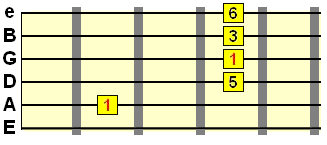

Dominant 9th

We can also extend dominant 7th chords to include the 9th, giving us a dominant 9th chord (e.g. G9)...

So if there's no "maj" in between the chord letter and the number, we know the 7th is a dominant (flat) 7th as opposed to a major 7th.

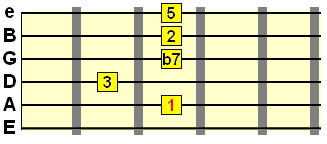

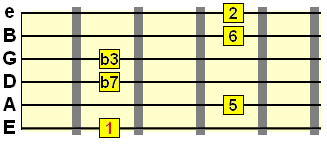

Minor 9th

Apply the same stacking process to minor chords. If we add a 9th to a minor 7th chord we get a minor 9th chord...

This would be abbreviated as "m9" (e.g. Gm9).

11th chords

Here's the order of natural chord tones again for non-scrolling reference...

| Natural/Major | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 13 |

| Flat/Minor | - | ♭3 | ♭5 | ♭7 | ♭9 | - | ♭13 |

| Sharp | - | - | ♯5 | - | ♯9 | ♯11 | - |

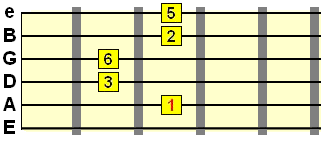

In theory, an 11th chord would include the elements of a dominant 9th chord plus an 11th...

However, it's more common to use the 11th in the context of a suspended (no 3rd) chord, to avoid dissonance. We can still write it as an 11th chord, however (e.g. C11, D11, F11) and doing so helps us distinguish a stacked 11th suspended chord from a standard sus4 chord, which only tends to include up to the b7 (1 4 5 ♭7).

Again, it's fine to leave out the 5th if, for example, the fingering doesn't allow it. Also, if the root is covered by the bass or other instrument, you can leave out the root as a guitarist and free up a finger/fret for other tones.

Unlike the 11th and major 3rd, the 11th and minor 3rd are commonly used together (especially in jazz music), giving us a minor 11th chord...

It's common to leave out the 5th with these trickier fingerings, because in most cases doing so doesn't take away from the chord's overall sound. The 5th is a neutral tone. It's also often difficult to fret all six notes in certain positions.

| It's

beneficial to learn how these chord tones appear right across the

fretboard. This software will make your study time more productive and interesting. |

13th chords

With 13th chords we leave out the 11th because it tends to sound unharmonious as part of the chord (and on a 6 string guitar, it's physically impossible to play all 7 tones!). These are the inconsistencies you have to work around.

Dominant 13th chords

So with G13, for example, the "13" (also the 6th) suggests that the highest tone in the chord is the 13th, and because there is no "add", we can assume there is a flat 7th. It's the fullest stacked dominant chord we can create...

Note that even without the 9th/2nd, it's still often called a 13th chord, as it's a 7th chord with the 13th as the highest tone.

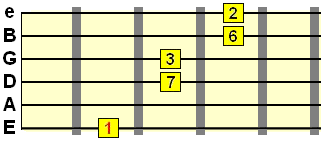

Major 13th chords

And of course, we can build major 13th chords (e.g. Gmaj13, Amaj13 etc.). The "maj" tells us the 7th is a major 7th as opposed to a minor/flat 7th, with the same overall stack of tones...

Another jazzy one there. Again, even if it didn't include the 2nd/9th, we'd still call it a maj13 chord.

Minor 13th

For minor 13th chords, such as Am13 and Gm13, it's just the same, except we flatten the 3rd, because a flat 3rd makes it a minor chord.

Added tone chords

Added tone chords (e.g. Gadd6, Gadd9) occur when there is no 7th, yet the chord includes tones beyond the 7th (9th, 11th, 13th). Think of them as extended chords without a 7th. This gives them a different overall sound.

Let's look at the tones in an added 9th (e.g. Gadd9) chord...

Note the absence of a 7th.

Therefore, if the 7th is not present in the chord's stack, any tone beyond the 7th becomes the added tone. In this case, the added tone is the 9th.

That would be abbreviated as "add9" (e.g. Gadd9).

The same thing applies when adding the 6th/13th to chords with no 7th. Remember, the 6th becomes the 13th in the order of chord tones. So if the 7th is missing, we can note the chord as add6 or add13...

What if both the 9th and 13th tones are added to a chord with no 7th?

Good question! We could write this as add6/9, or add9/6 (e.g. Gadd9/6). The slash is like saying "and also add..."

Note that you'll see the 13th and 6th used interchangeably, as they're both the same tone. I generally see add6 being used more than add13.

To summarise, "add" is like saying "an extended chord (beyond the triad) without a 7th". This applies the same to minor chords (b3) as it does major. E.g. Cmadd9, Cmadd13.More to come...

When learning guitar chord theory, don't get hung up on inconsistencies. People will write chords differently, but I hope the above has given you an insight into the more complex extended chords you can create by stacking up those tones.

In the next lesson we'll bring all this stuff together and use our chord construction knowledge to create alternate chord voicings, not just the same old E/A form barre/movable chords.

In the meantime, make sure you keep on studying chord forms across the fretboard, based on your knowledge of how each chord type is constructed. The best way to do this is to see how chord extensions exist within scales.

| Was this

helpful? Please support this site. I really appreciate it! |

Stay updated

and learn more Sign up to the newsletter for updates and grab your free Uncommon Chords book |

Share your thoughts...

Have any questions, thoughts or ideas about this lesson? Let us know using the comments form below.

Related