Home

> Scales

/ Progressions

> Natural

Minor Progressions

Natural minor also works over sequences of chords in a minor key. We might call these natural minor chord progressions, as we can solo over them using the scale.

Note: Not every minor key progression will be compatible with natural minor, but the vast majority are, especially in popular music.

This lesson will do two things - help you understand where these progressions come from followed by some powerful ear training exercises to help you determine when to use the natural minor scale in your solos. You can skip the theory part if you like, but this knowledge will transfer into other areas of music theory, so at least give it a shot!

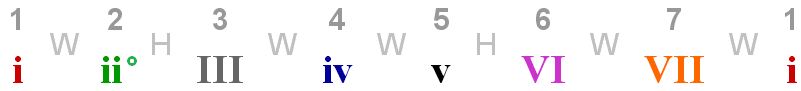

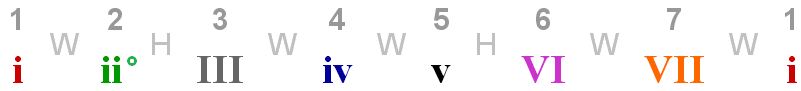

We're basically building chords on each degree of the scale instead of playing single notes, so each degree now marks the root of a new chord.

Each chord in the scale is typically labelled using Roman numerals - lower case for the minor chords (except ii which we'll come to in a moment) and upper case for the major chords...

Tip: take note of the intervals between each chord. For example, there's a whole step between the 7th and tonic chord. There's a whole step between the 6th and 7th chords. A half step between the 5 and 6 chords etc.

i is known as the tonic chord. You could call this "home" (albeit an unhappy one in minor keys!). This is the chord that determines the key of the progression, and therefore the root we use when playing the natural minor scale. For example, if the tonic was D minor, the key of the progression would also be D minor and therefore the scale's root would need to be on D.

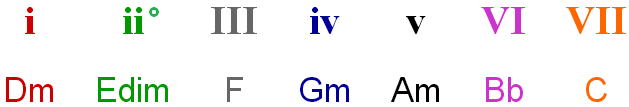

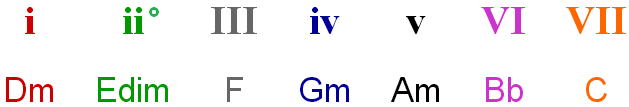

So, as each chord is built on a degree of the natural minor scale, we should be able to use our knowledge of the scale's intervals to work out, first the notes of the scale and therefore what each chord would be in a given key. Let's stick with D minor in this example...

Click to hear

Note: Edim stands for E diminished. The circle next to the numeral also indicates the chord is diminished. You can learn all about diminished chords in their own lesson. Don't worry about it right now as we won't be using it in this lesson because most natural minor progressions don't use it.

From this scale, we can pick out different combinations of chords to create a D natural minor chord progression. For example...

Click to hear

That's a very typical movement over which we could use the D natural minor scale. The scale also works over the Bb (B flat) and C major chords because they are part of this D minor chord scale as shown earlier. To be more specific, all three chords contain notes from the D natural minor scale.

We don't have to start on the tonic either...

Click to hear

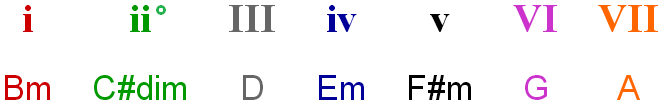

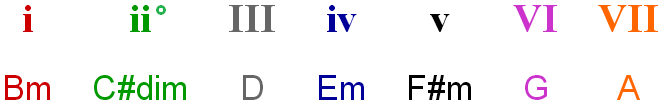

It's important to hear these progressions as relative movements that can be used in any key. If the tonic chord was Bm instead of Dm, for example, how would that change the other chords in the scale, based on its intervals?

Click to hear

That means the chords in the above i VI VII progression would change accordingly...

Click to hear

So the main thing to understand here is that the Roman numerals represent a chord progression drawn from the intervals of a parent scale (such as natural minor).

When you hear someone say "1 4 5 in A minor" you'll know they mean the 1st, 4th and 5th chords from the A minor scale.

Now we understand where these progressions come from, it's time to train our ear to recognising a natural minor progression when we hear it, so we'll know when to use the scale.

I've given examples in three of the most common minor keys - A, E and C.

The idea is to train your ear to recognise these movements when you hear them, so you'll have a better idea of when to use the natural minor scale in your soloing. You'll hear that "natural minor sound" dominate the music.

Tip: To get in the right key, the root note (1) of the scale you're playing should match with the root of the tonic chord (e.g. A minor = A, E minor = E etc.)

Let's start with the strongest two-chord movements that imply natural minor. Many popular minor key songs only use the two chords listed below. When you hear two chords played like this, it's a signal that natural minor (and of course minor pentatonic and its blues variations) is a good scale choice. In fact, in most cases the vocals will also be using this scale.

To fully internalise them, I recommend playing the scale along to the tracks. And hey, it should be a more fun way to explore the scale than playing without accompaniment.

Click the chord links within the table (right click and save to download) to hear them.

Now moving on to common three and four chord movements. Get to know them well - you'll hear them in so many songs!

Most minor key progressions start on the tonic, but sometimes you'll hear them start on another chord in the scale. For example, the tonic could appear at the end: VI / VII / i or even in the middle: v / i / VI

However, what you're listening for are the intervals or relationships between the chords that imply natural minor, no matter what order they're in. The more you listen to and internalise the tracks above, the more your ear will develop the ability to identify that "natural minor sound" in the songs you hear and write.

For more on ear training, take a look at the free 10 day crash course by Easy Ear Training. They will help you make that crucial connection between what you hear and what you play.

Share your thoughts...

Have any questions, thoughts or ideas about this lesson? Let us know using the comments form below.

Natural Minor Chord Progressions - Powerful Ear Training

In the introductory natural minor scale lesson, we learned that the scale can be connected to minor chords because of its intervals (i.e. the 1, b3 and 5 from the scale make up a minor chord).Natural minor also works over sequences of chords in a minor key. We might call these natural minor chord progressions, as we can solo over them using the scale.

Note: Not every minor key progression will be compatible with natural minor, but the vast majority are, especially in popular music.

This lesson will do two things - help you understand where these progressions come from followed by some powerful ear training exercises to help you determine when to use the natural minor scale in your solos. You can skip the theory part if you like, but this knowledge will transfer into other areas of music theory, so at least give it a shot!

Theory - The Natural Minor Chord Scale

Natural minor has its own "chord scale" based on its intervals. So you need to know the scale's intervals before you can grasp this concept - W H W W H W WWe're basically building chords on each degree of the scale instead of playing single notes, so each degree now marks the root of a new chord.

Each chord in the scale is typically labelled using Roman numerals - lower case for the minor chords (except ii which we'll come to in a moment) and upper case for the major chords...

Tip: take note of the intervals between each chord. For example, there's a whole step between the 7th and tonic chord. There's a whole step between the 6th and 7th chords. A half step between the 5 and 6 chords etc.

i is known as the tonic chord. You could call this "home" (albeit an unhappy one in minor keys!). This is the chord that determines the key of the progression, and therefore the root we use when playing the natural minor scale. For example, if the tonic was D minor, the key of the progression would also be D minor and therefore the scale's root would need to be on D.

So, as each chord is built on a degree of the natural minor scale, we should be able to use our knowledge of the scale's intervals to work out, first the notes of the scale and therefore what each chord would be in a given key. Let's stick with D minor in this example...

Click to hear

Note: Edim stands for E diminished. The circle next to the numeral also indicates the chord is diminished. You can learn all about diminished chords in their own lesson. Don't worry about it right now as we won't be using it in this lesson because most natural minor progressions don't use it.

From this scale, we can pick out different combinations of chords to create a D natural minor chord progression. For example...

Click to hear

That's a very typical movement over which we could use the D natural minor scale. The scale also works over the Bb (B flat) and C major chords because they are part of this D minor chord scale as shown earlier. To be more specific, all three chords contain notes from the D natural minor scale.

We don't have to start on the tonic either...

Click to hear

It's important to hear these progressions as relative movements that can be used in any key. If the tonic chord was Bm instead of Dm, for example, how would that change the other chords in the scale, based on its intervals?

Click to hear

That means the chords in the above i VI VII progression would change accordingly...

Click to hear

So the main thing to understand here is that the Roman numerals represent a chord progression drawn from the intervals of a parent scale (such as natural minor).

When you hear someone say "1 4 5 in A minor" you'll know they mean the 1st, 4th and 5th chords from the A minor scale.

Now we understand where these progressions come from, it's time to train our ear to recognising a natural minor progression when we hear it, so we'll know when to use the scale.

Ear Training - Natural Minor Chord Progressions Charts

Below are some useful charts with audio showing you some common natural minor progressions, around which countless songs, old and new, have been written (whether intentionally or not!).I've given examples in three of the most common minor keys - A, E and C.

The idea is to train your ear to recognise these movements when you hear them, so you'll have a better idea of when to use the natural minor scale in your soloing. You'll hear that "natural minor sound" dominate the music.

Tip: To get in the right key, the root note (1) of the scale you're playing should match with the root of the tonic chord (e.g. A minor = A, E minor = E etc.)

Let's start with the strongest two-chord movements that imply natural minor. Many popular minor key songs only use the two chords listed below. When you hear two chords played like this, it's a signal that natural minor (and of course minor pentatonic and its blues variations) is a good scale choice. In fact, in most cases the vocals will also be using this scale.

To fully internalise them, I recommend playing the scale along to the tracks. And hey, it should be a more fun way to explore the scale than playing without accompaniment.

Click the chord links within the table (right click and save to download) to hear them.

| ↓ Key | i VI | i v | i III |

| Am | Am / F | Am / Em | Am / C |

| Em | Em / C | Em / Bm | Em / G |

| Cm | Cm / Ab | Cm / Gm | Cm / Eb |

Now moving on to common three and four chord movements. Get to know them well - you'll hear them in so many songs!

| ↓ Key | i VI VII | i III VII VI | i VII iv VI | i v VI VII | i v VII iv | i v iv VII |

| Am | Am / F / G | Am / C / G / F | Am / G / Dm / F | Am / Em / F / G | Am / Em / G / Dm | Am / Em / Dm / G |

| Em | Em / C / D | Em / G / D / C | Em / D / Am / C | Em / Bm / C / D | Em / Bm / D / Am | Em / Bm / Am / D |

| Cm | Cm / Ab / Bb | Cm / Eb / Bb / Ab | Cm / Bb / Fm / Ab | Cm / Gm / Ab / Bb | Cm / Gm / Bb / Fm | Cm / Gm / Fm / Bb |

Most minor key progressions start on the tonic, but sometimes you'll hear them start on another chord in the scale. For example, the tonic could appear at the end: VI / VII / i or even in the middle: v / i / VI

However, what you're listening for are the intervals or relationships between the chords that imply natural minor, no matter what order they're in. The more you listen to and internalise the tracks above, the more your ear will develop the ability to identify that "natural minor sound" in the songs you hear and write.

For more on ear training, take a look at the free 10 day crash course by Easy Ear Training. They will help you make that crucial connection between what you hear and what you play.

| Was this

helpful? Please support this site. I really appreciate it! |

Stay updated

and learn more Sign up to the newsletter for updates and grab your free Uncommon Chords book |

Share your thoughts...

Have any questions, thoughts or ideas about this lesson? Let us know using the comments form below.