Home

> Advice > Why Learn Intervals

In music, there are two ways to label pitches - alphabetical notes (A - G) and numerical intervals (1 - 7). Most guitarists take some time to learn the notes of the musical alphabet and where each note lies on each string/fret. But while this is valuable, the benefits of knowing intervals is often overlooked.

People often ask me about the numbers I use in many of my diagrams. If you're not familiar with intervals, they can look a bit strange - e.g. ♭7, ♯4, ♭5 etc.

Before we learn more about what these labels mean, we first need to understand why it's worth just as much, if not more of our time to learn intervals as it is notes.

In short, both labels serve different functions in terms of how they "measure" pitch.

For example, if you see C major (or Cmaj) written down, you'd typically find C on the neck first and build a major fingering shape around that root.

Similarly, if you wanted to play A minor pentatonic, you would most likely find A on the neck first and build the minor pentatonic scale pattern from there.

We could also work out the individual notes that make up a chord or scale, above the root. For example, Cmaj contains the notes C, E and G.

The A minor pentatonic scale contains the notes A, C, D, E and G.

But as I'll get to in a moment, this isn't really necessary (and it's very time consuming).

So these alphabetical note labels are best used to locate single, specific pitches, known as absolute pitch.

Intervals occur between two pitches. They are a way of measuring the distance between notes. Therefore intervals are about relative pitch - the relationship between notes.

Intervals are, therefore, the true building blocks of music, since music is made when two or more pitches either harmonise (play together) or form a melody (move from one pitch to another).

For example, going back to our C major chord, its interval formula would be 1, 3, 5 (don't worry if you don't know why we use 3 and 5, that'll come later).

However, the 3 and 5 are relative to the root, so whichever root we use - C, D, E, F etc., the formula of the major chord will always be 1, 3, 5, regardless of how the note labels change.

And I'm not just talking about memorising a fingering. It's about being able to identify each pitch within a chord or scale so you can confidently target specific pitches on any root or in any key, without having to know its note labels.

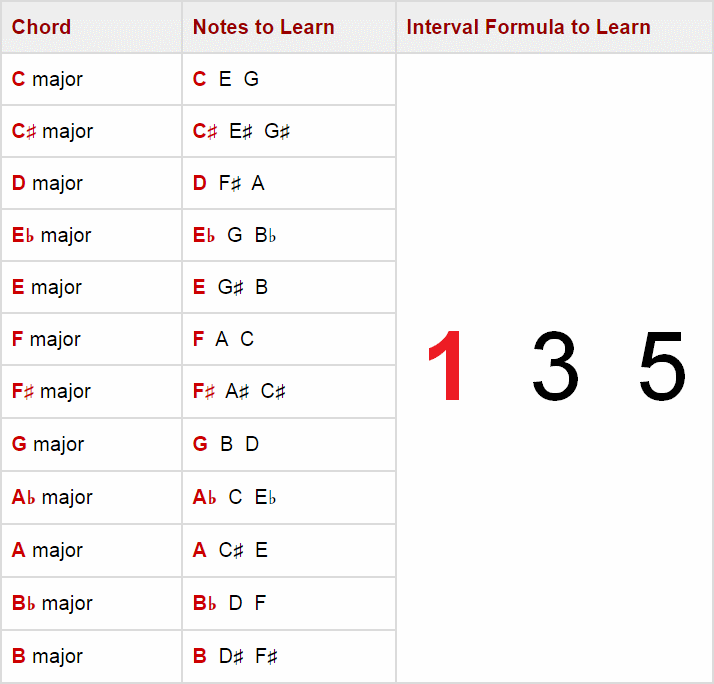

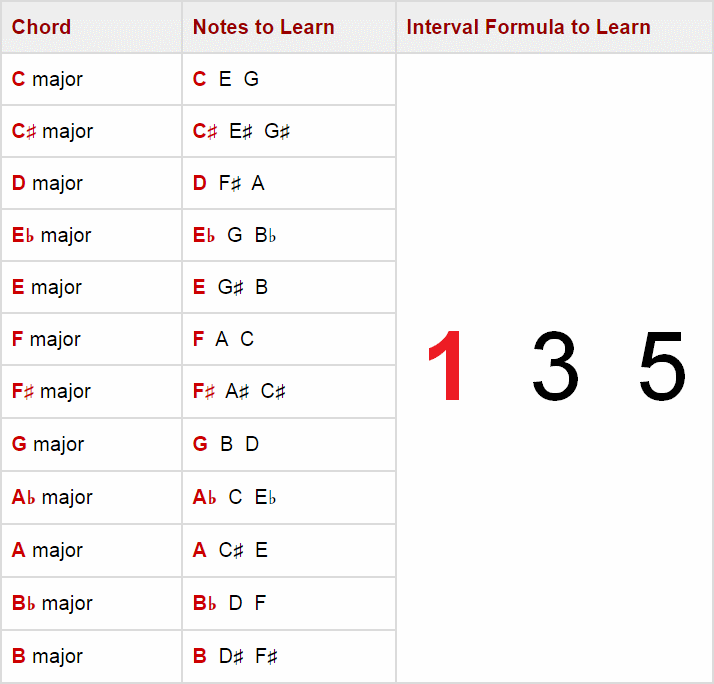

If you're scratching your head (I don't blame you! Bear with me!), this table may help to clarify why knowing intervals is like a "short cut" to knowing chords and scales in every key...

So as you can see, every single major chord, no matter what its notes, can be referenced using the interval formula 1 3 5. Even though they all contain different notes, they can all be seen as part of the same interval family.

The only thing that changes is the root, and therefore the overall pitch (higher/lower) of the chord. But the chord itself looks and even sounds the same, once you learn to see and hear music in intervallic terms.

In purely intervallic terms, C major is the same as E major, F major, G major etc.

In purely intervallic terms, A minor pentatonic is the same as B minor pentatonic, E minor pentatonic, G minor pentatonic etc.

Once you learn how an interval formula appears as a uniform, repeating pattern on the guitar neck, all you need to do is move it to the appropriate root or "starting position". The pattern never changes its structure, its notes never change their relative position.

In fact, that's why we have movable scale patterns and chord shapes - it's really just a bunch of related intervals that make the same sound (hence why we use the same numbers), just higher or lower in pitch, depending on the root we're using.

The movement/distance between 1 and 3 in interval terms is the same whether we're playing C and E, D and F♯ or G and B.

All you really need to know in terms of notes is the root of the chord or scale you're playing, a reference point for starting your pattern or shape, and you'll already know this root because it's right there in the chord name (Cmaj, A minor pentatonic). The rest is all relative interval patterns that you only need to learn once for each chord or scale "family".

You'll start to see the entire neck as one big connected roadmap. Chords, arpeggios and scales will merge into the same musical expression. You'll see a connection between chords and their related scales, and vice versa.

This connection will reveal itself in many ways as you progress in your learning.

For example, knowing intervals allows you to see that 1, 3 and 5 of the major chord exist in the following scales...

It would be far more difficult to see this relationship if you learned each scale purely by its notes, because the notes would be different depending on the root you were playing the scale on. The pattern would be hidden in the alphabet soup!

In short, intervals show you how different musical elements - melody and harmony - are intrinsically related, no matter where you play them.

Most musicians will never have the ability to name a pitch or group of pitches they hear, without any other reference, purely by note, known as absolute pitch recognition. It's a very rare skill and not necessary to have.

But being able to identify intervals by ear, known as relative pitch recognition, is something anyone can learn given a little practice. The value of having this skill is that you'll be able to pick up music purely by ear.

Even if you can't find the exact key it's played in, you'll be able to hear and replicate the movement, the relationship between notes - that's what makes the music happen.

Relative pitch is far more valuable to master than absolute pitch, both visually and auditorily. Intervals are what we use to turn notes into music.

When you're ready, start learning more about intervals here.

Share your thoughts...

Have any questions, thoughts or ideas about this lesson? Let us know using the comments form below.

FAQ: Why Should I Learn Intervals?

In music, there are two ways to label pitches - alphabetical notes (A - G) and numerical intervals (1 - 7). Most guitarists take some time to learn the notes of the musical alphabet and where each note lies on each string/fret. But while this is valuable, the benefits of knowing intervals is often overlooked.

People often ask me about the numbers I use in many of my diagrams. If you're not familiar with intervals, they can look a bit strange - e.g. ♭7, ♯4, ♭5 etc.

Before we learn more about what these labels mean, we first need to understand why it's worth just as much, if not more of our time to learn intervals as it is notes.

In short, both labels serve different functions in terms of how they "measure" pitch.

Notes = Absolute Pitch

Each pitch we can create on guitar can be given an alphabetical label, A through G. This is primarily useful for finding a chord or scale root.For example, if you see C major (or Cmaj) written down, you'd typically find C on the neck first and build a major fingering shape around that root.

Similarly, if you wanted to play A minor pentatonic, you would most likely find A on the neck first and build the minor pentatonic scale pattern from there.

We could also work out the individual notes that make up a chord or scale, above the root. For example, Cmaj contains the notes C, E and G.

The A minor pentatonic scale contains the notes A, C, D, E and G.

But as I'll get to in a moment, this isn't really necessary (and it's very time consuming).

So these alphabetical note labels are best used to locate single, specific pitches, known as absolute pitch.

Intervals = Relative Pitch

Intervals are a slightly different way of finding pitches on the neck and have more to do with musical relationships.Intervals occur between two pitches. They are a way of measuring the distance between notes. Therefore intervals are about relative pitch - the relationship between notes.

Intervals are, therefore, the true building blocks of music, since music is made when two or more pitches either harmonise (play together) or form a melody (move from one pitch to another).

For example, going back to our C major chord, its interval formula would be 1, 3, 5 (don't worry if you don't know why we use 3 and 5, that'll come later).

However, the 3 and 5 are relative to the root, so whichever root we use - C, D, E, F etc., the formula of the major chord will always be 1, 3, 5, regardless of how the note labels change.

"So How Is This Useful?"

Instead of having to learn the notes that make up every single chord and scale, across all 12 roots, intervals allow you to learn in movable patterns and shapes.And I'm not just talking about memorising a fingering. It's about being able to identify each pitch within a chord or scale so you can confidently target specific pitches on any root or in any key, without having to know its note labels.

If you're scratching your head (I don't blame you! Bear with me!), this table may help to clarify why knowing intervals is like a "short cut" to knowing chords and scales in every key...

So as you can see, every single major chord, no matter what its notes, can be referenced using the interval formula 1 3 5. Even though they all contain different notes, they can all be seen as part of the same interval family.

The only thing that changes is the root, and therefore the overall pitch (higher/lower) of the chord. But the chord itself looks and even sounds the same, once you learn to see and hear music in intervallic terms.

In purely intervallic terms, C major is the same as E major, F major, G major etc.

In purely intervallic terms, A minor pentatonic is the same as B minor pentatonic, E minor pentatonic, G minor pentatonic etc.

Once you learn how an interval formula appears as a uniform, repeating pattern on the guitar neck, all you need to do is move it to the appropriate root or "starting position". The pattern never changes its structure, its notes never change their relative position.

In fact, that's why we have movable scale patterns and chord shapes - it's really just a bunch of related intervals that make the same sound (hence why we use the same numbers), just higher or lower in pitch, depending on the root we're using.

The movement/distance between 1 and 3 in interval terms is the same whether we're playing C and E, D and F♯ or G and B.

All you really need to know in terms of notes is the root of the chord or scale you're playing, a reference point for starting your pattern or shape, and you'll already know this root because it's right there in the chord name (Cmaj, A minor pentatonic). The rest is all relative interval patterns that you only need to learn once for each chord or scale "family".

But It's Not Just About Saving Time

Learn to see the fretboard like this and something quite amazing will happen...You'll start to see the entire neck as one big connected roadmap. Chords, arpeggios and scales will merge into the same musical expression. You'll see a connection between chords and their related scales, and vice versa.

This connection will reveal itself in many ways as you progress in your learning.

For example, knowing intervals allows you to see that 1, 3 and 5 of the major chord exist in the following scales...

- Major pentatonic - 1 2 3 5 6

- Major scale - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

- Mixolydian - 1 2 3 4 5 6 b7

- Lydian - 1 2 3 #4 5 6 7

- Phrygian Dominant - 1 b2 3 4 5 b6 b7

It would be far more difficult to see this relationship if you learned each scale purely by its notes, because the notes would be different depending on the root you were playing the scale on. The pattern would be hidden in the alphabet soup!

In short, intervals show you how different musical elements - melody and harmony - are intrinsically related, no matter where you play them.

Intervals Are the Key To Unlocking Amazing Ear Skills

Intervals form on the guitar neck as movable patterns. But we can also use intervals to help us with ear training.Most musicians will never have the ability to name a pitch or group of pitches they hear, without any other reference, purely by note, known as absolute pitch recognition. It's a very rare skill and not necessary to have.

But being able to identify intervals by ear, known as relative pitch recognition, is something anyone can learn given a little practice. The value of having this skill is that you'll be able to pick up music purely by ear.

Even if you can't find the exact key it's played in, you'll be able to hear and replicate the movement, the relationship between notes - that's what makes the music happen.

"So Will I Ever Need to Know The Notes of a Chord or Scale?"

It really isn't necessary. As I mentioned, the value in knowing the notes on the neck is to be able to find a root, a single reference point for a pattern or shape. The rest is all about interval formulas.Relative pitch is far more valuable to master than absolute pitch, both visually and auditorily. Intervals are what we use to turn notes into music.

When you're ready, start learning more about intervals here.

| Was this

helpful? Please support this site. I really appreciate it! |

Stay updated

and learn more Sign up to the newsletter for updates and grab your free Uncommon Chords book |

Share your thoughts...

Have any questions, thoughts or ideas about this lesson? Let us know using the comments form below.

< More Guitar Playing Advice