Home

> Progressions

> Relative Key

As a lead player, being able to recognise when key changes occur will help you choose the right scales/notes for your solo.

This lesson will introduce you to the mechanics of key changes (often called modulation) starting with the most natural sounding type of modulation - changing between relative keys. This is a good place to start because, as we'll discover, both these keys share the same scale and therefore chords.

Watch the presentation below for the basic info, with more help further down the page...

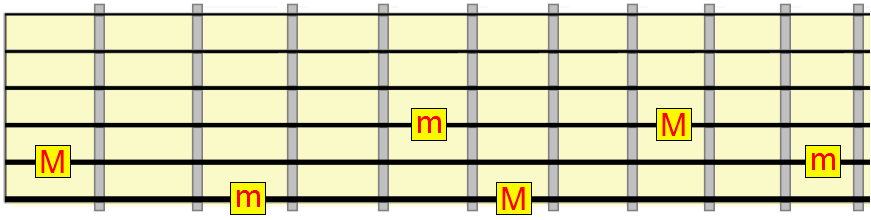

Relative major/minor chords are always a minor 3rd interval (whole + half step) apart, with the minor chord below the major. That's the equivalent of 3 frets on the fretboard. So we have: min - W H - Maj

So to get from a minor chord to its relative major, you move up a minor 3rd interval from its root.

To get from a major chord to its relative minor, you move down a whole and half step from its root.

The table below shows this relative relationship in several keys.

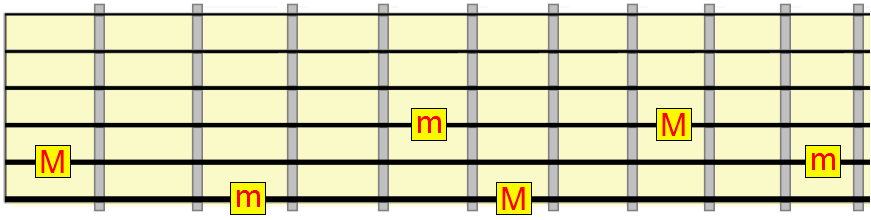

The diagram below shows you how the relationship between relative major (M) and minor (m) chord root notes would appear on the fretboard. So wherever the root of your chord shape is on the neck, you should be able to find its relative chord in close proximity...

Remember that key signature is not the same as key center. Key signature is about specific notes used in the chords/scale of the progression. Key center is about where the progression resolves in that scale... which chord is considered "home".

Both C major and A minor, for example, share the same key signature (since they share notes from the same diatonic scale, just starting on a different degree). But if you built a progression around a Cmaj tonic, for example, it would have a different key center to a progression built around an Am tonic. They both act as independent points of resolution even though they share notes from the same "parent" scale (C major).

Regardless, what matters is that you can visualise and hear the relationship between relative major and minor tonic chords. Then, we can move on to using/identifying them in progressions.

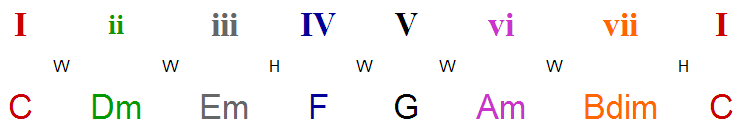

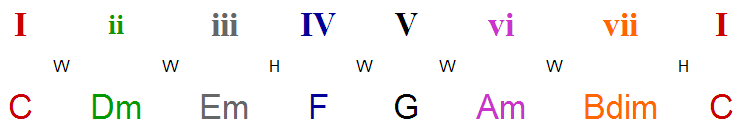

Here's how the scale would look in C major...

So we could have a progression of: Cmaj / Fmaj / Dm / Gmaj (I IV ii V) ...and Gmaj would resolve nicely back to Cmaj. Cmaj is therefore the tonic or "home" of this progression. There's a certain musical "gravity" that pulls us towards it.

That, in a nutshell, is what key center is all about. No need to overcomplicate it. It's all about resolution.

However, we could also resolve from Gmaj to the relative minor key of Am, Am being the vi chord of the harmonized C major scale.

Technically, when we establish a new tonic like this, we should call that new tonic chord 1 or i (lower case numeral for minor chords). But that would mean renumbering the scale in relation to that new 1 chord. I (and many musicians in fact) prefer to just see the relaitve minor tonic as the 6 chord of the major scale.

One scale, two relative tonics, in other words.

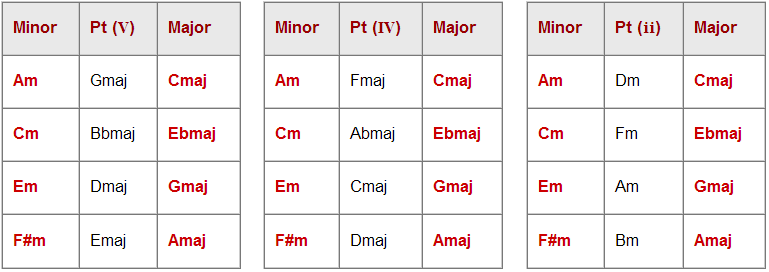

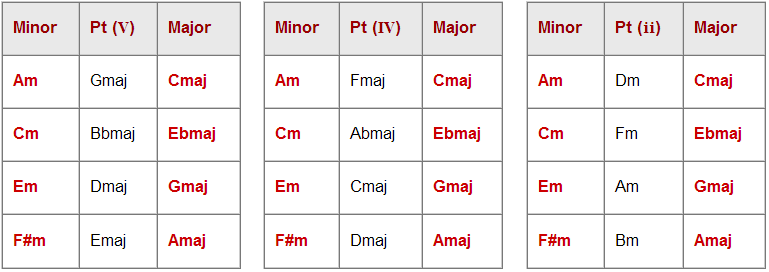

In the table below, we have three potential pre-tonic chords - the V, IV and ii - for moving from the minor key to its relative major...

In the audio clips, you'll hear the minor progression played twice before changing to the relative major key, again played twice before resolving back to the minor tonic. This will demonstrate how this relative key shift works in practice.

Note: you obviously don't have to repeat the same progression in the major key as you did in minor. I've just used the same chords to demonstrate how they can still sound natural when a relative key change is used.

Progressions also don't always start on the tonic. However, when getting to know this stuff, starting on the tonic will help train your ear to a specific key centre.

So we might change from a major key verse to a relative minor bridge (e.g. for just four measures) and then return to the relative major key for the chorus. This is a technique commonly employed in popular music and helps to structurally and dynamically break up the song.

Examples...

Note: that second example demonstrates how we don't have to start on the tonic chord to affirm the new key centre.

Share your thoughts...

Have any questions, thoughts or ideas about this lesson? Let us know using the comments form below.

Using Relative Key Changes to Make More Interesting Music

As a songwriter, key changes are a really effective way of making your songs sound structurally and dynamically more interesting.As a lead player, being able to recognise when key changes occur will help you choose the right scales/notes for your solo.

This lesson will introduce you to the mechanics of key changes (often called modulation) starting with the most natural sounding type of modulation - changing between relative keys. This is a good place to start because, as we'll discover, both these keys share the same scale and therefore chords.

Watch the presentation below for the basic info, with more help further down the page...

Relative Key Chart and Diagrams

First, we need to understand the relationship between relative major and minor chords.Relative major/minor chords are always a minor 3rd interval (whole + half step) apart, with the minor chord below the major. That's the equivalent of 3 frets on the fretboard. So we have: min - W H - Maj

So to get from a minor chord to its relative major, you move up a minor 3rd interval from its root.

To get from a major chord to its relative minor, you move down a whole and half step from its root.

The table below shows this relative relationship in several keys.

| Major | Cmaj | Dmaj | Emaj | Fmaj | Gmaj | Amaj | Bmaj |

| Minor | Am | Bm | C♯m | Dm | Em | F♯m | G♯m |

The diagram below shows you how the relationship between relative major (M) and minor (m) chord root notes would appear on the fretboard. So wherever the root of your chord shape is on the neck, you should be able to find its relative chord in close proximity...

But why "relative"? (Warning: for the theory heads only!)

This isn't so important to know if you're not that interested in theory. But in the context of key, relative major and minor keys are said to share the same key signature. The only difference between the two is they represent a different tonal center, i.e. they act as independent tonic chords of their own keys.Remember that key signature is not the same as key center. Key signature is about specific notes used in the chords/scale of the progression. Key center is about where the progression resolves in that scale... which chord is considered "home".

Both C major and A minor, for example, share the same key signature (since they share notes from the same diatonic scale, just starting on a different degree). But if you built a progression around a Cmaj tonic, for example, it would have a different key center to a progression built around an Am tonic. They both act as independent points of resolution even though they share notes from the same "parent" scale (C major).

Regardless, what matters is that you can visualise and hear the relationship between relative major and minor tonic chords. Then, we can move on to using/identifying them in progressions.

Changing Between Relative Major and Minor Keys

The only difference between a relative major and minor key is we're resolving the progression to a different chord in the same scale - I (1) for the major tonic and vi (6) for the minor tonic.Here's how the scale would look in C major...

So we could have a progression of: Cmaj / Fmaj / Dm / Gmaj (I IV ii V) ...and Gmaj would resolve nicely back to Cmaj. Cmaj is therefore the tonic or "home" of this progression. There's a certain musical "gravity" that pulls us towards it.

That, in a nutshell, is what key center is all about. No need to overcomplicate it. It's all about resolution.

However, we could also resolve from Gmaj to the relative minor key of Am, Am being the vi chord of the harmonized C major scale.

Technically, when we establish a new tonic like this, we should call that new tonic chord 1 or i (lower case numeral for minor chords). But that would mean renumbering the scale in relation to that new 1 chord. I (and many musicians in fact) prefer to just see the relaitve minor tonic as the 6 chord of the major scale.

One scale, two relative tonics, in other words.

Use pre-tonic chords for smoother transition

Pre-tonic (Pt) chords are chords that come just before the tonic, with their main function being to aid resolution (think of them like signposts that tell you you're almost home!). Some chords create a stronger pull to a tonic than others, and can help us transition smoothly between keys.In the table below, we have three potential pre-tonic chords - the V, IV and ii - for moving from the minor key to its relative major...

Examples of relative key modulation

Below are some examples (with audio clips) of major I - minor vi key changes using typical progressions you'll hear in countless songs old and new. I've also highlighted the "pre-tonic" (Pt) chord...In the audio clips, you'll hear the minor progression played twice before changing to the relative major key, again played twice before resolving back to the minor tonic. This will demonstrate how this relative key shift works in practice.

| Minor Key | Pt | Major Key | Audio | |||

| Am | Fmaj | Gmaj | Cmaj | Fmaj | Gmaj | Click here |

| Em | Cmaj | Am | Gmaj | Cmaj | Am | Click here |

| F#m | Bm | Dmaj | Amaj | Bm | Dmaj | Click here |

Note: you obviously don't have to repeat the same progression in the major key as you did in minor. I've just used the same chords to demonstrate how they can still sound natural when a relative key change is used.

Progressions also don't always start on the tonic. However, when getting to know this stuff, starting on the tonic will help train your ear to a specific key centre.

Bridge tonicization

Don't be fooled by the jargon! Tonicization is just another way of saying "a temporary change in key/tonic".So we might change from a major key verse to a relative minor bridge (e.g. for just four measures) and then return to the relative major key for the chorus. This is a technique commonly employed in popular music and helps to structurally and dynamically break up the song.

Examples...

| Verse | Bridge | Chorus | Audio | |||||

| Cmaj | Dm | Gmaj | Am | Em | Fmaj | Gmaj | Cmaj | Click here |

| Gmaj | Dmaj | Cmaj | Am | Em | Am | Cmaj | Gmaj | Click here |

Note: that second example demonstrates how we don't have to start on the tonic chord to affirm the new key centre.

Other ideas to try

Use relative modulation to...- Play an intro in a different relative key to the verse.

- Break up a more kinetic verse. For example Cmaj / Gmaj / Cmaj / Fmaj / Am / E7 / Am / E7

- Play a middle eight (a kind of interlude after a couple of choruses).

- Play a minor key rendition of the chorus (usually after several regular choruses). This is often called reharmonization.

- Play an outro in a different key to the preceding section.

| Was this

helpful? Please support this site. I really appreciate it! |

Stay updated

and learn more Sign up to the newsletter for updates and grab your free Uncommon Chords book |

Share your thoughts...

Have any questions, thoughts or ideas about this lesson? Let us know using the comments form below.