Jump to...

Overview | Stacking 3rds | Triad Fragments | Merging Horizontal & Vertical

Arpeggios From Scales - An Overview

Arpeggios are one way of expressing a chord quality.

In its most basic form, an arpeggio sequence would follow the natural hierarchy of intervals that make up the implied chord, with the triad at the base, followed by the 7th and then any extensions with which we might wish to further colour the chord.

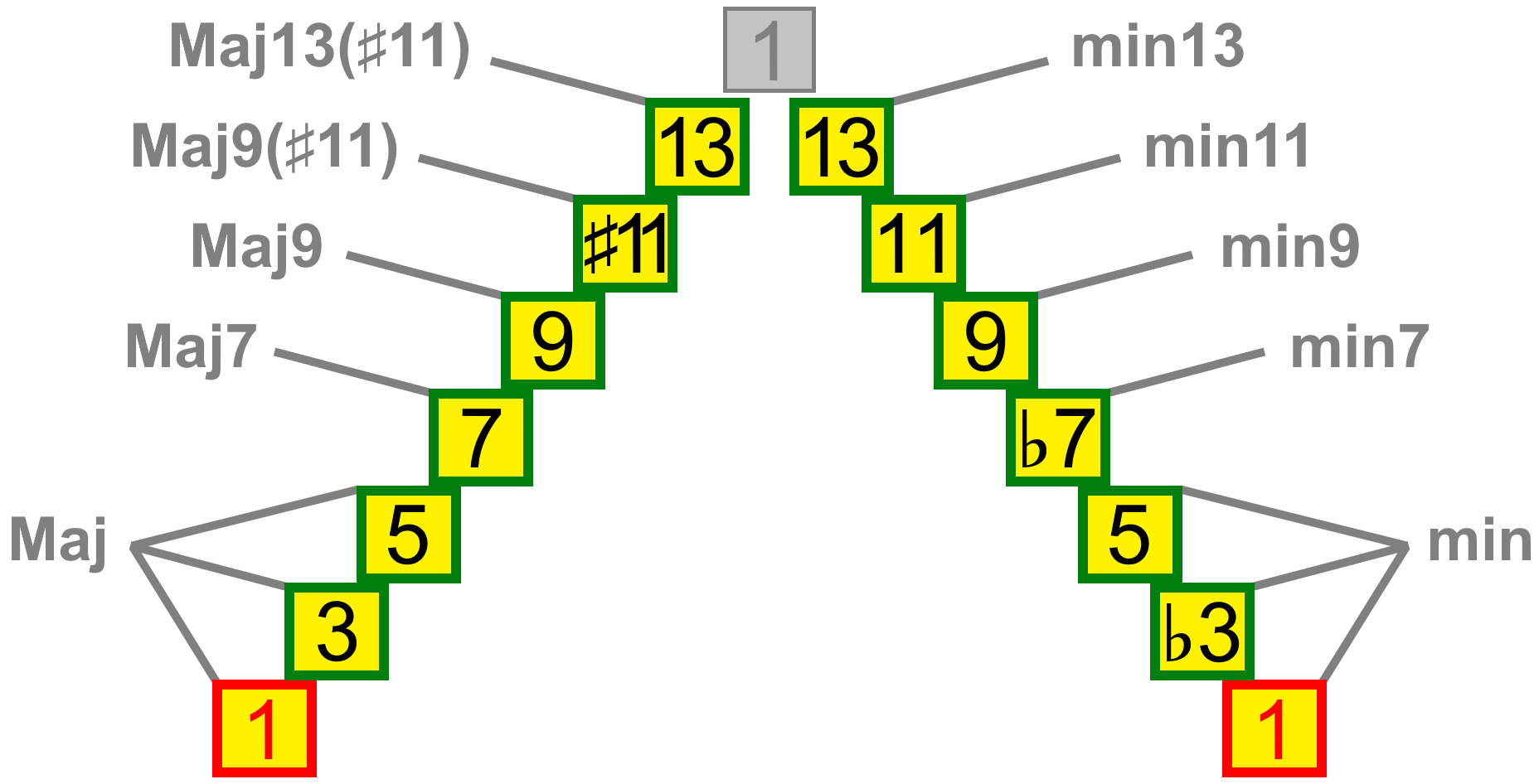

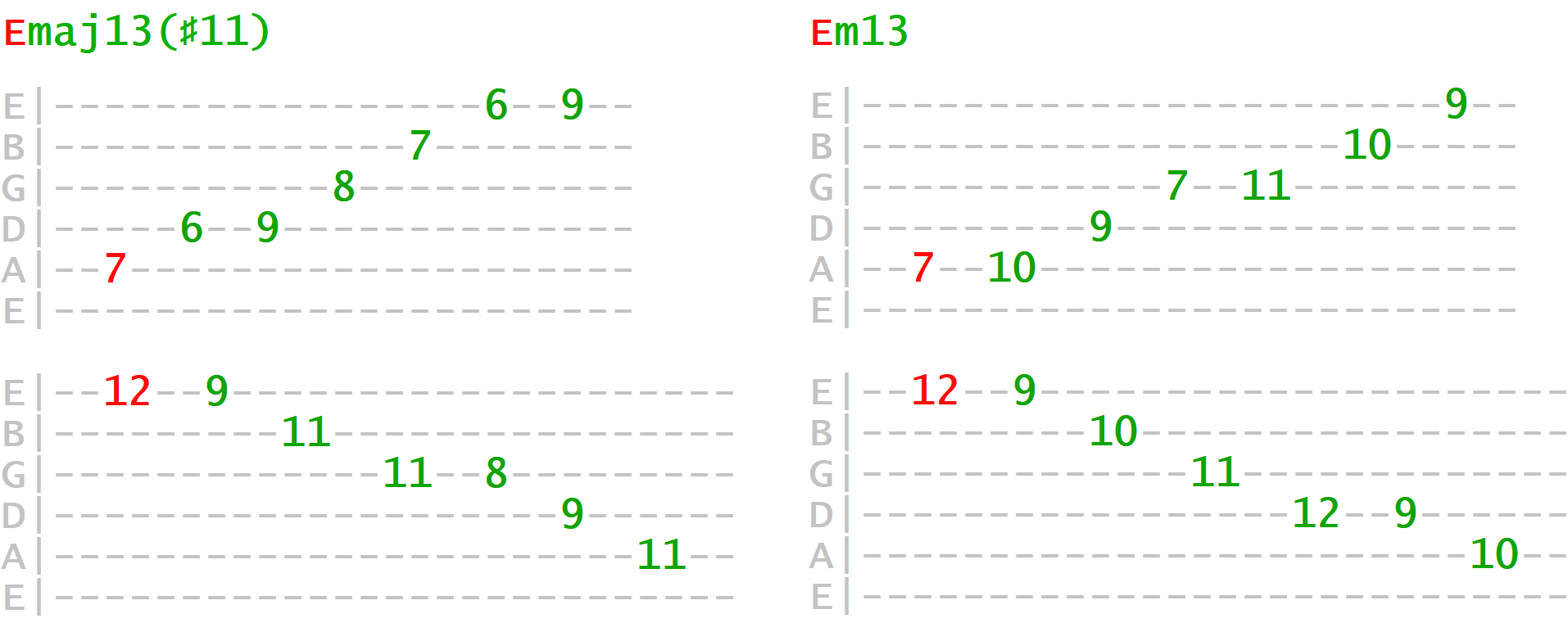

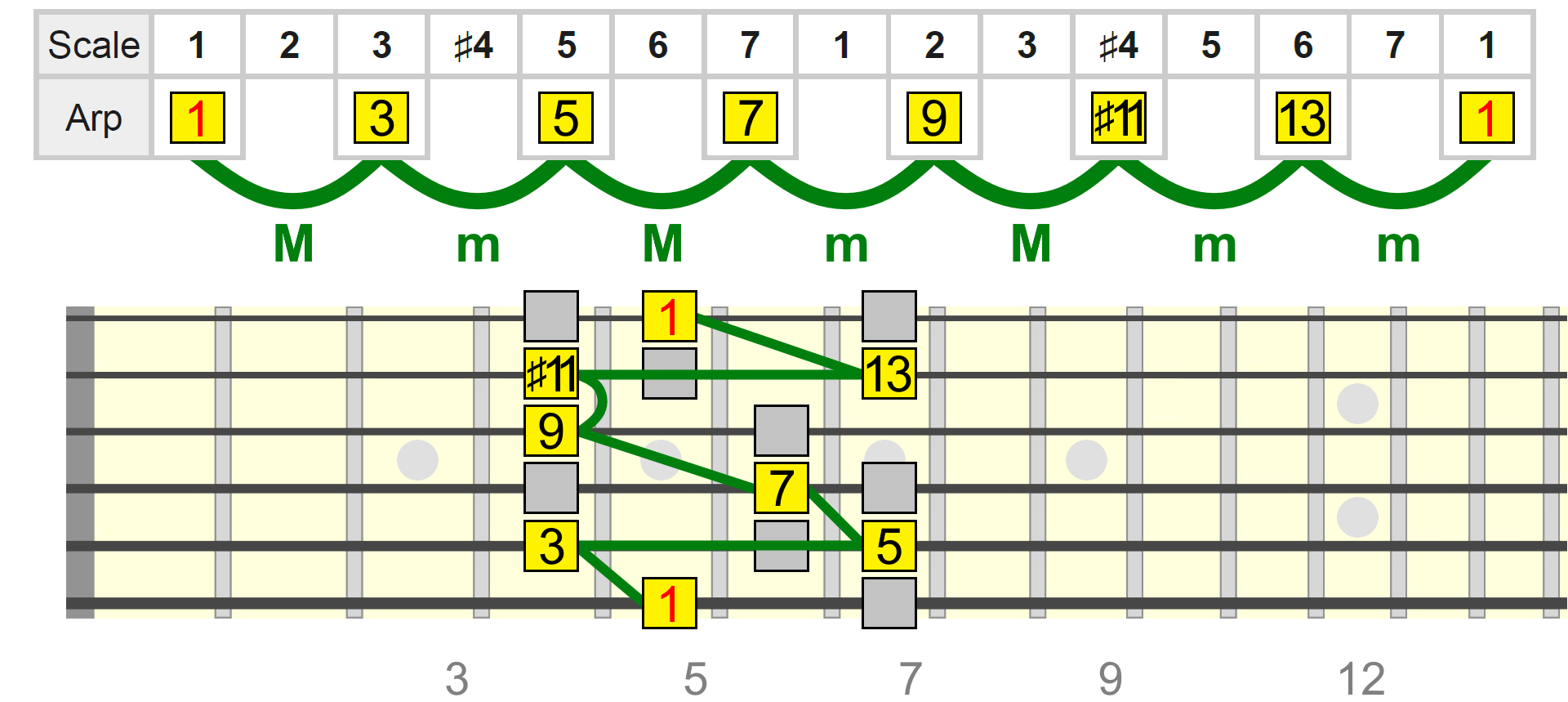

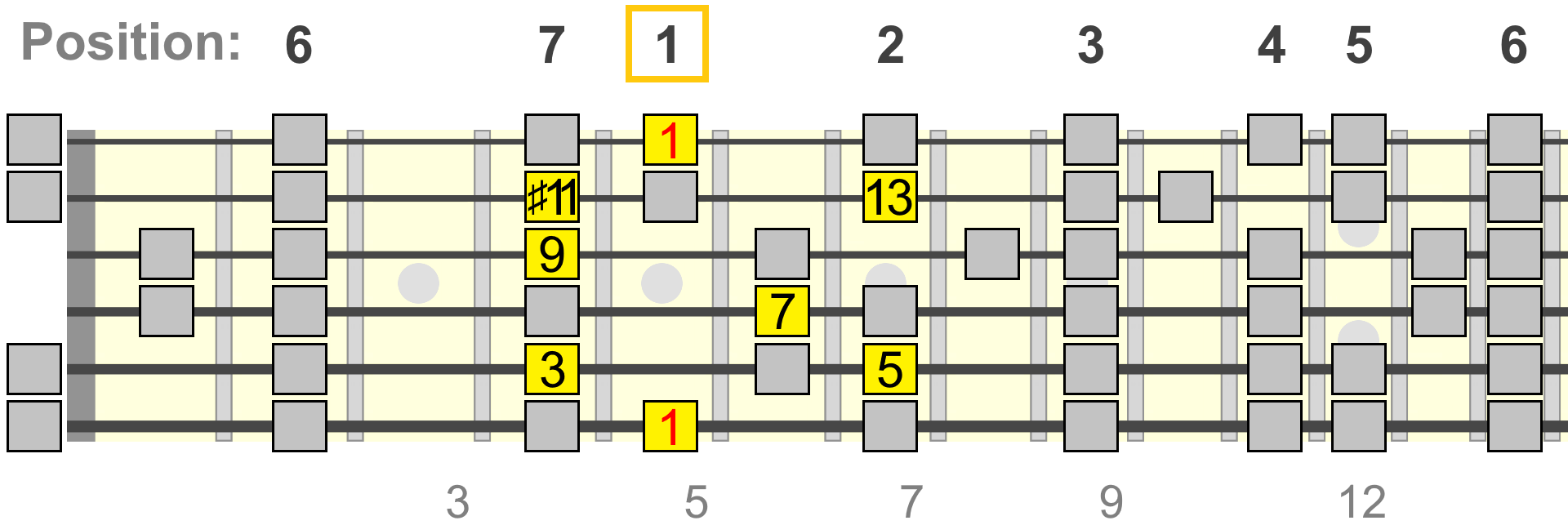

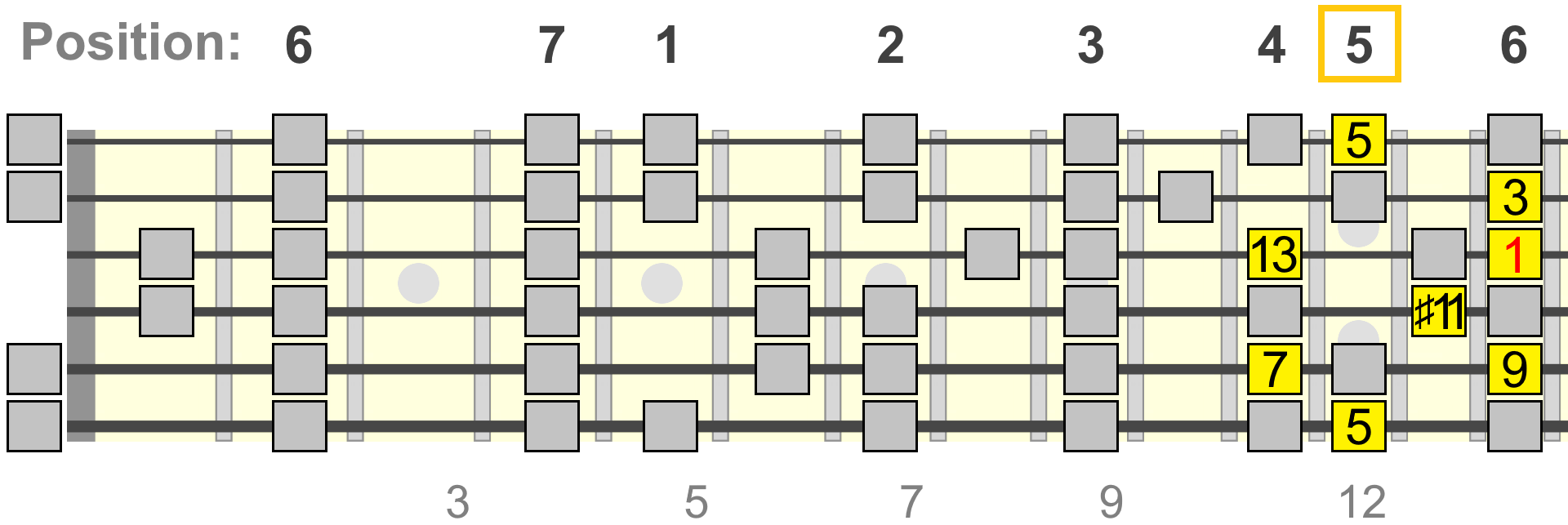

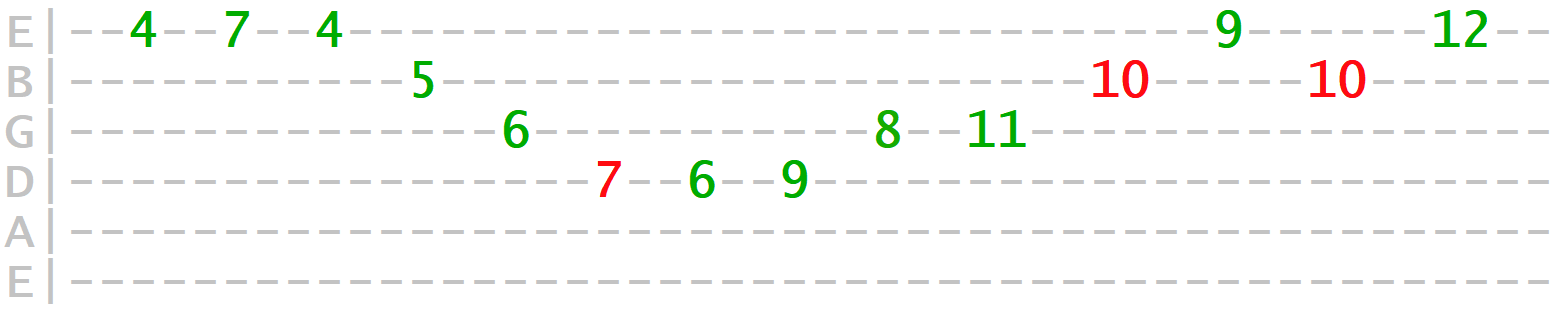

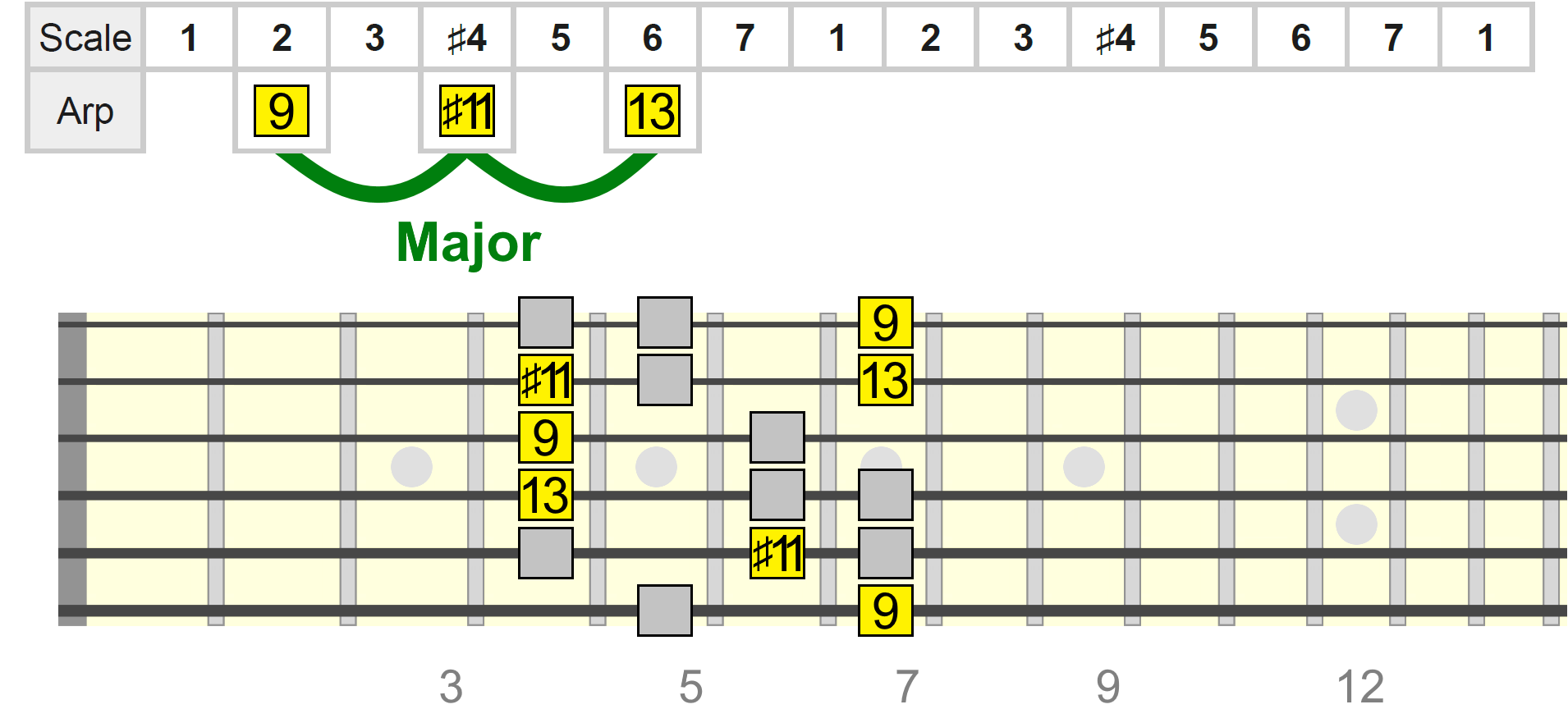

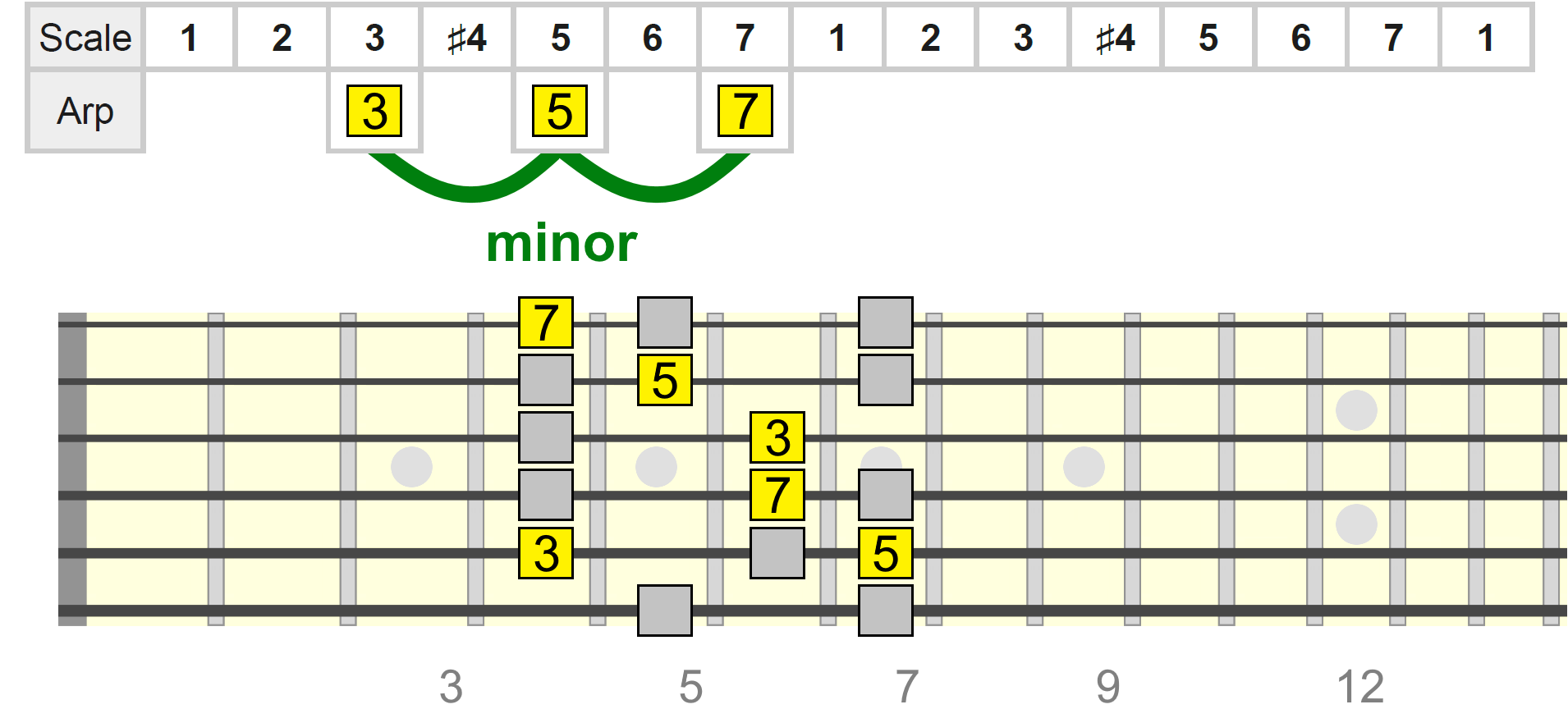

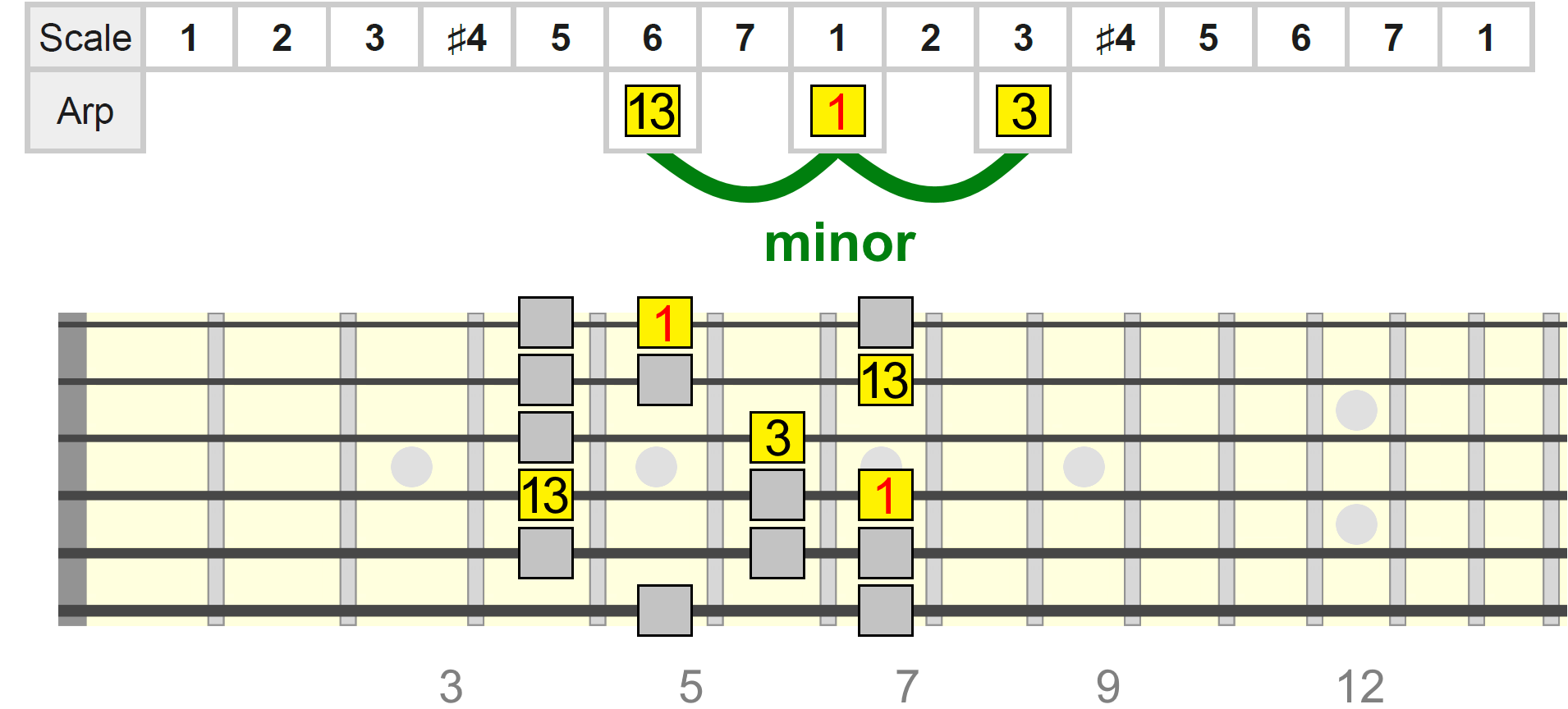

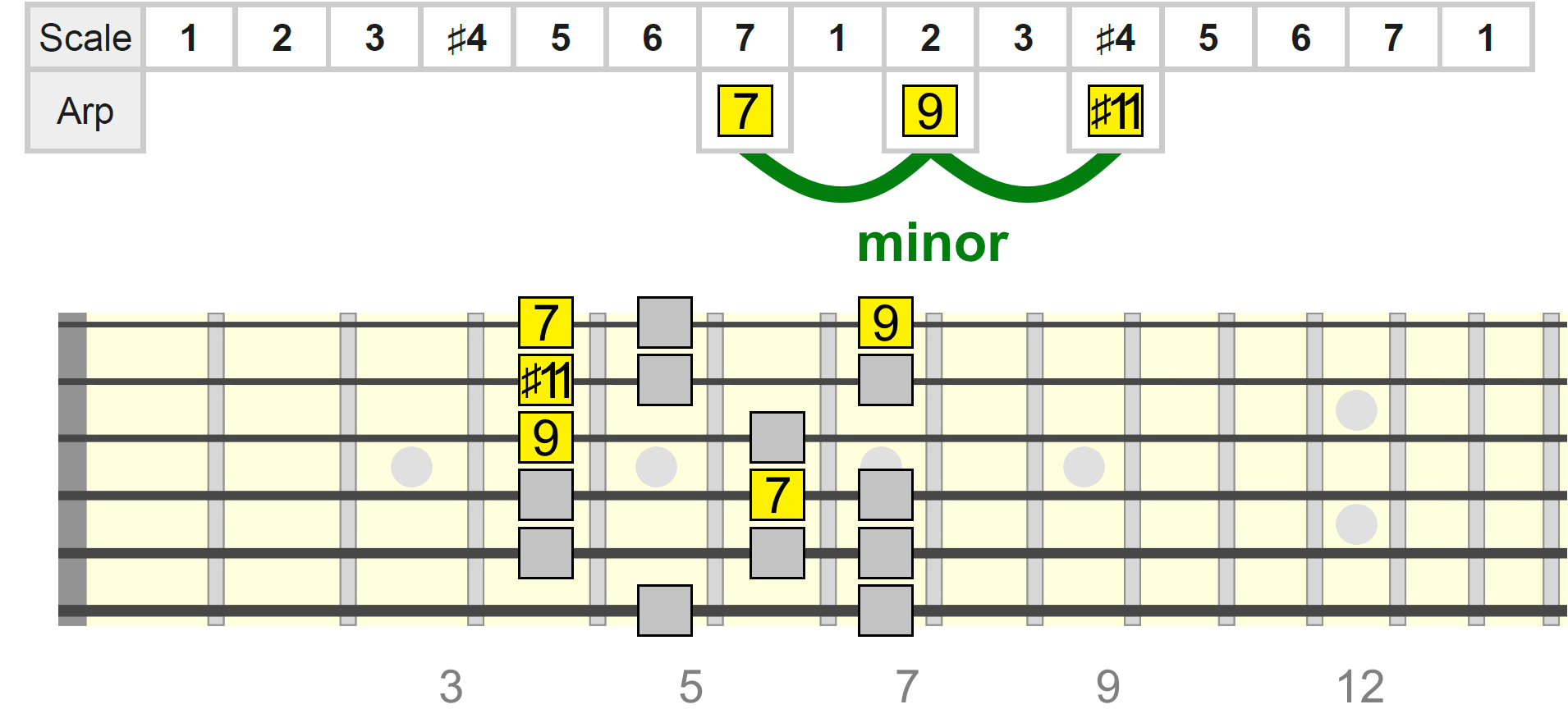

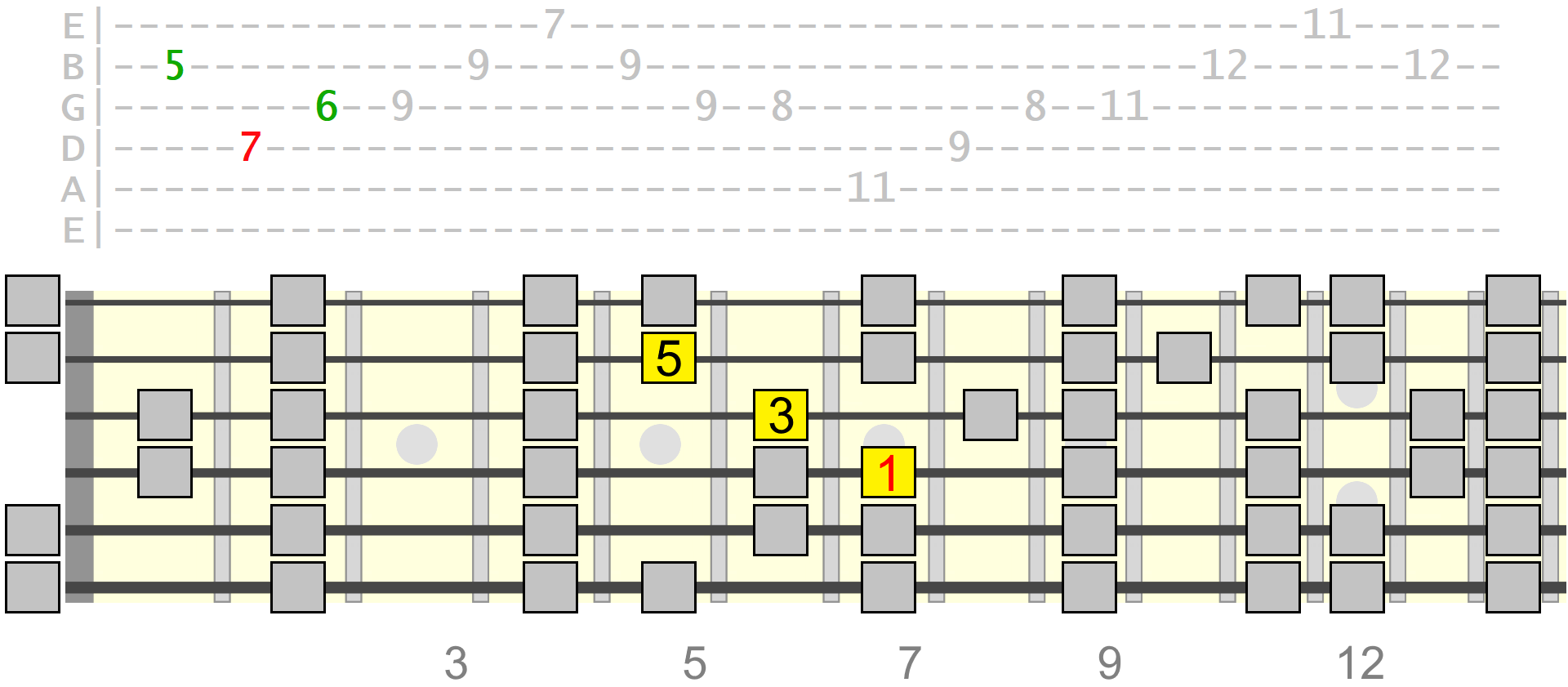

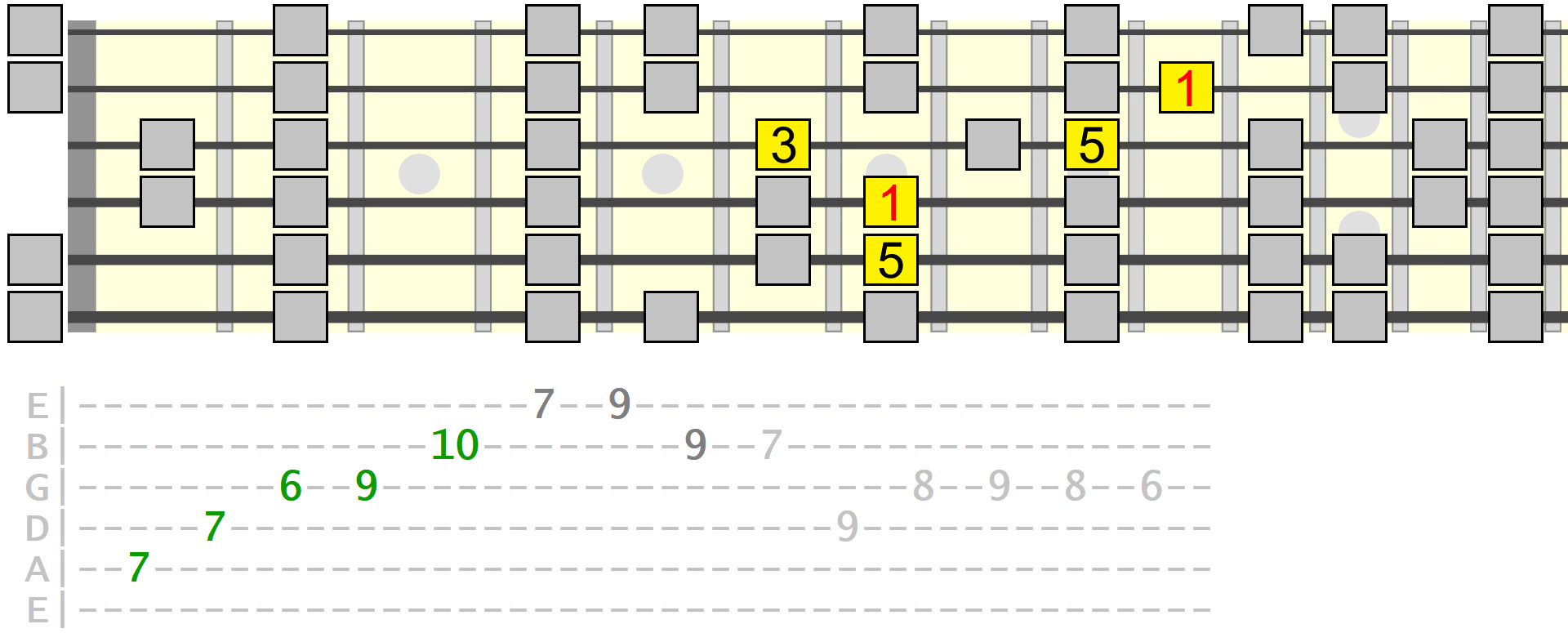

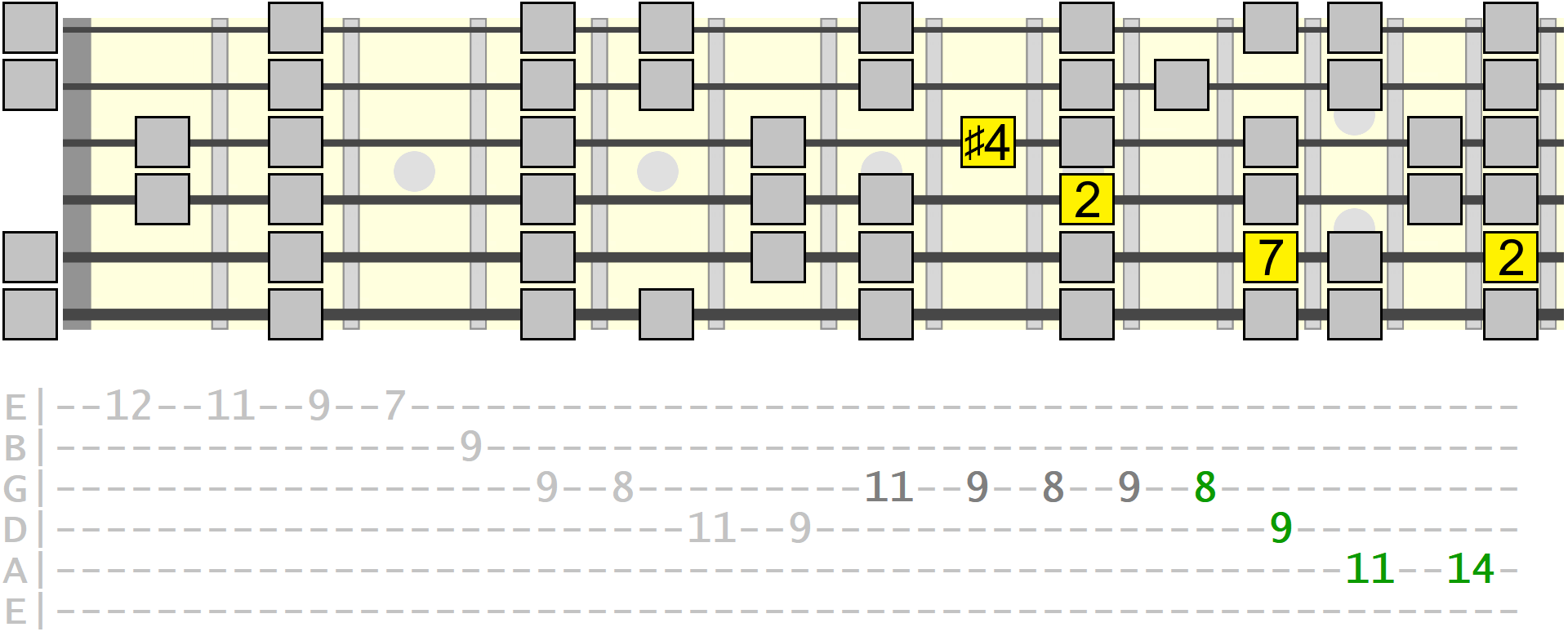

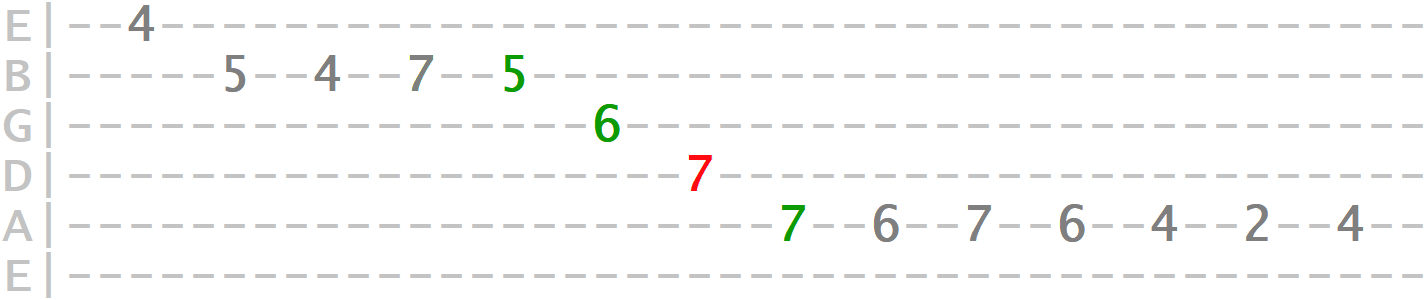

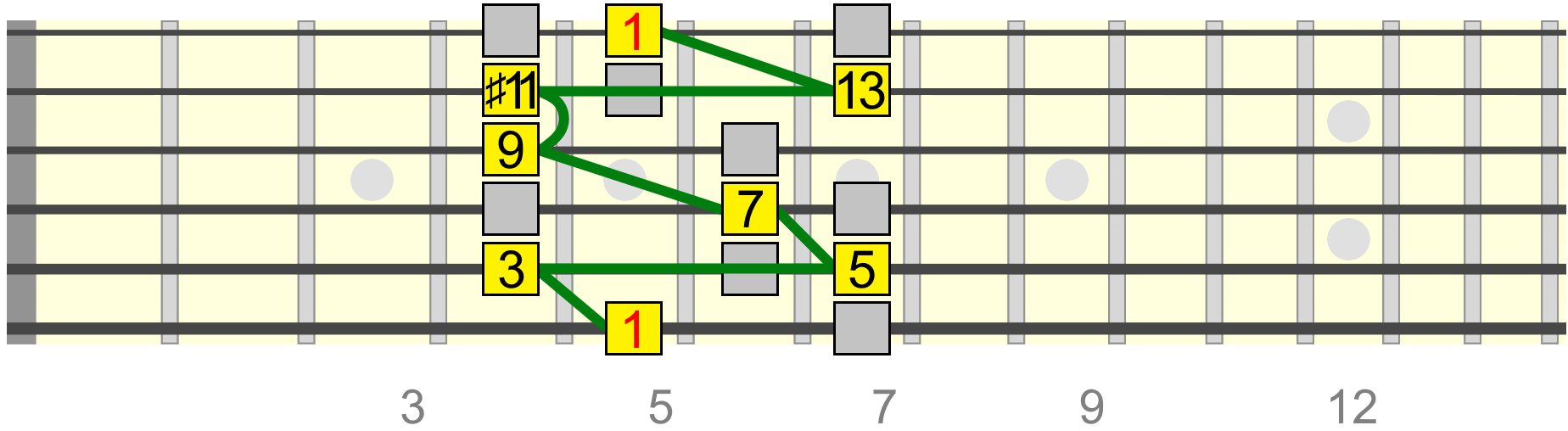

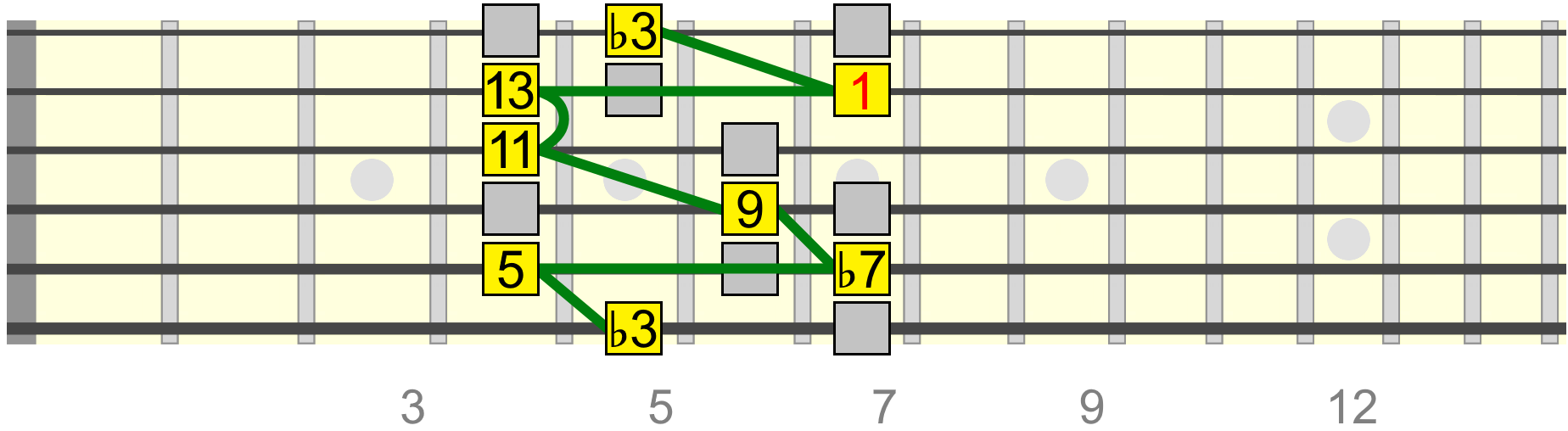

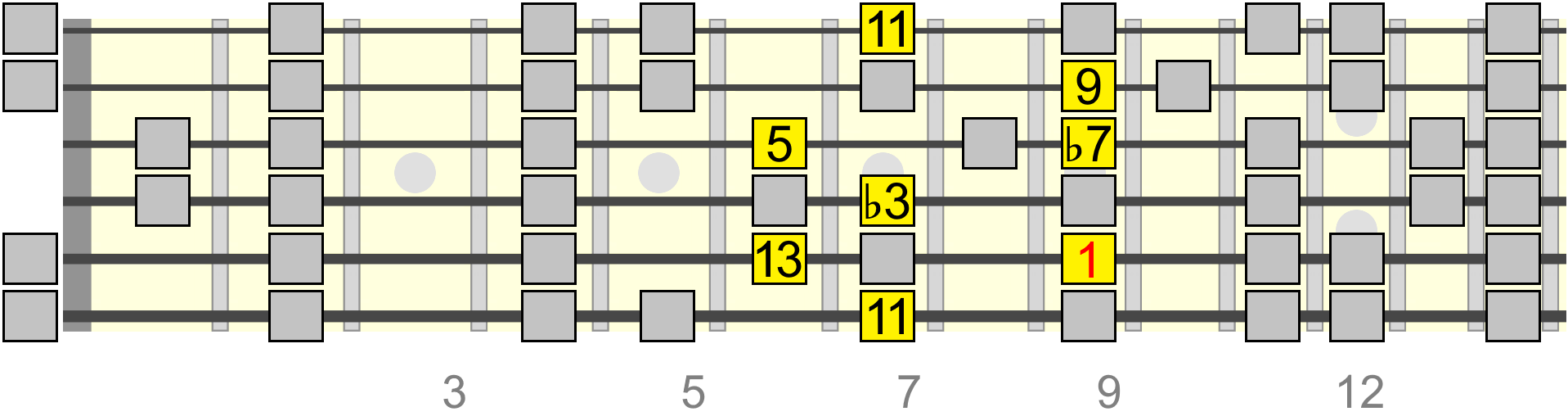

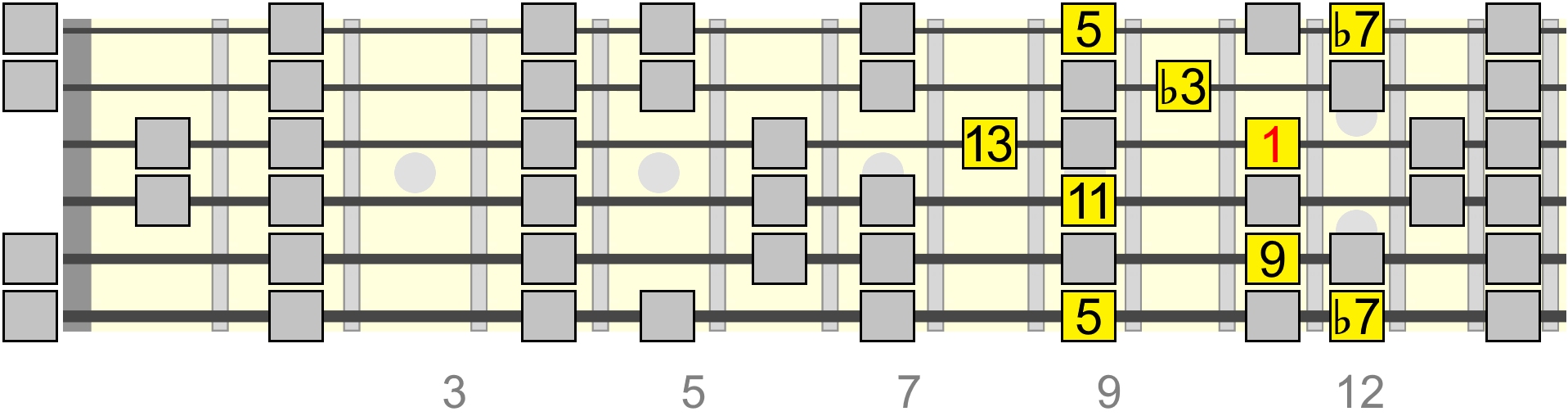

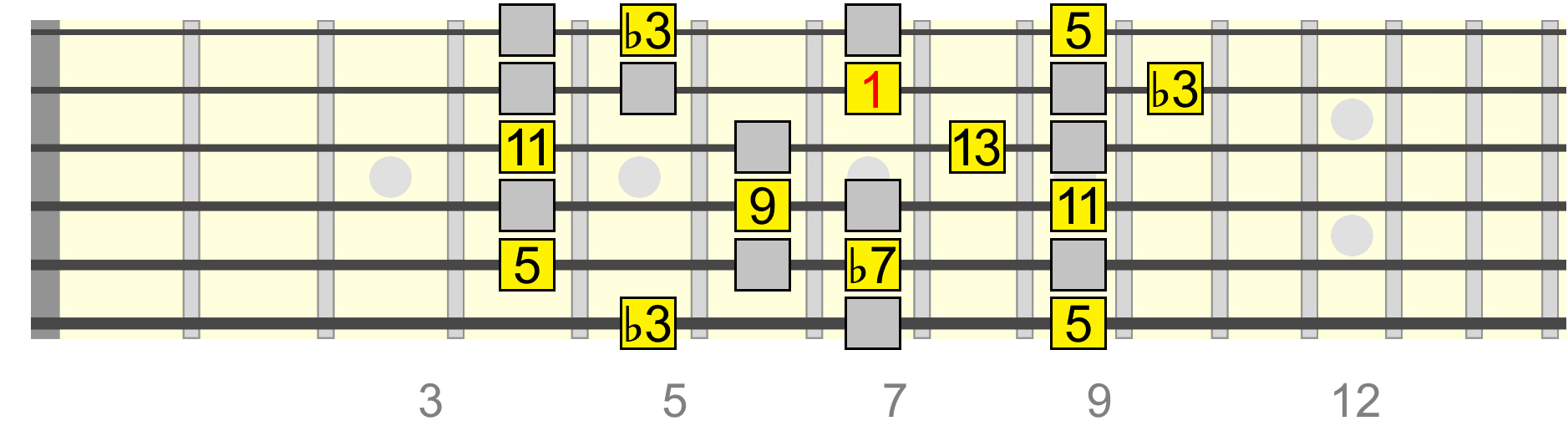

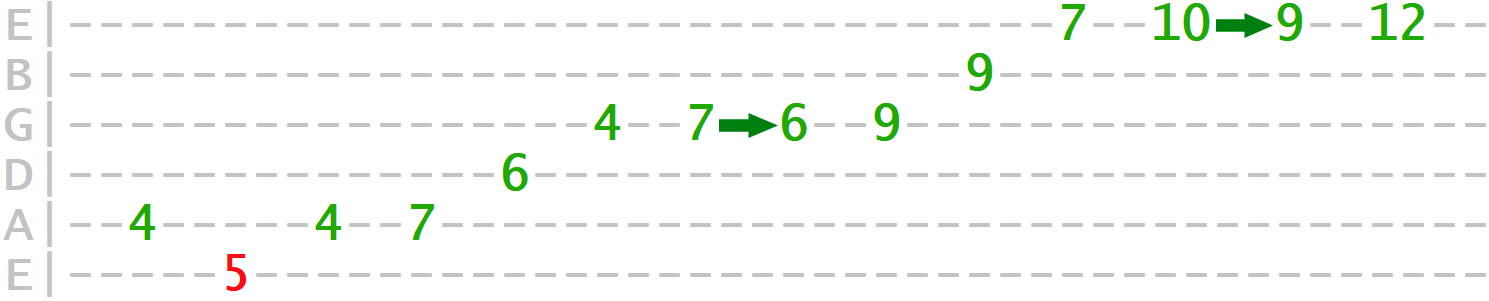

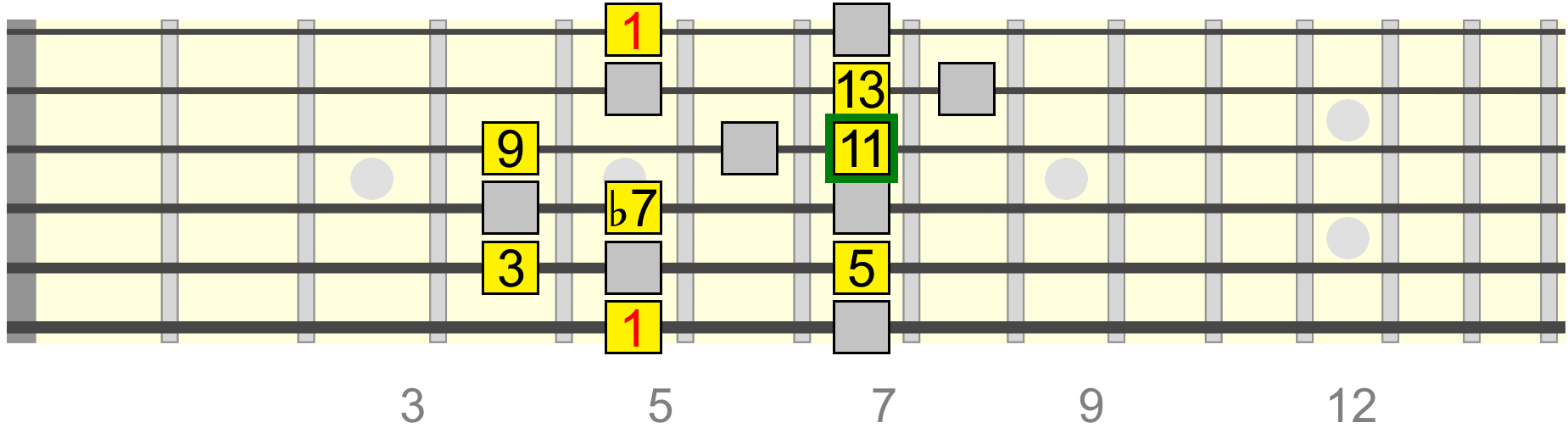

The image here shows how two extended arpeggios (Maj13♯11 and min13) would be stacked, ultimately giving us a seven-tone outline of the chord. Here's one way we could play them on the neck (using the root of E for both)...

They can of course be played as an ascending or descending sequence. And we can begin and end on any tone within that extended sequence.

But there's another way of visualising and approaching arpeggios that helps us to integrate them with our linear or horizontal scale movements and, as a result, give our lead phrases more shape. Those two arpeggios above can also be seen as the vertical expression of a seven-tone scale - namely, Lydian for maj13♯11 and Dorian for min13.

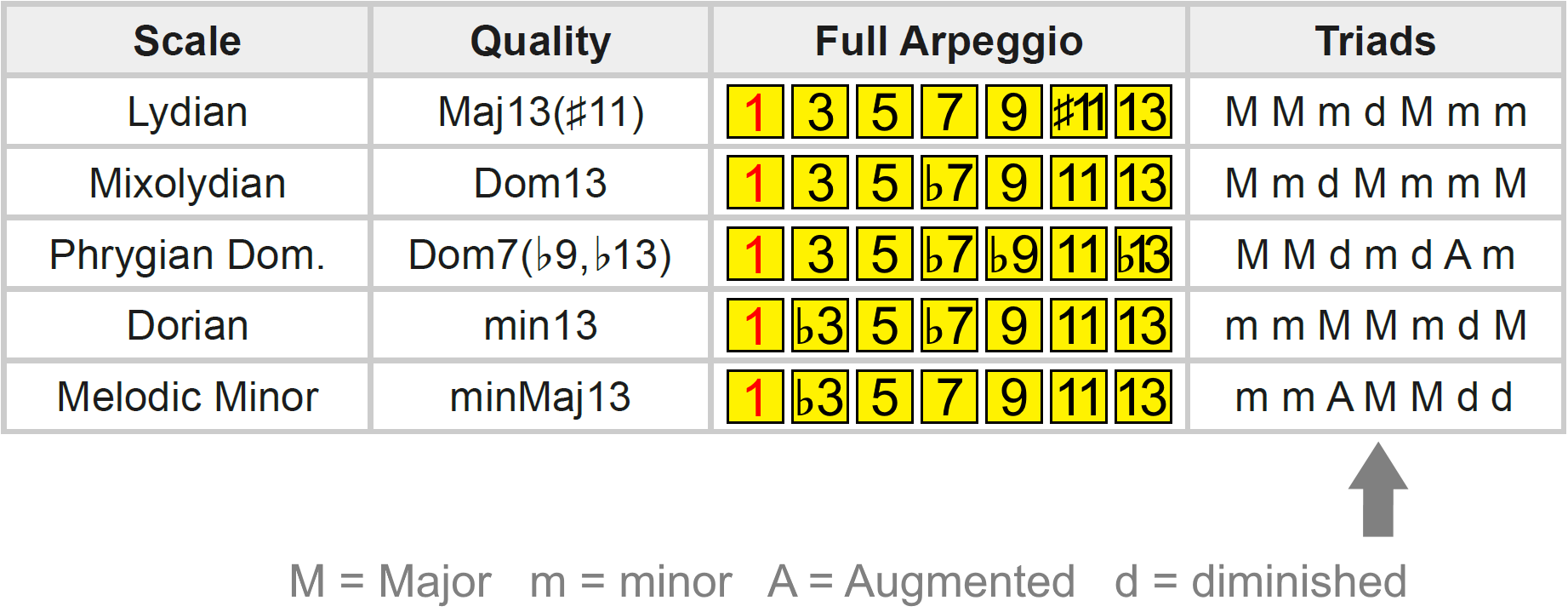

Any seven-tone scale, such as those shown below, can be expressed vertically, as an arpeggio, which outlines the scale's native chord quality. And these full, seven-tone arpeggios can be fragmented into simpler arpeggios, such as triads, for more accessible phrasing options.

Forming The Arpeggio - Stacking 3rds

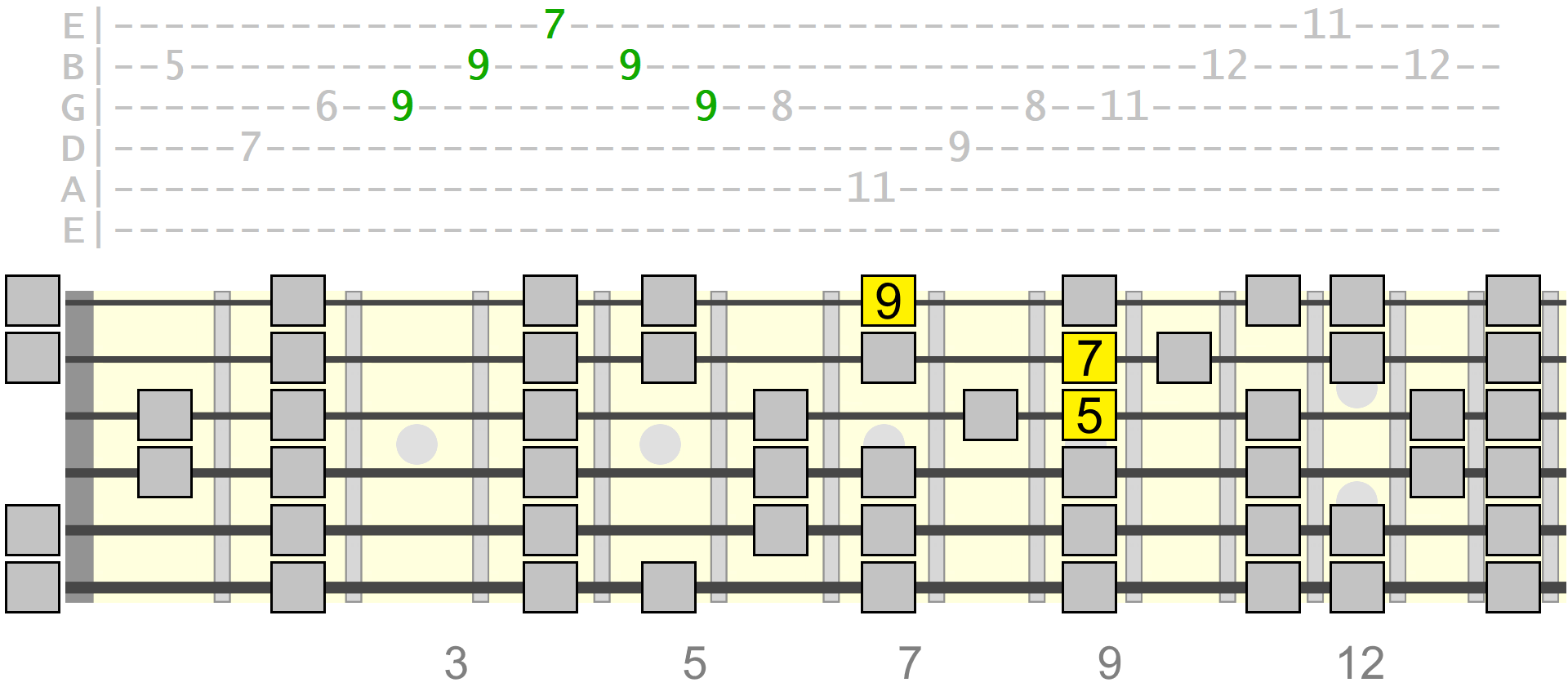

To form the basis of our vertical expression of a scale, we can use a technique known as stacking 3rds or jumping in 3rds. This is the same as skipping every other tone in the scale's natural sequence.

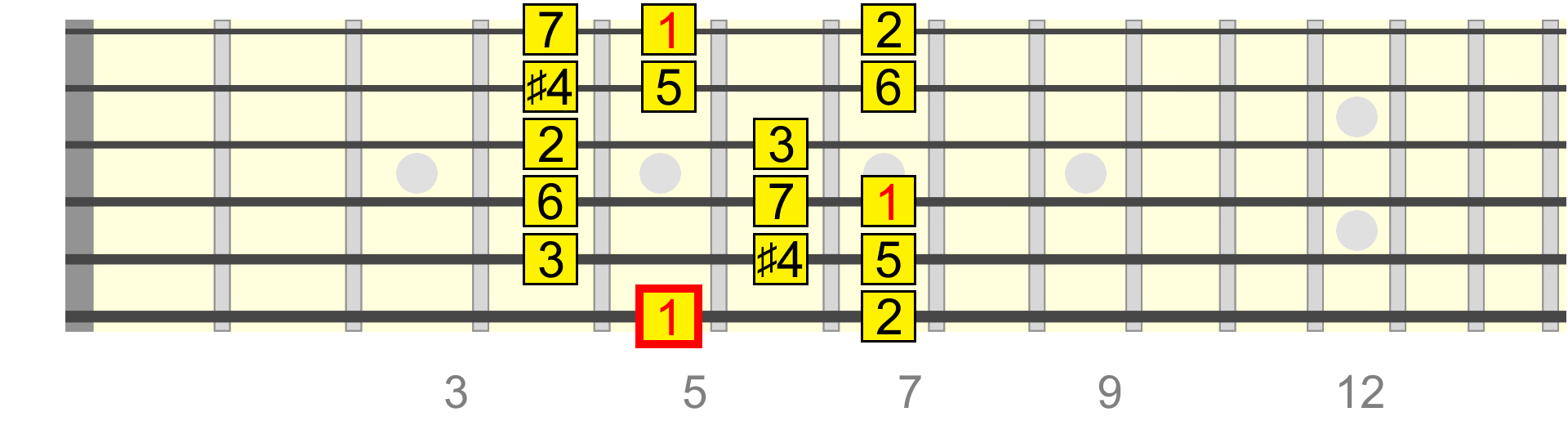

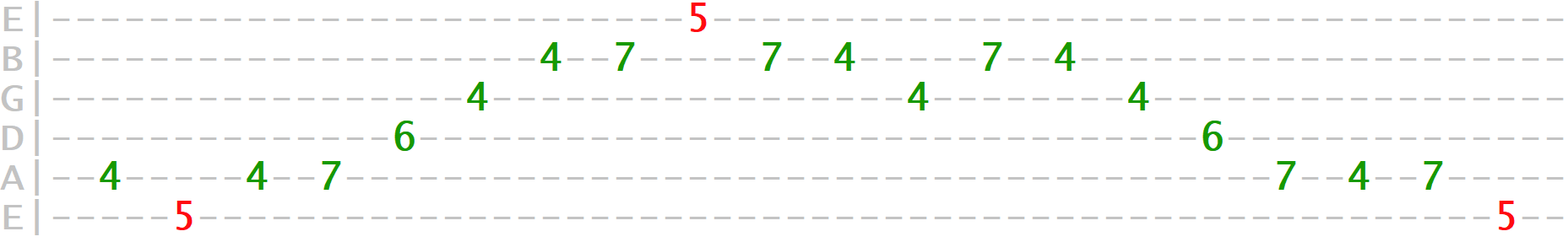

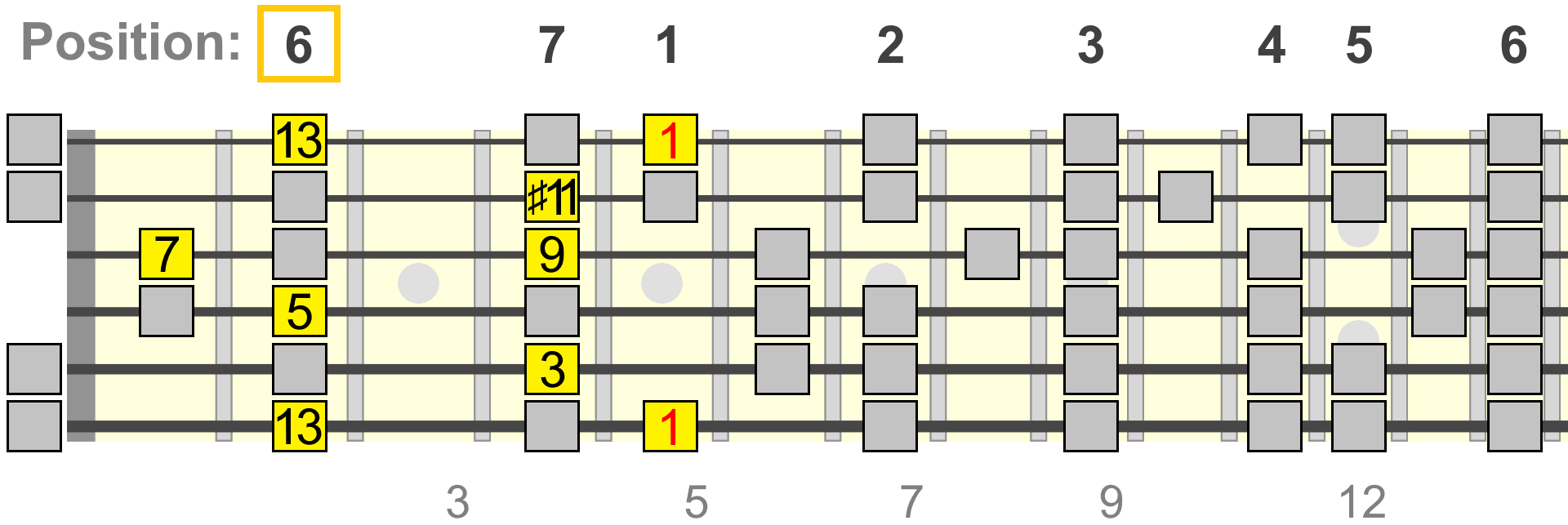

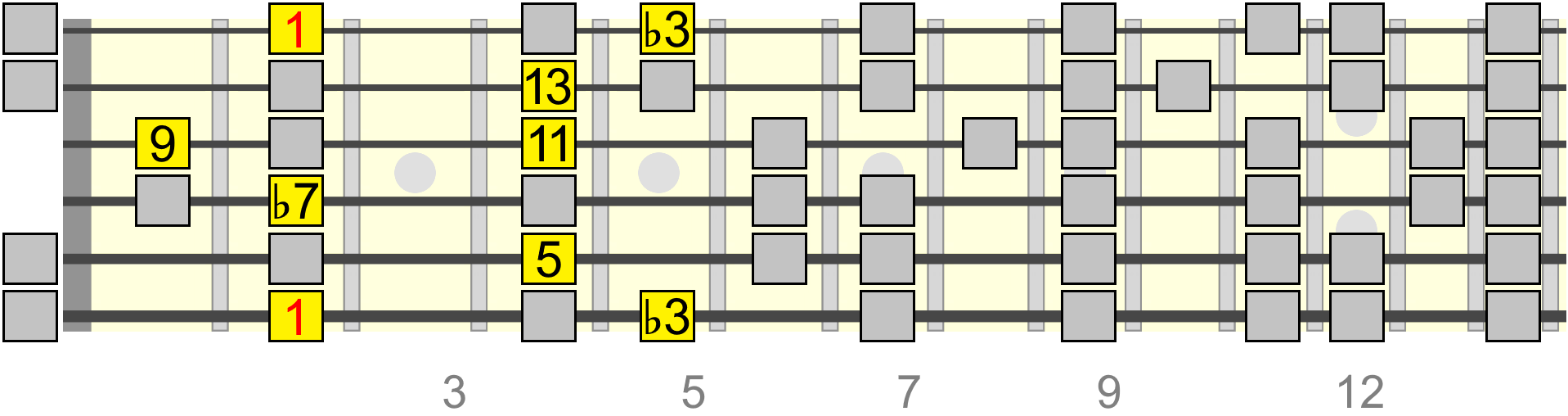

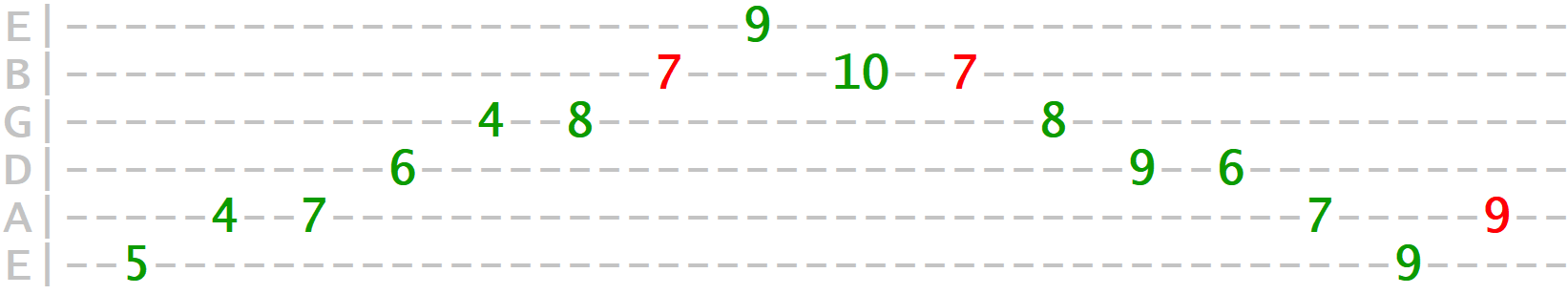

Take Lydian, a commonly used major scale, as an example, though remember that the process we're about to follow applies to any seven tone scale. Here we have a condensed box pattern starting on A at the 5th fret, which marks the 1st degree of our A Lydian scale...

We're now going to move through the scale in intervals of a 3rd, which is the same as skipping a degree from one tone to the next. Depending on how the interval falls in the sequence, we'll either be moving in a major 3rd (M) or minor 3rd (m)...

Let's connect these 3rds up into a sequence...

Tip: Use a chord track generator to create a backing for your practice and ideas throughout this lesson. Simply select your chord(s), tempo, beat (if desired) and then explore the patterns provided in this lesson.

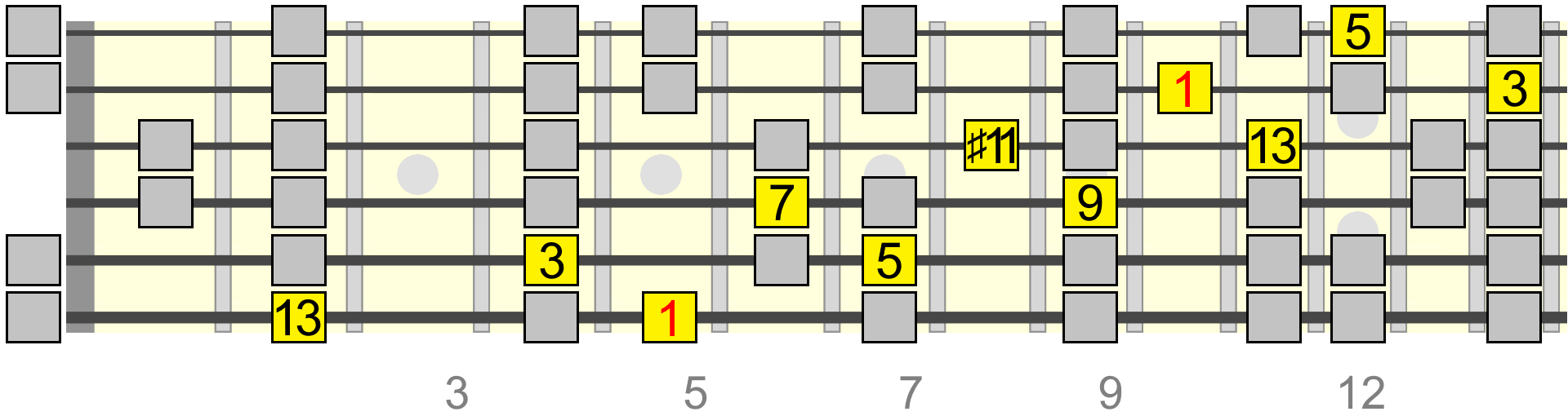

We've now played through all seven tones of the scale, but vertically, in arpeggio form. Incidentally, this complete seven tone arpeggio gives us the native extended chord quality of this particular scale - major 13th, augmented 11th (or Amaj13♯11 in this case). A major triad, with a major 7th and a 9th, ♯11th and 13th as extensions.

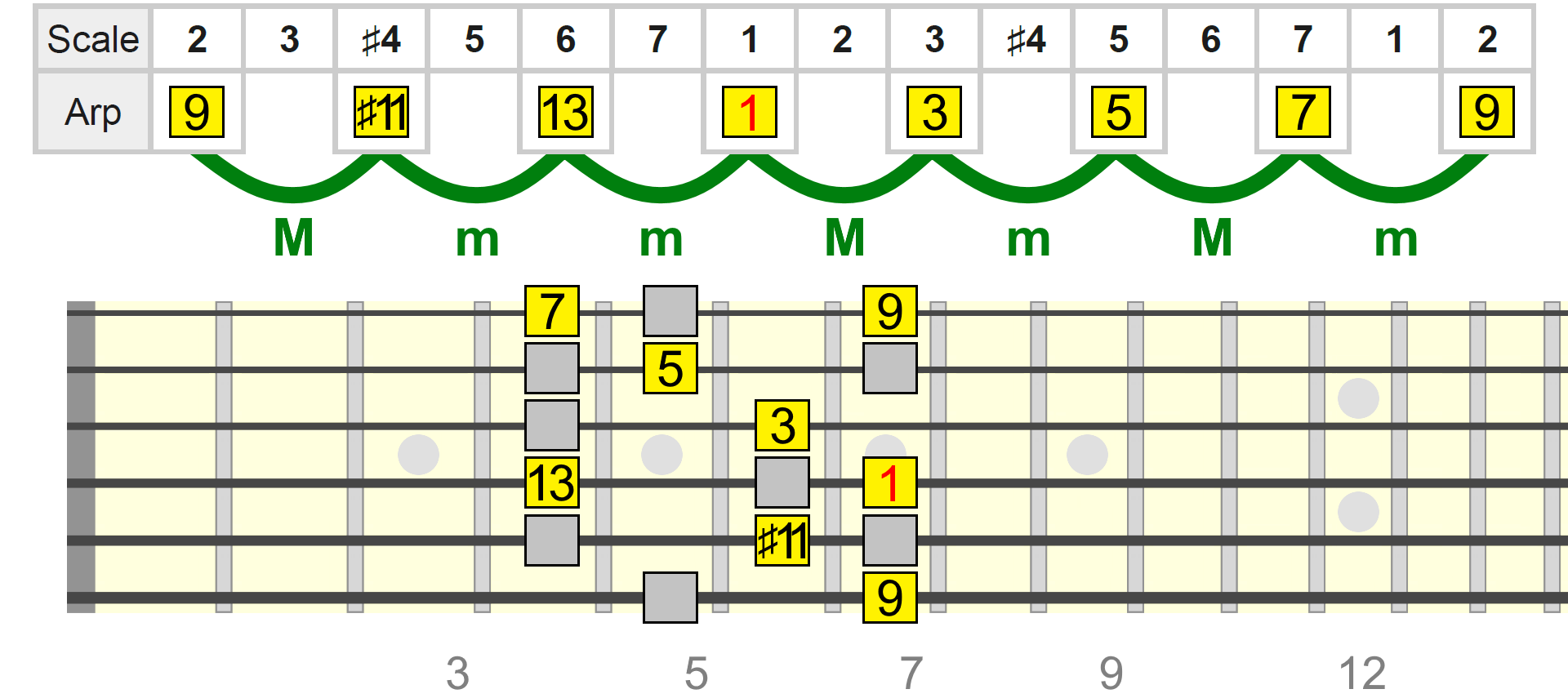

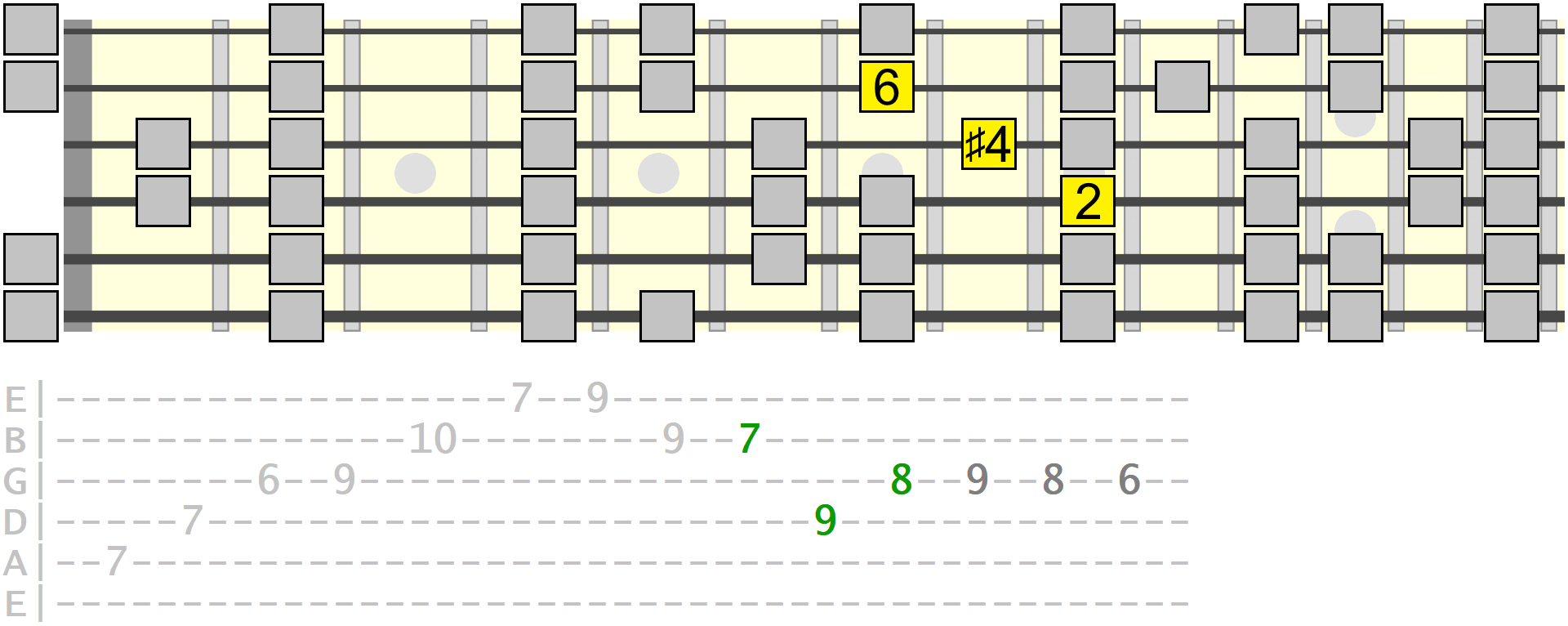

We could also stack in 3rds from the 2nd degree, or starting on the 9th of our arpeggio, the lowest of which we initially skipped over in the first sequence...

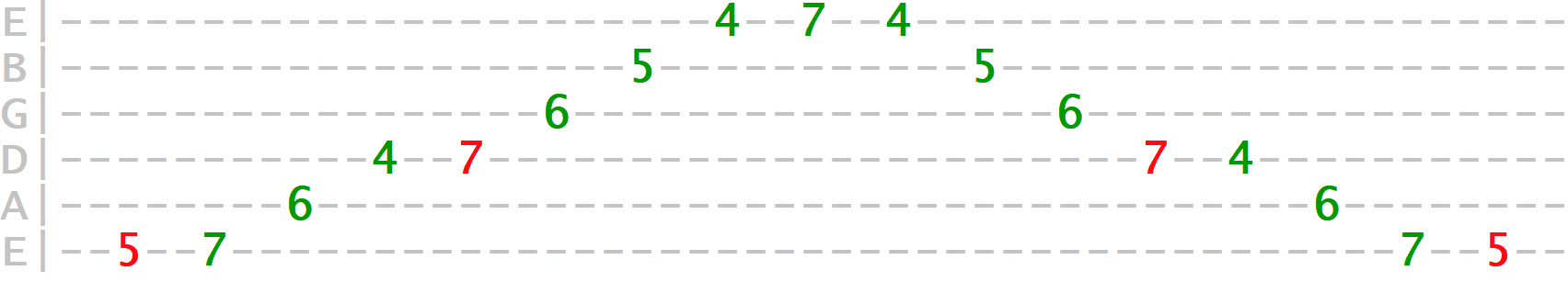

While this essentially gives us the same seven-tone arpeggio as before, it does offer us higher and lower voicings of certain tones. Here we start on the scale's tonic before moving into the arpeggio from the 2nd degree...

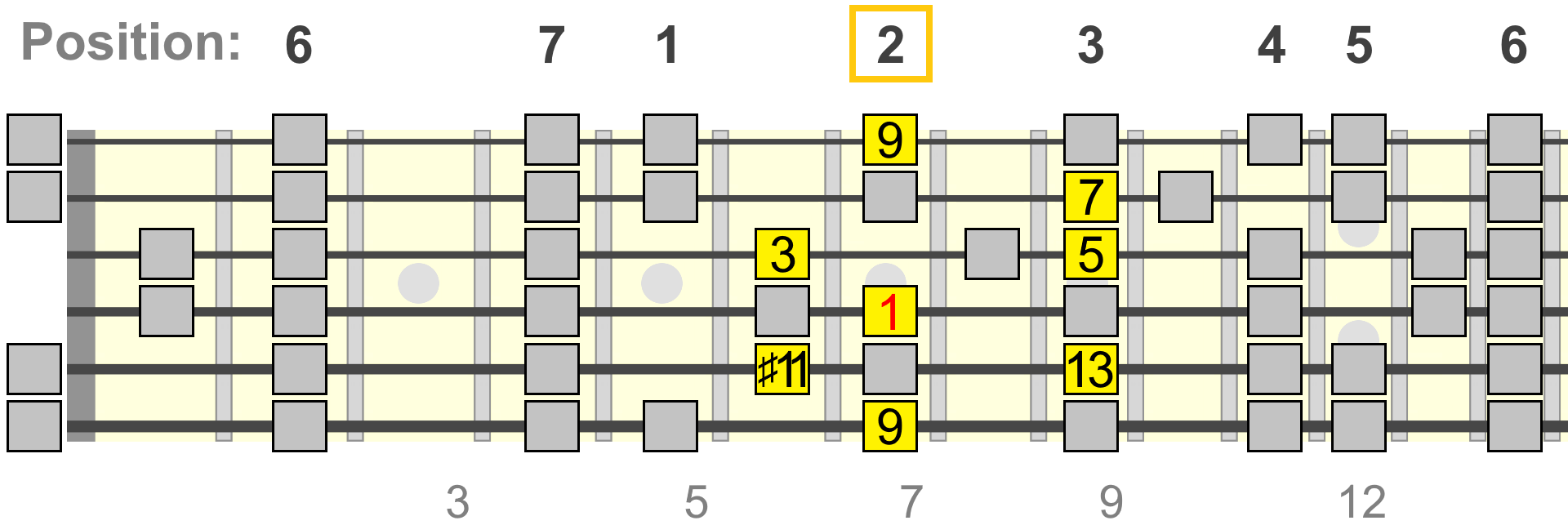

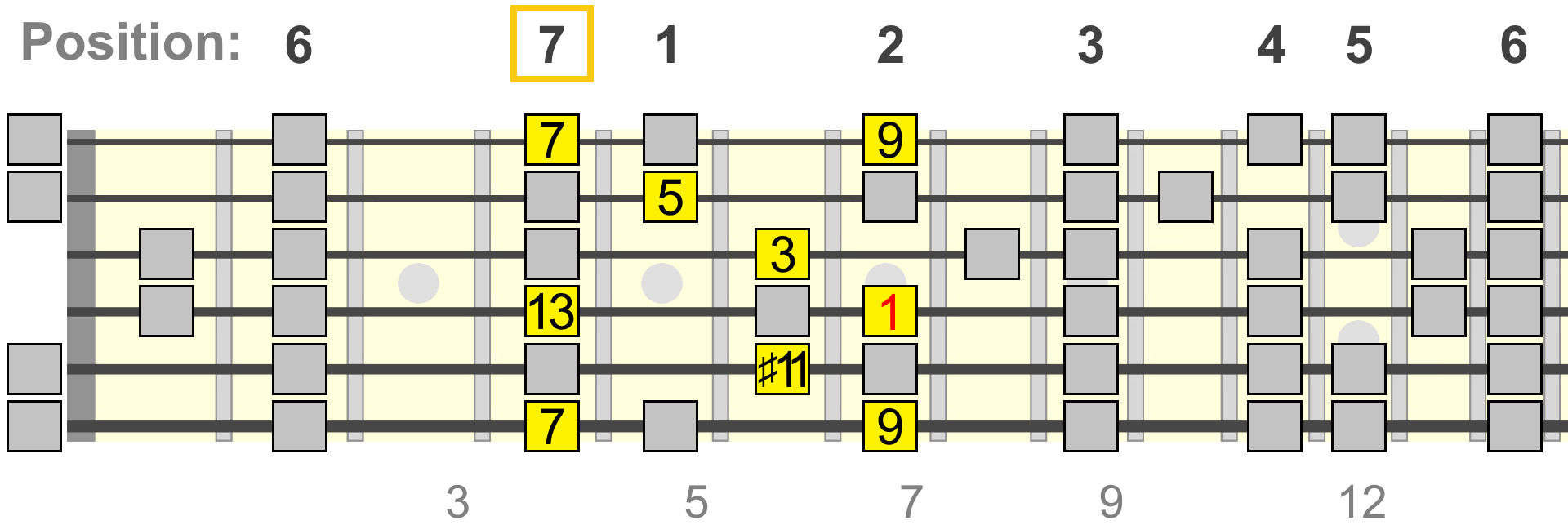

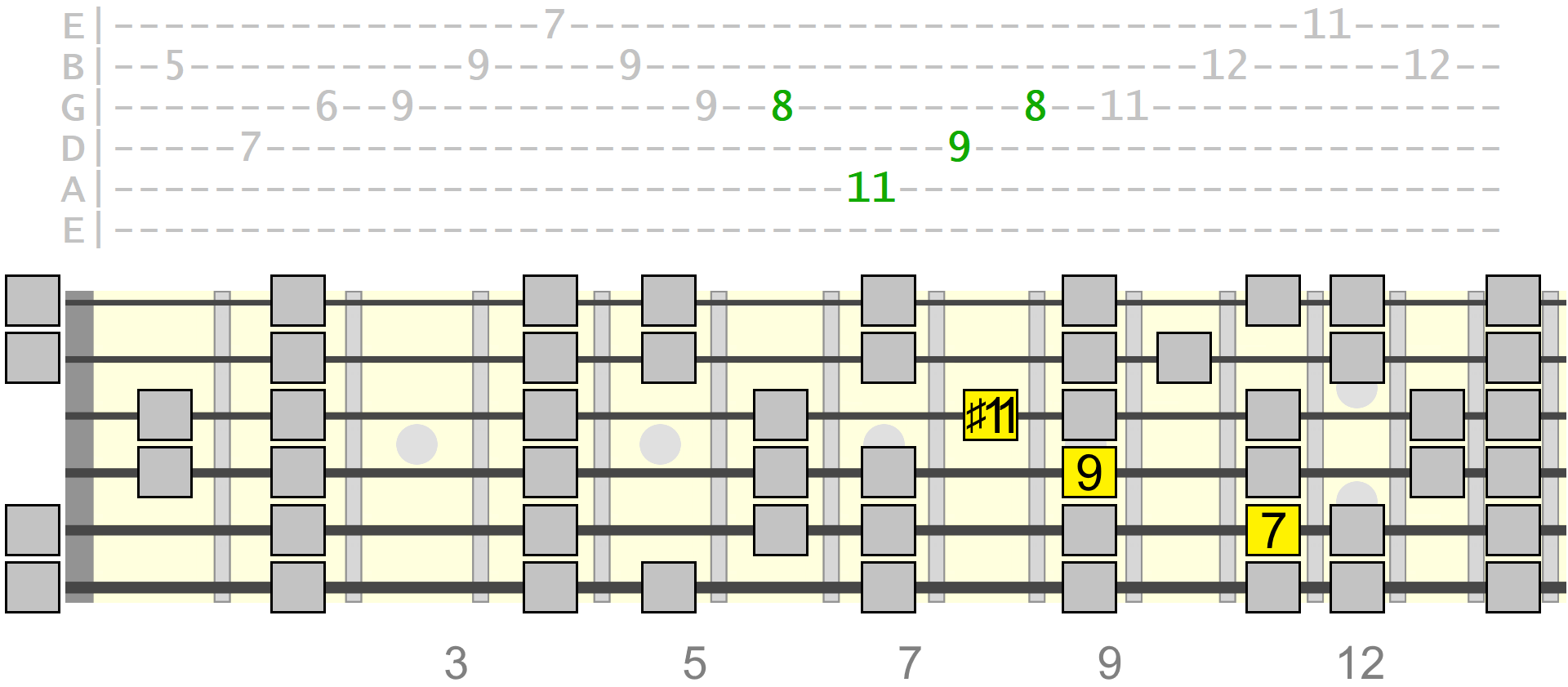

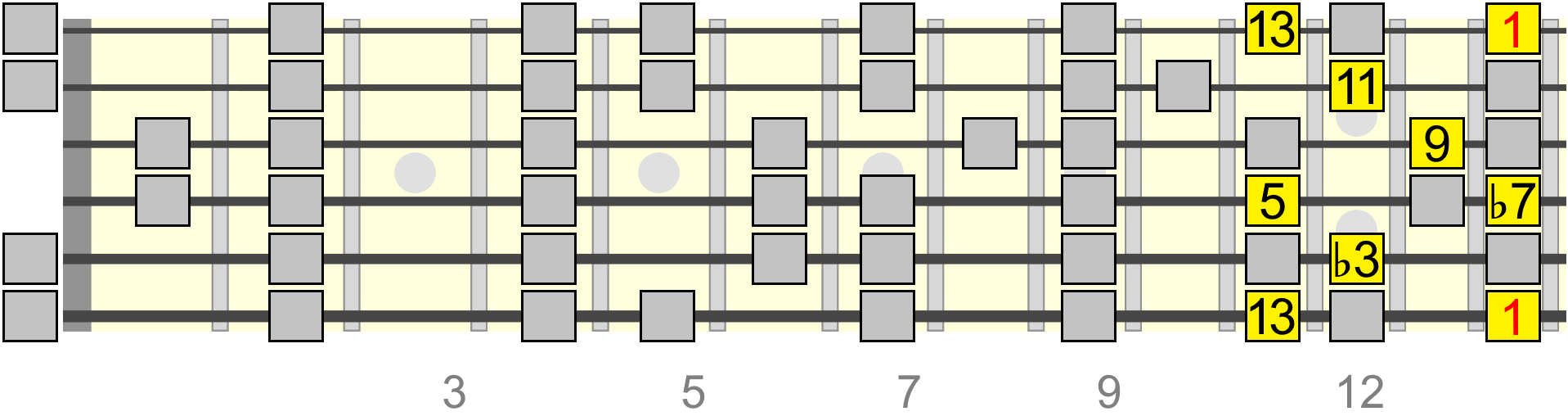

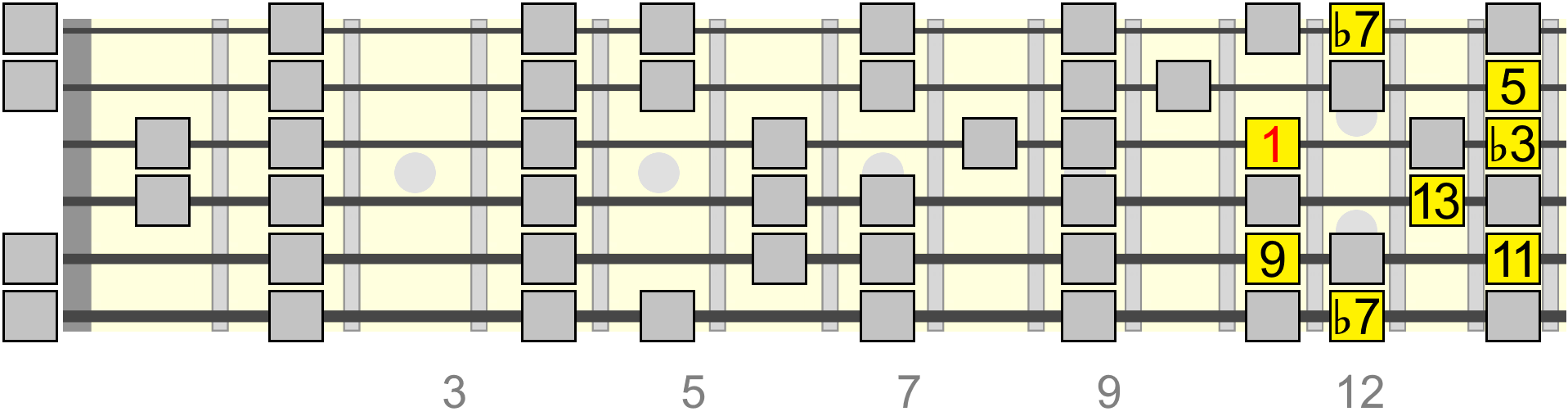

In fact, we could begin stacking 3rds on any scale degree and it would simply be a continuation of the full arpeggio stack. This leads us to our next exercise - connecting the scale's arpeggio to other box patterns/positions up and down the neck, using the same 3rd jumping technique...

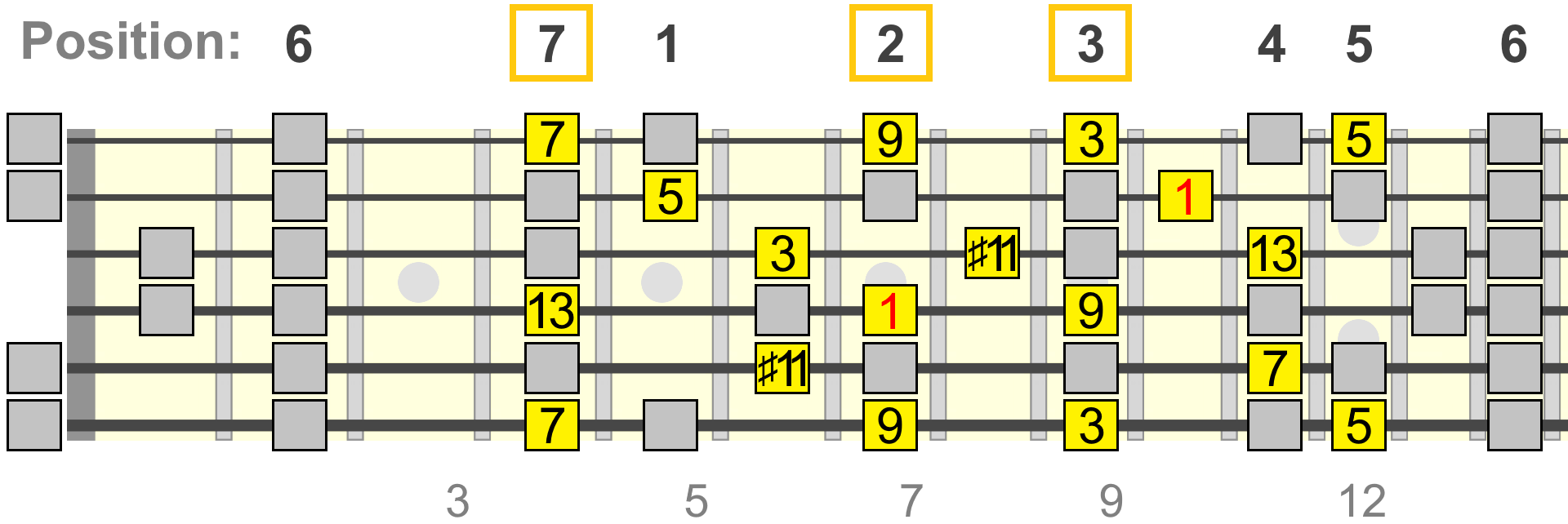

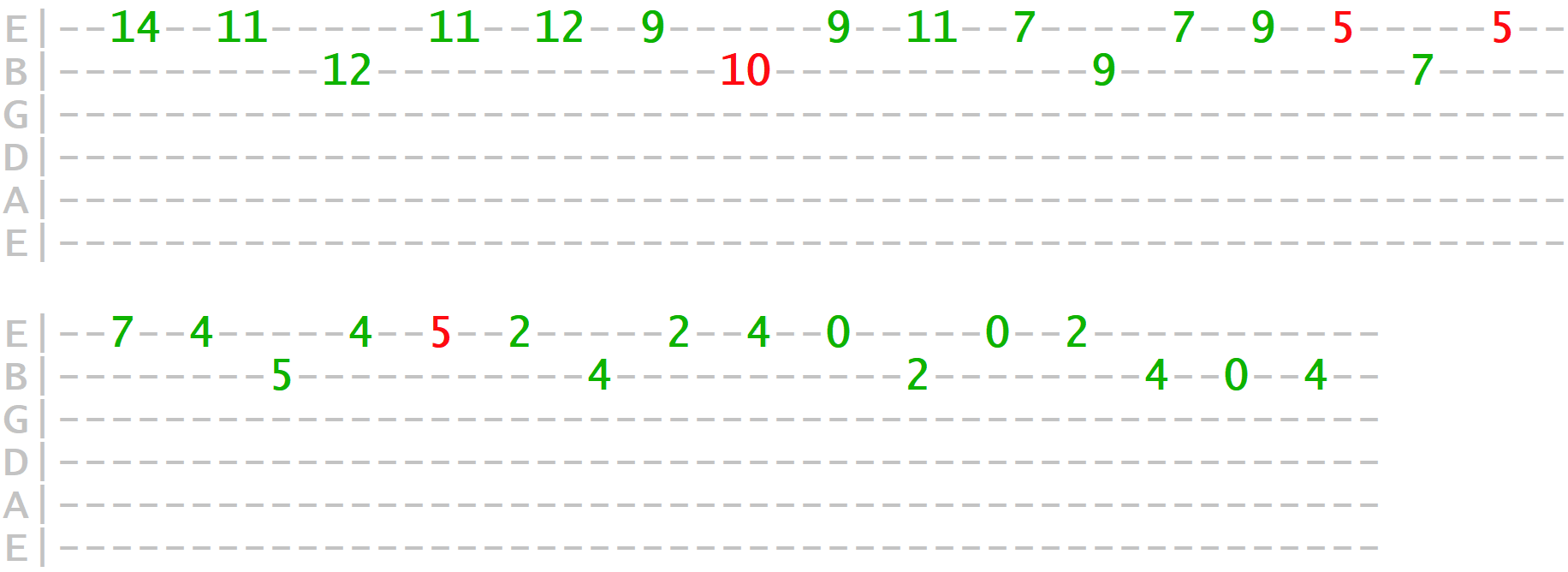

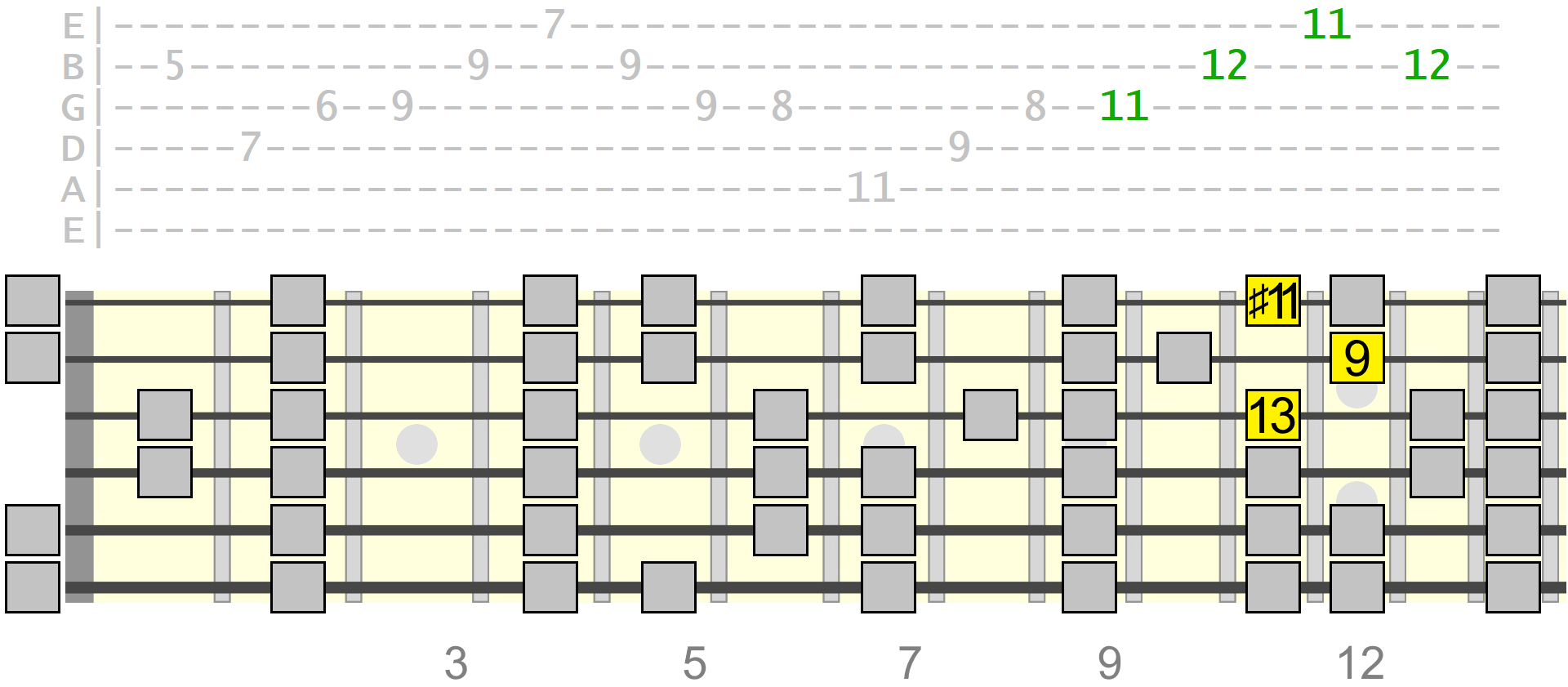

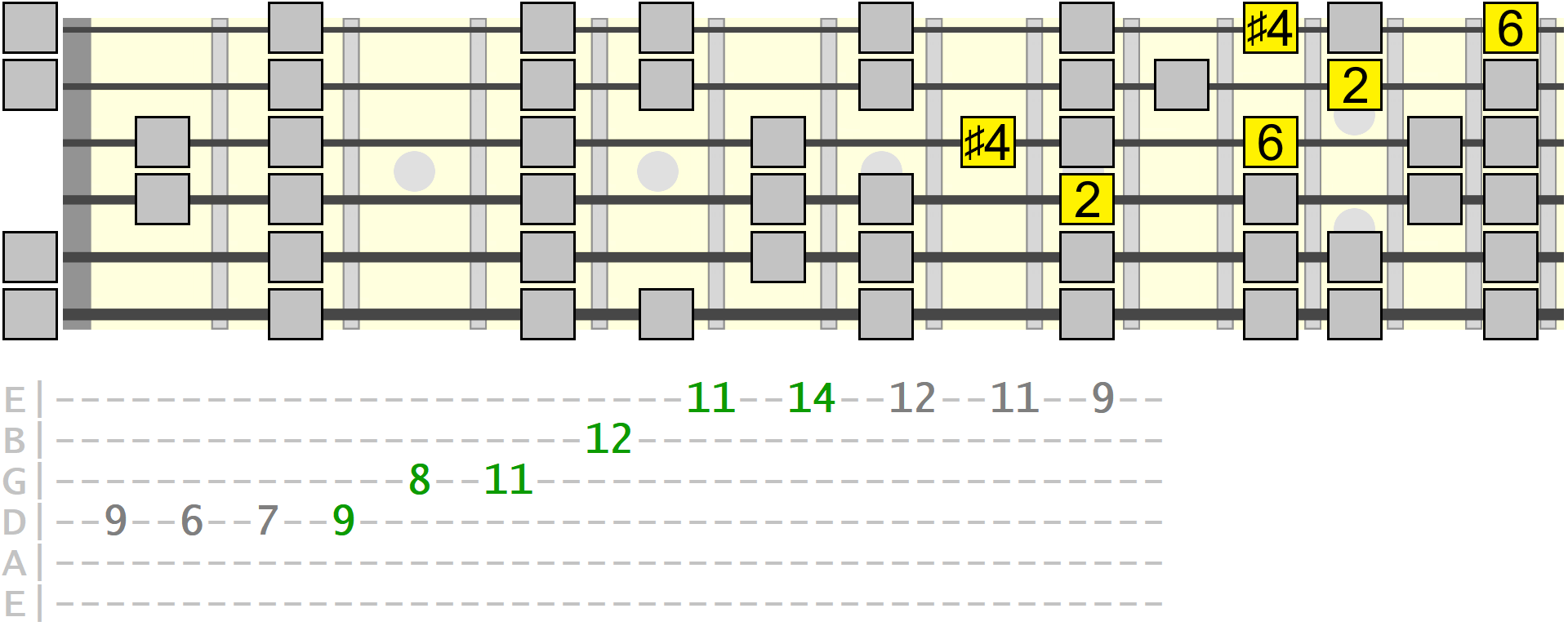

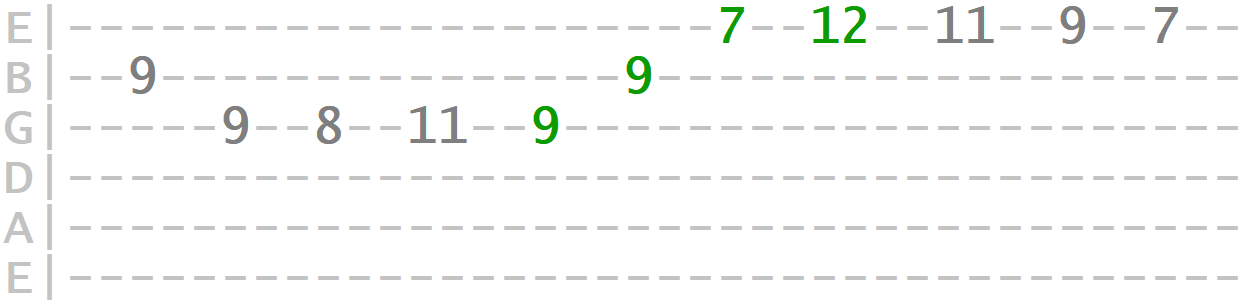

Gradually, we'll start to flow through these patterns more intuitively and freely, just as we would with regular scale movements. Here's an example of using these box positions to connect up different areas of the neck with the scale's arpeggio...

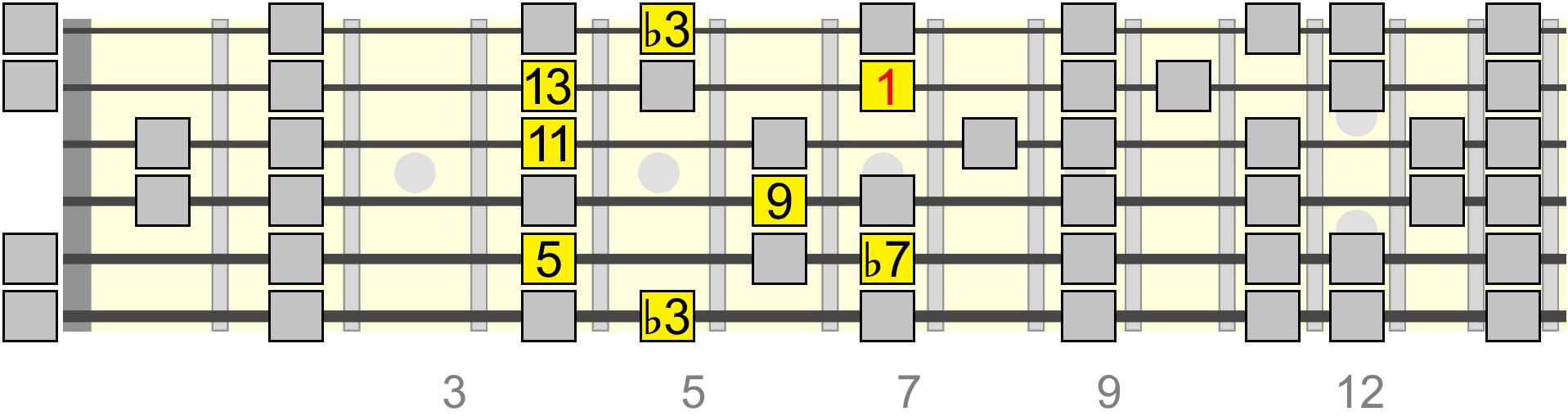

This merging of patterns will inevitably lead us towards creating new patterns that span a wider neck area, such as this one...

Tip: You don't have to play an arpeggio in strict ascending or descending sequence. You can "stagger" the sequence by stepping back and using repetition occasionally. You can also skip tones to create interesting variations on the sequence. In other words, arpeggios don't have to be played in a straight hierarchical order to sound musical.

But the key aim right now is that we can start a scale's arpeggio on different degrees and in different neck positions, visually superimposing those stacked 3rd arpeggio patterns on to any scale pattern.

This is the basis of creating a vertical expression of the scale at hand. And don't worry, we won't have to learn a completely new arpeggio pattern for every single scale, since Lydian shares the same pattern as six other diatonic scales, or the modes of the major scale, which we can re-use over other chords in a key. More on that later.

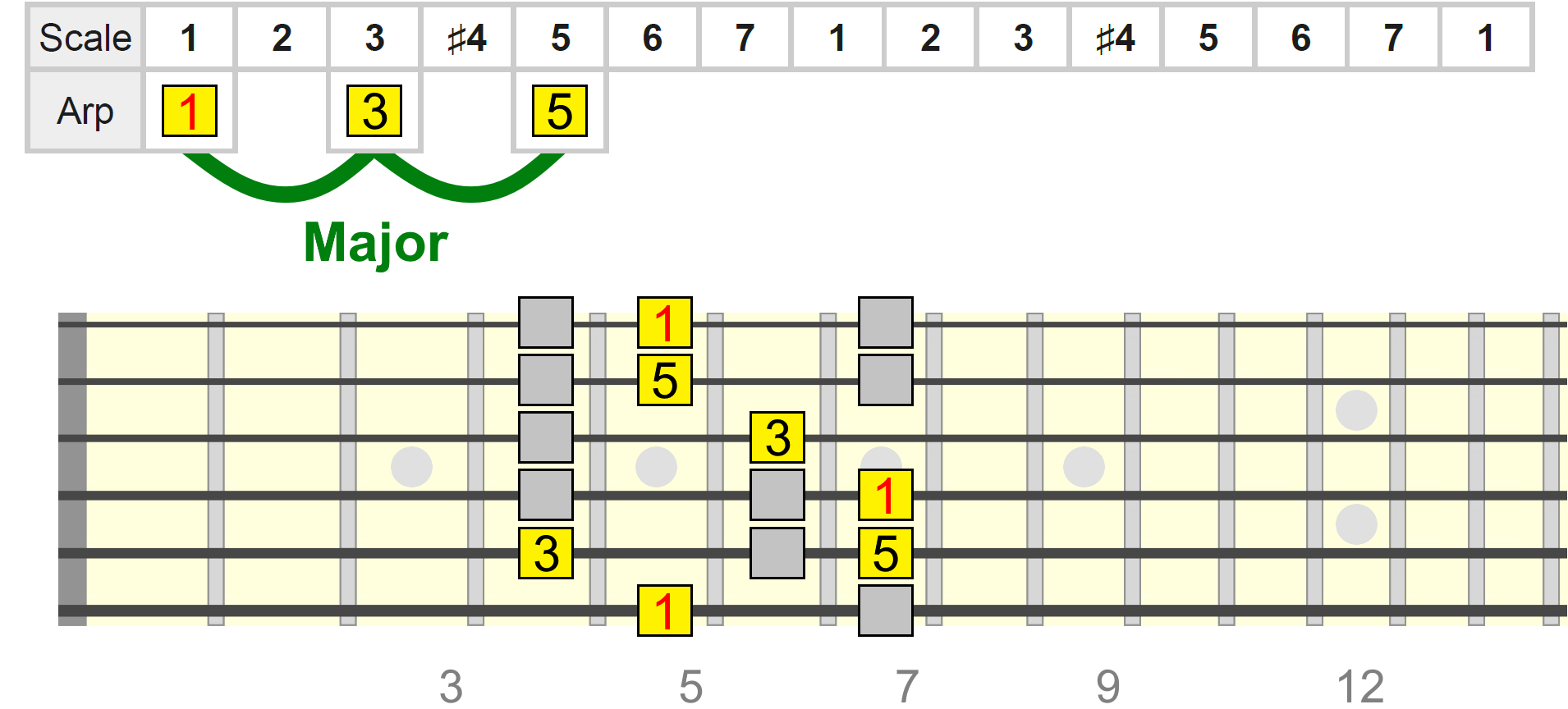

Arpeggio Fragments - Scale Triads

We're now going to compartmentalise the scale into simpler arpeggio fragments. This is so we can more concisely connect vertical and horizontal movements in our lead phrases (as we will later).

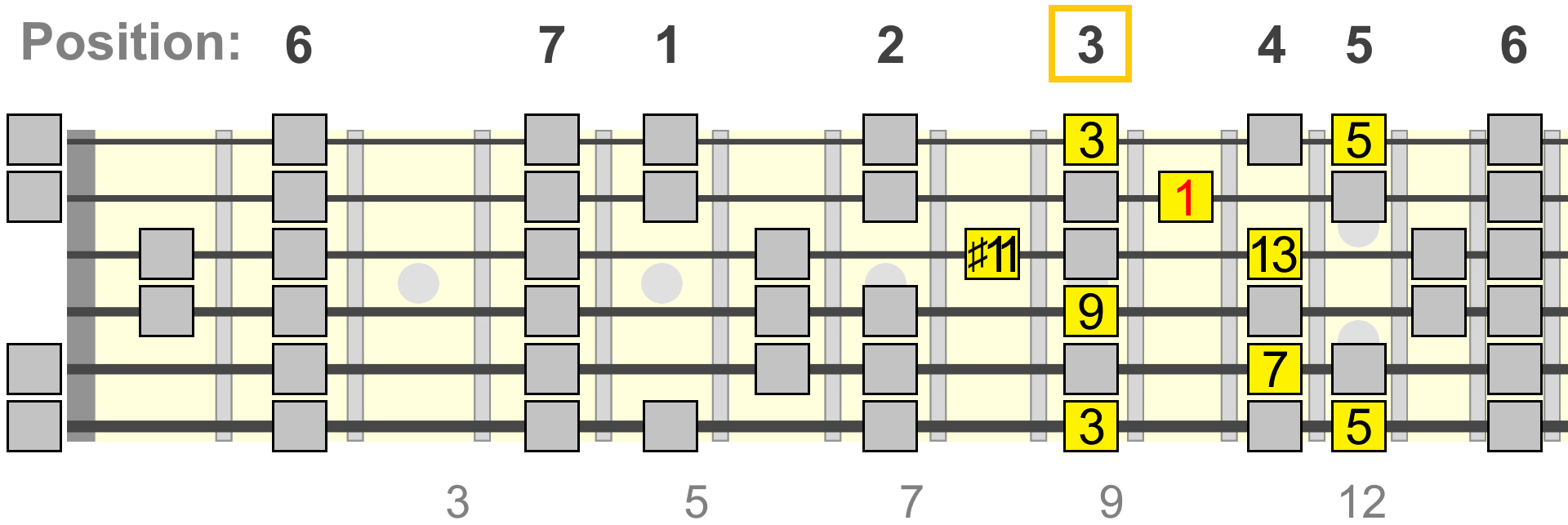

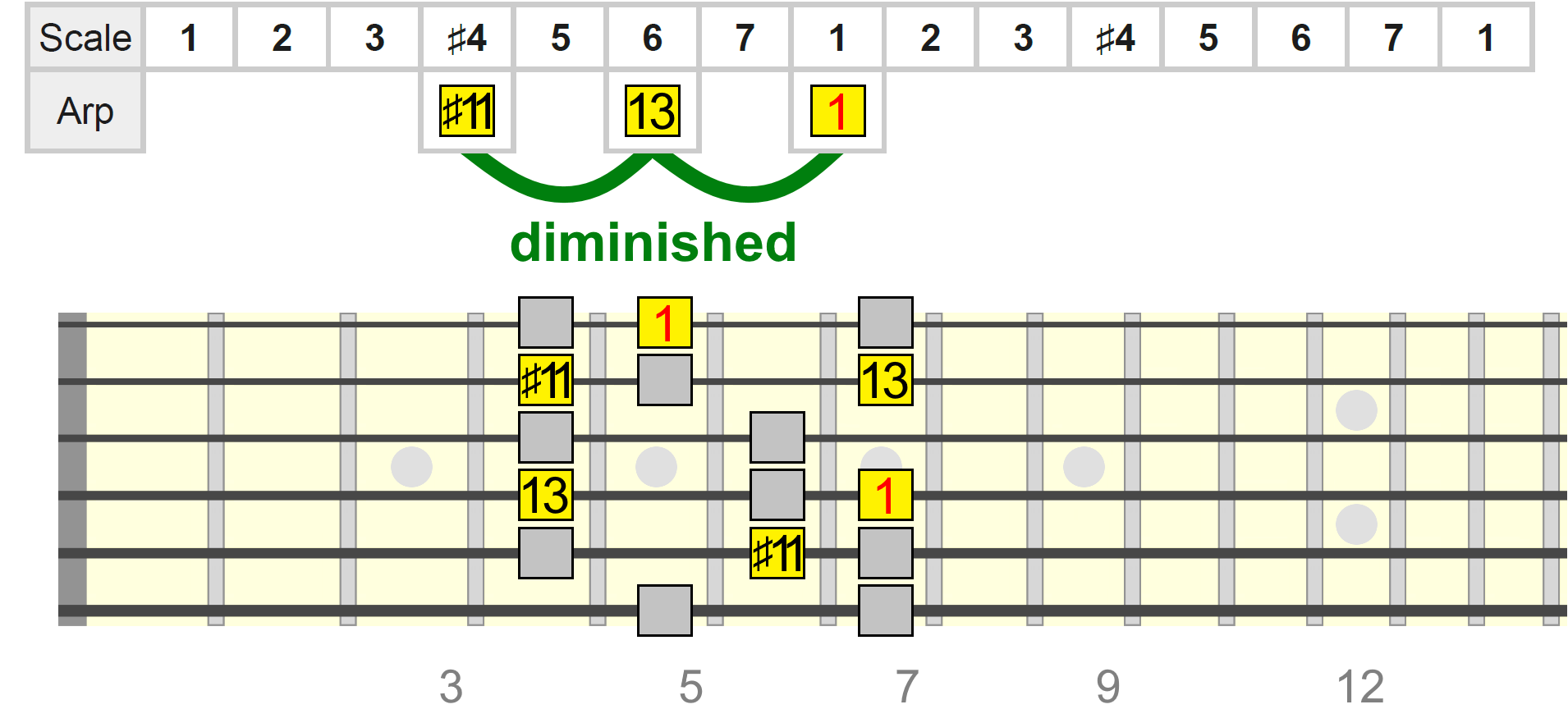

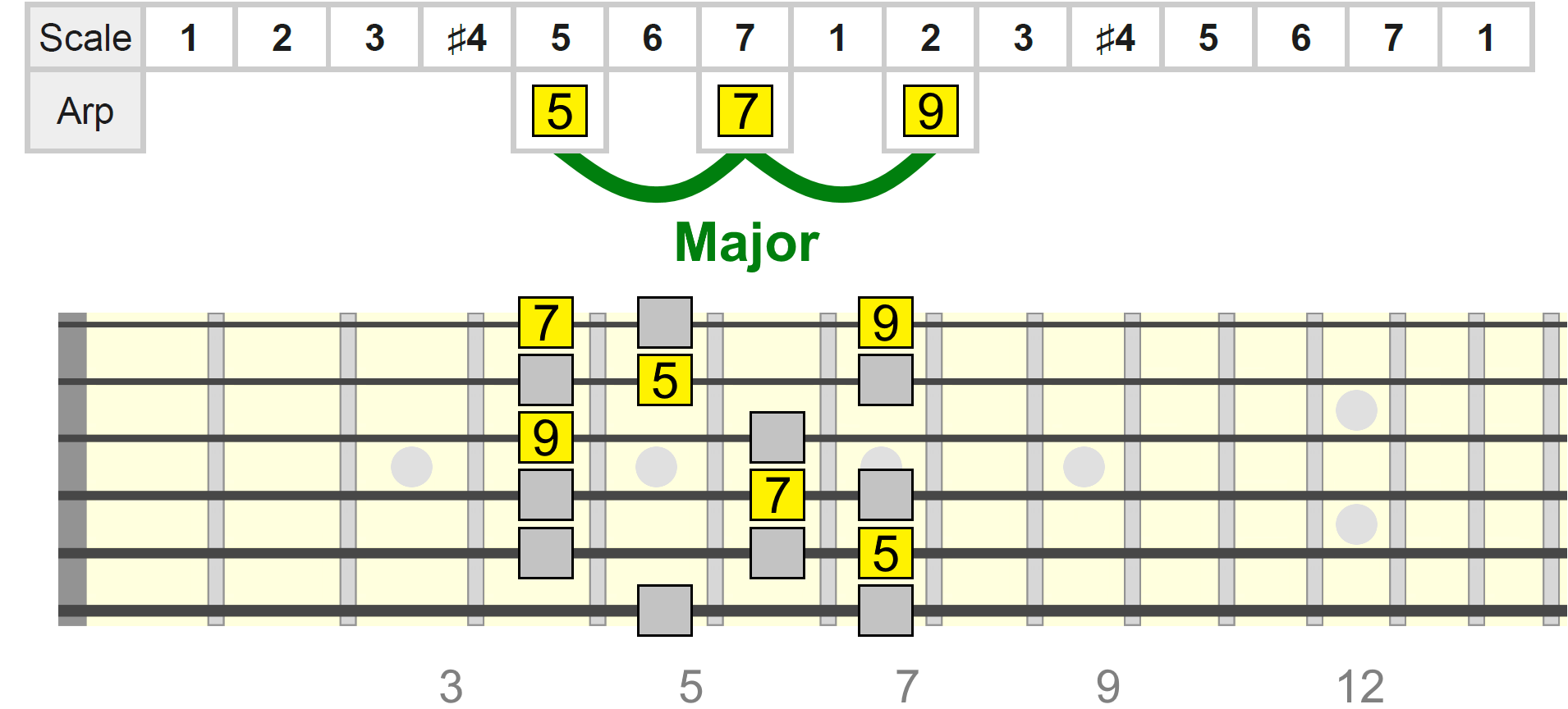

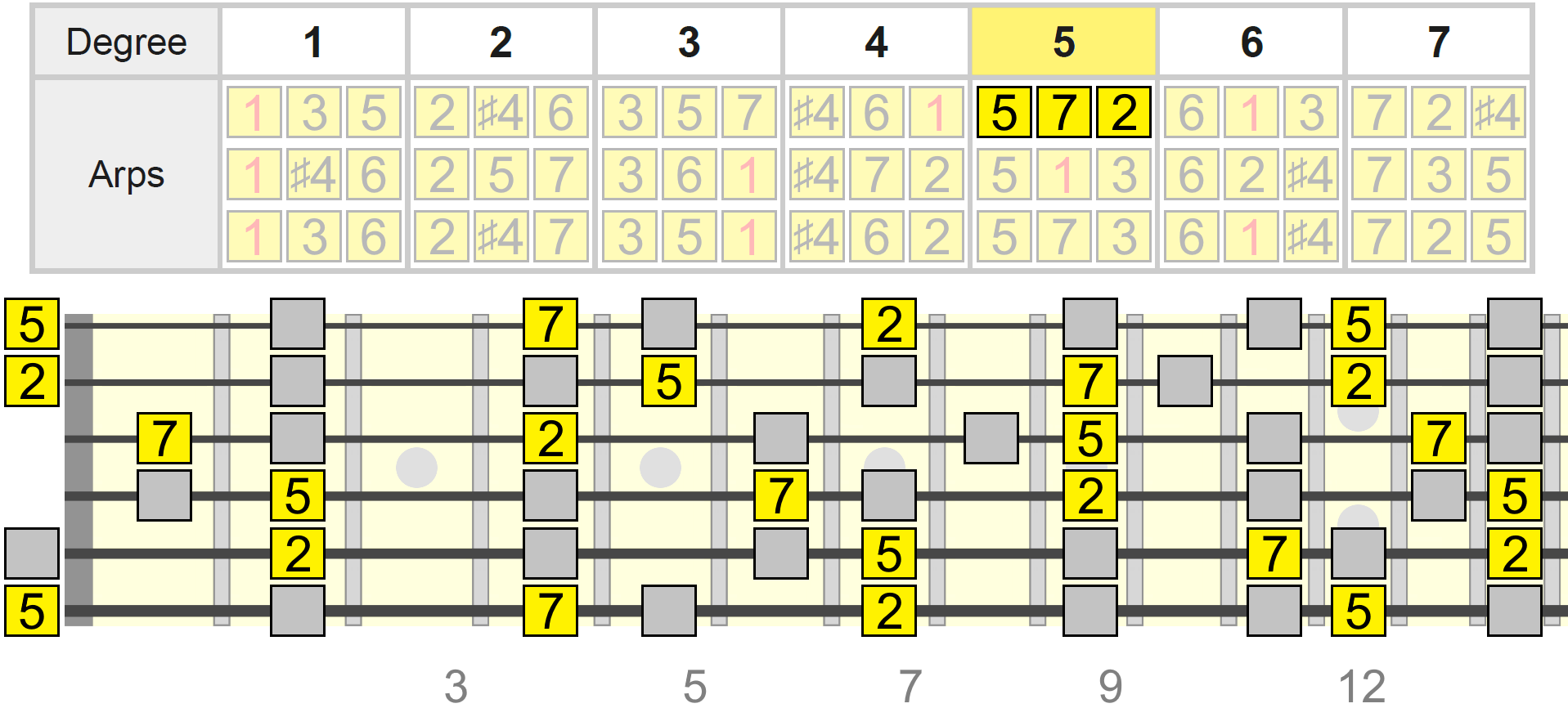

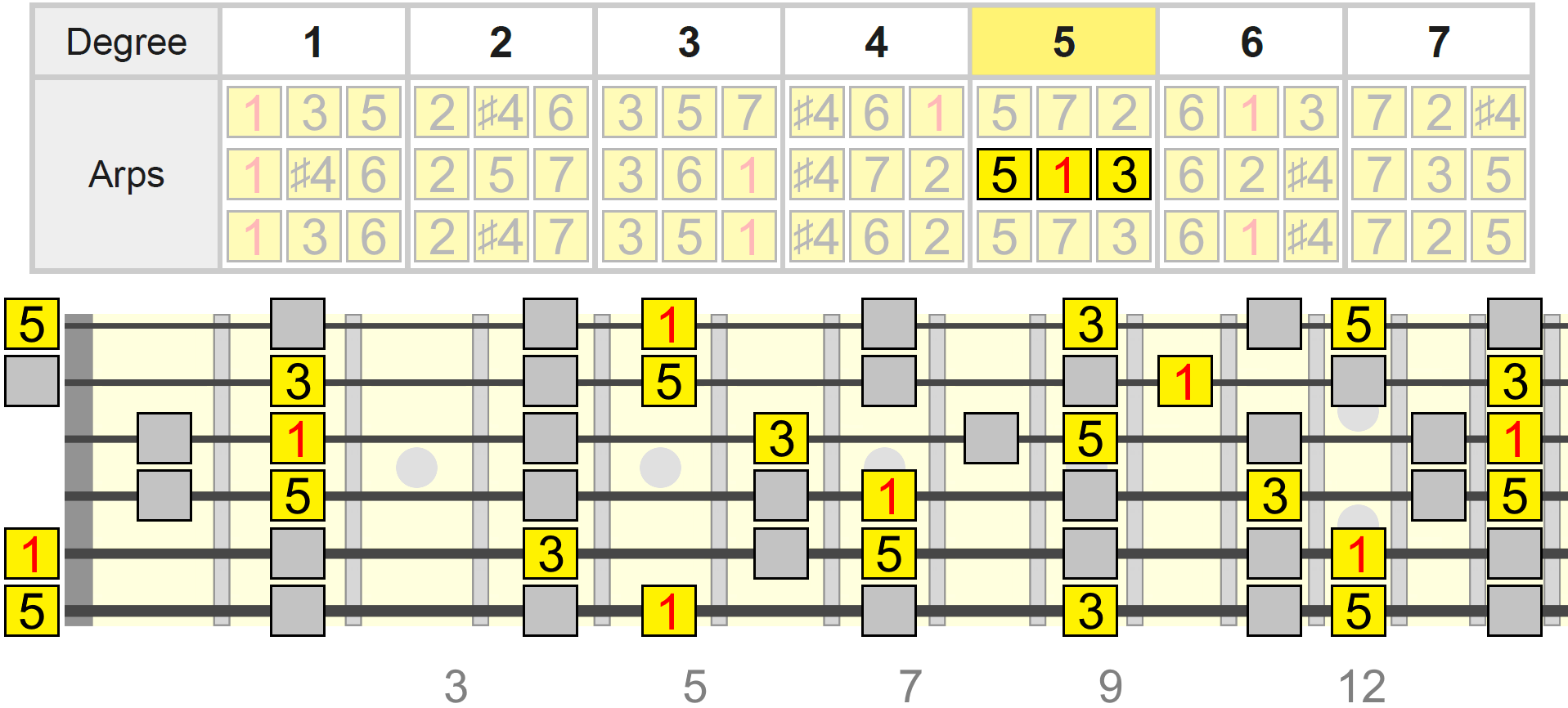

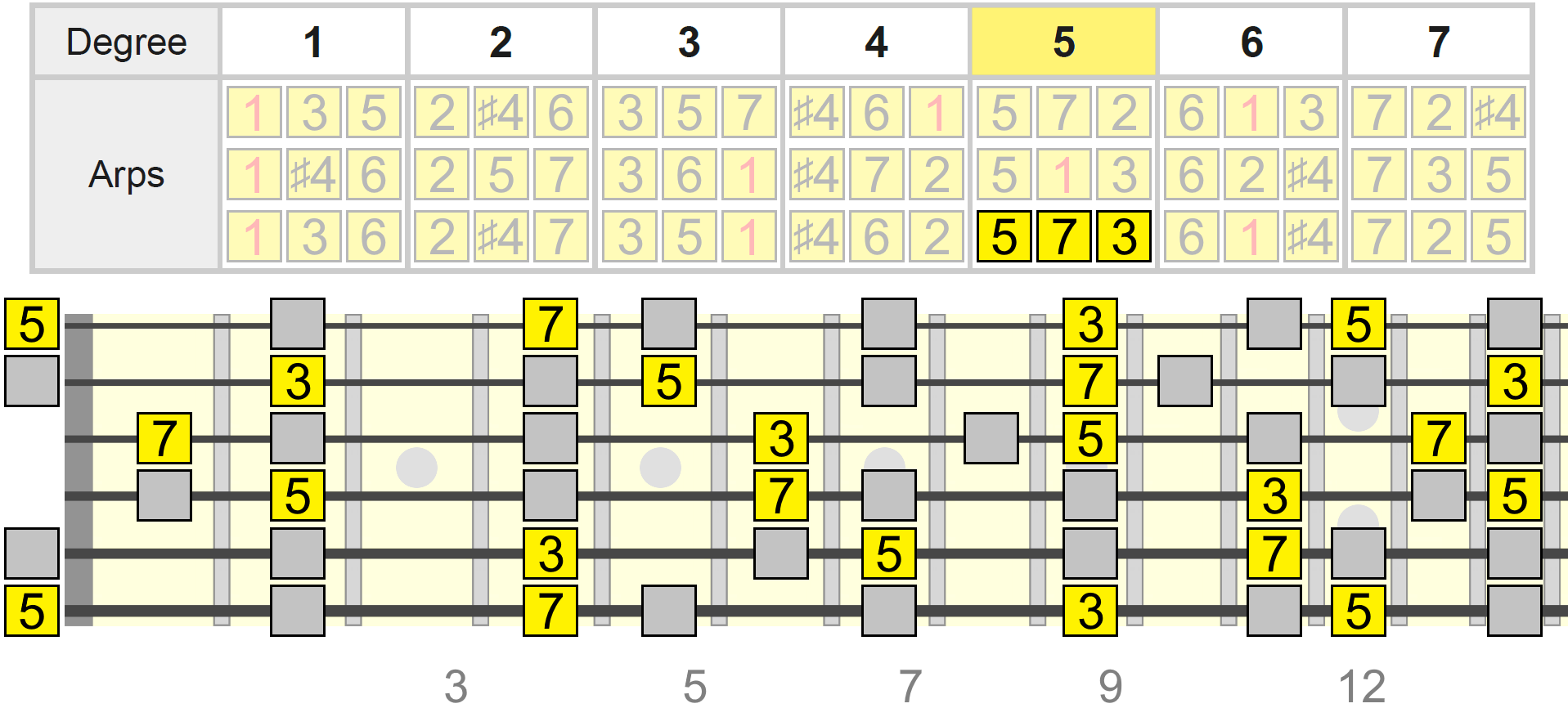

As you may already know, scales can be harmonised using triads. Each seven tone scale contains seven triads, again derived from stacking 3rds on each degree. And remember - where there's a chord, there's an arpeggio. This means we effectively have access to seven arpeggios within the scale for our phrasing, each of them representing a fragment of the complete arpeggio from earlier.

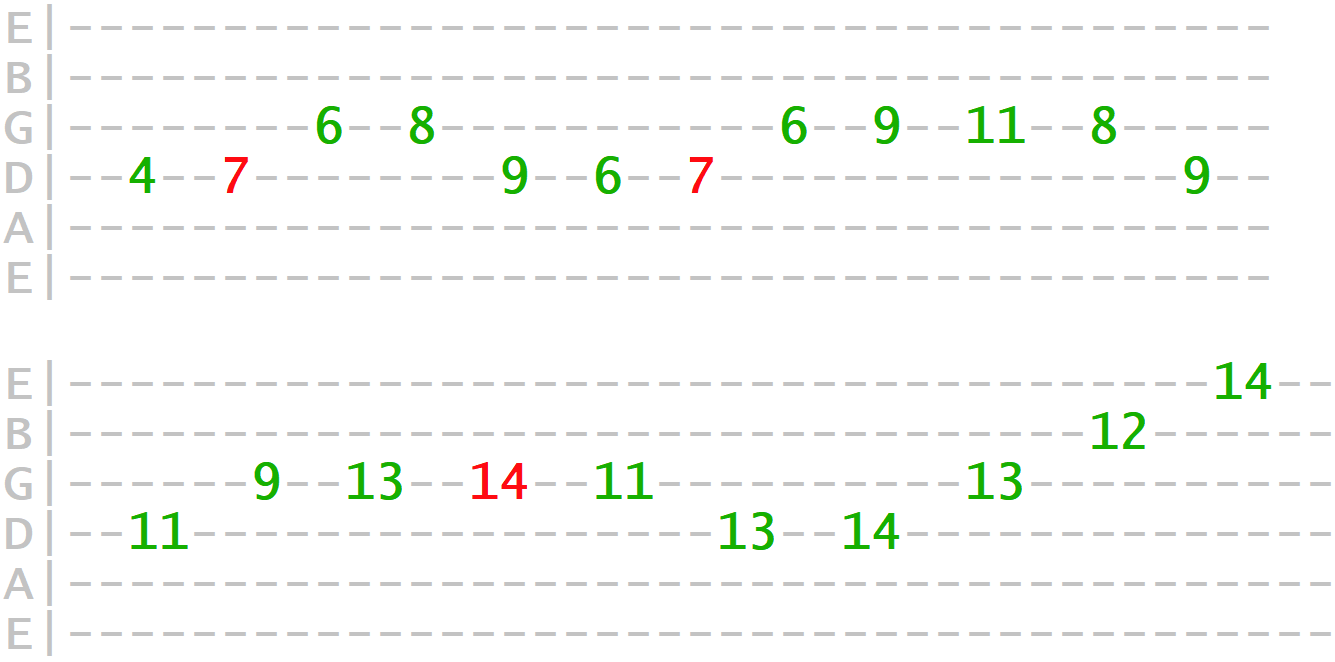

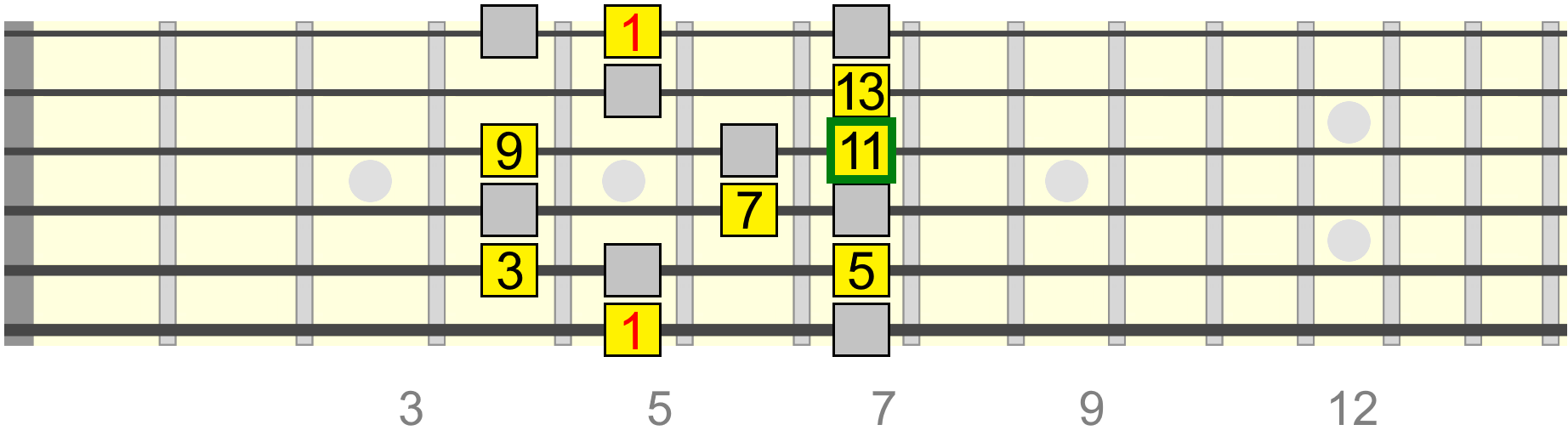

Back to Lydian's 1st degree pattern, we can build a triad arpeggio on each degree as follows...

So we're essentially moving through the scale using a sequence of integrated arpeggios, just as we might when harmonising it using chords. When learning scales, it's very useful to also learn the scale in triads. For example, Lydian's triad sequence is: M M m d M m m.

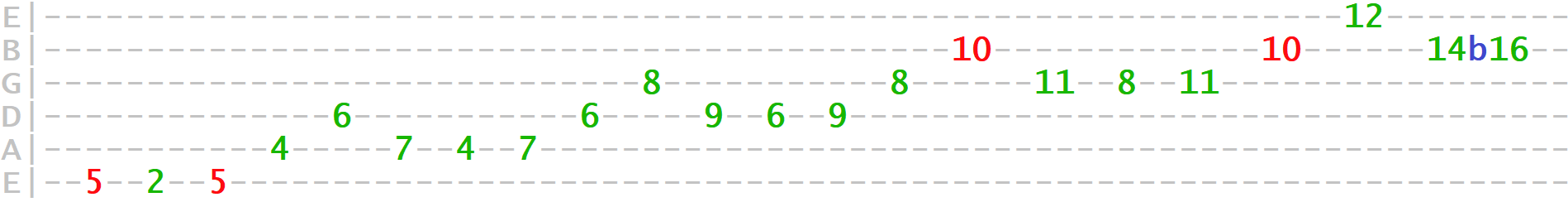

And just like before, we can play these triad arpeggios in different neck positions. Such as this example on the top two strings, where we descend through the sequence of scale triads...

Or this example on the 3rd and 4th strings (with the exception of the final part), this time climbing through the triad sequence of the scale. Every three tones represents a triad from the scale...

Experiment with connecting these arpeggios in different ways, using both ascending and descending sequences. For example, here we link the major arpeggio from the 1st degree, the major arpeggio from the 5th, the minor arpeggio from the 7th and the major arpeggio from the 2nd degree...

Here's the full sequence played out...

The more we learn to move around the scale pattern in this way, the more these arpeggio fragments will jump out.

Merging Vertical & Horizontal

We can now start to merge these arpeggios with more linear scale movements. For example, we could lead an arpeggio into or out of a linear sequence from the scale.

Let's start on the tonic major arpeggio and see where it takes us...

We're now close to another major arpeggio built on the 2nd degree (here again with a lead-out sequence)...

Here we lead into and out of the same 2nd degree arpeggio as above...

Now leading into and out of a descending arpeggio built on the 5th degree...

And finally leading out of a phrase with an arpeggio built on the 7th degree...

Let's now hear the connected sequence in full...

The more we practice integrating these arpeggios into our scale movements, the more intuitively we'll be able to setup and serve melodic phrases from the different places the arpeggios take us.

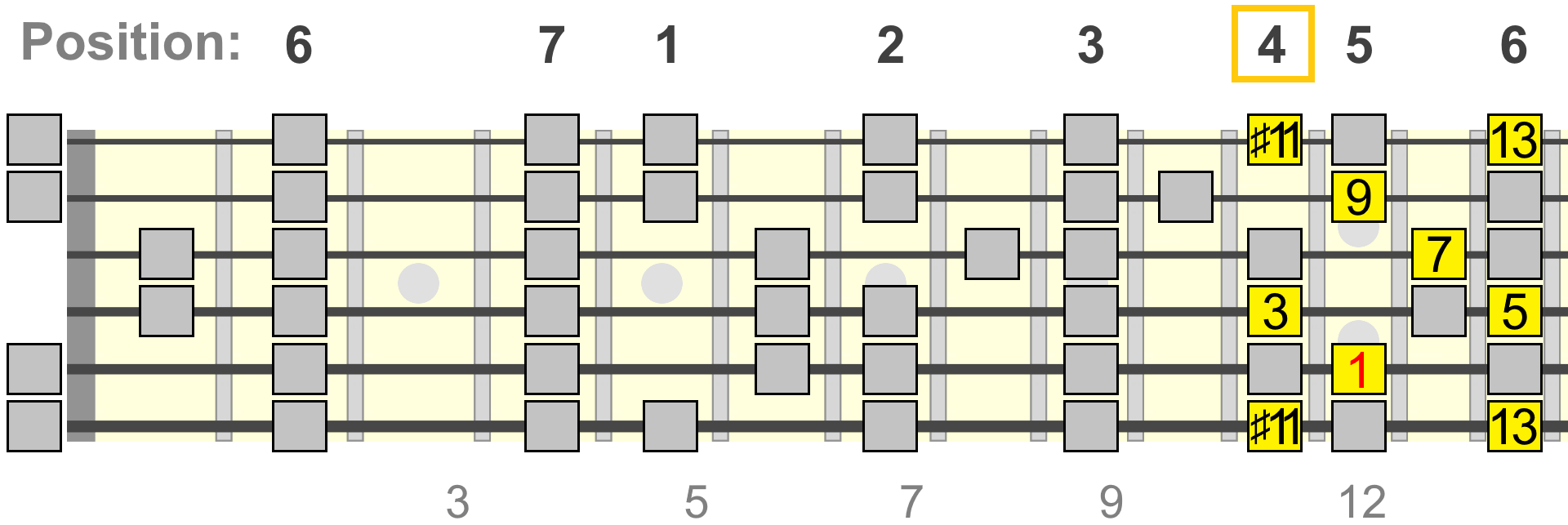

One tip here is to become aware of the tones we begin or land on in our phrases. Every tone we might begin or land on in a scale can potentially become the start of three related arpeggio sequences, whether ascending or descending from that tone. For example, from the 5th degree we have the following arpeggio options...

In the context of A Lydian, three of its integral triad arpeggios - E major, A major and C♯ minor - contain the 5th of the scale. So if we found ourselves on the 5th, we'd technically have three options for moving vertically from that tone.

For example, descending from the 5th through A major...

Another example, this time ascending from the 5th through E major...

So the challenge here is to be able to identify which arpeggio is available from each tone in the scale, as we did earlier. Start by building arpeggios on the chord tones of the tonic chord of the scale (A major in these examples) - root, 3rd, 5th and 7th (again, use a chord track to help).

Eventually you'll see numerous vertical patterns extending from any position you might find yourself in, just as we learn to associate a neck position with a scale pattern.

Shared Patterns (Modes)

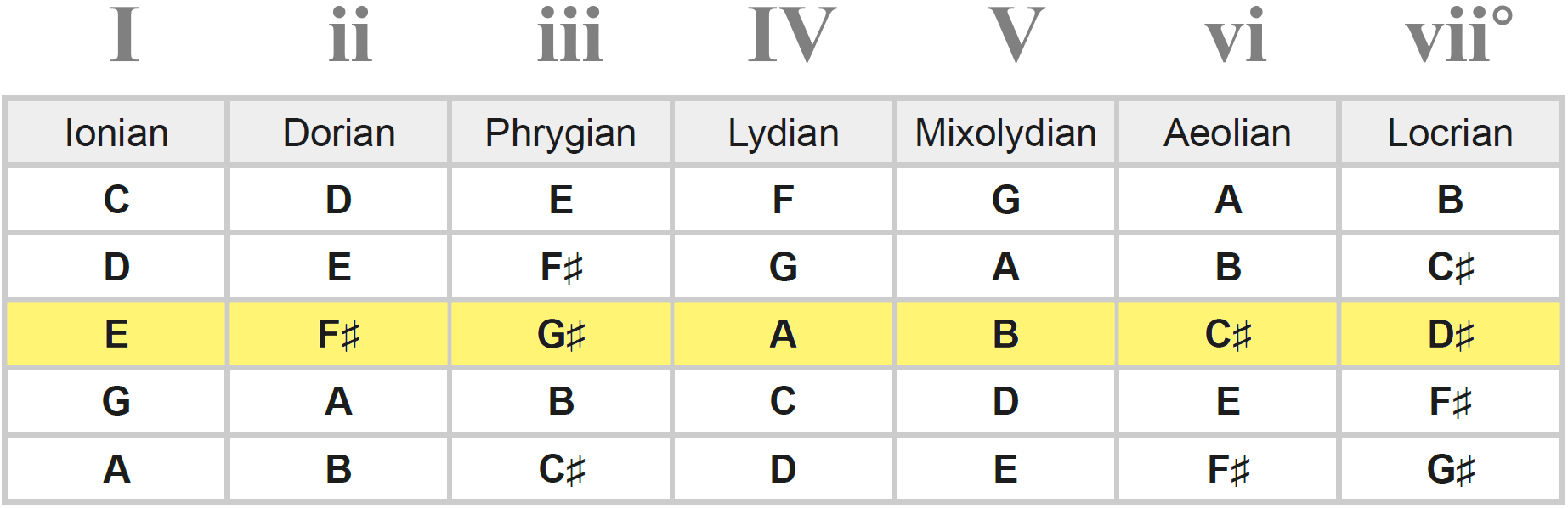

As Lydian is a mode of the major scale, its pattern, and therefore sequence of arpeggios is the same as six other scales. For example, A Lydian uses the same sequence and therefore pattern and positions as the E major scale or E Ionian, F# Dorian, G# Phrygian, B Mixolydian, C# Aeolian and D# Locrian...

This is good news, since it means one rolling sequence and therefore pattern of stacked 3rd arpeggios (i.e. the ones we learned in this lesson) can cover an entire diatonic major or minor key or mode.

So we can use the same concept we learn about how modes relate to one another to avoid having to learn a completely new pattern for each one.

For example, referencing an A Lydian sequence from earlier, listen to how that exact same sequence, with the same integrated arpeggios, sounds over F♯ minor, in the context of its related Dorian mode...

Over Amaj (A Lydian)

Over F♯m (F Dorian)

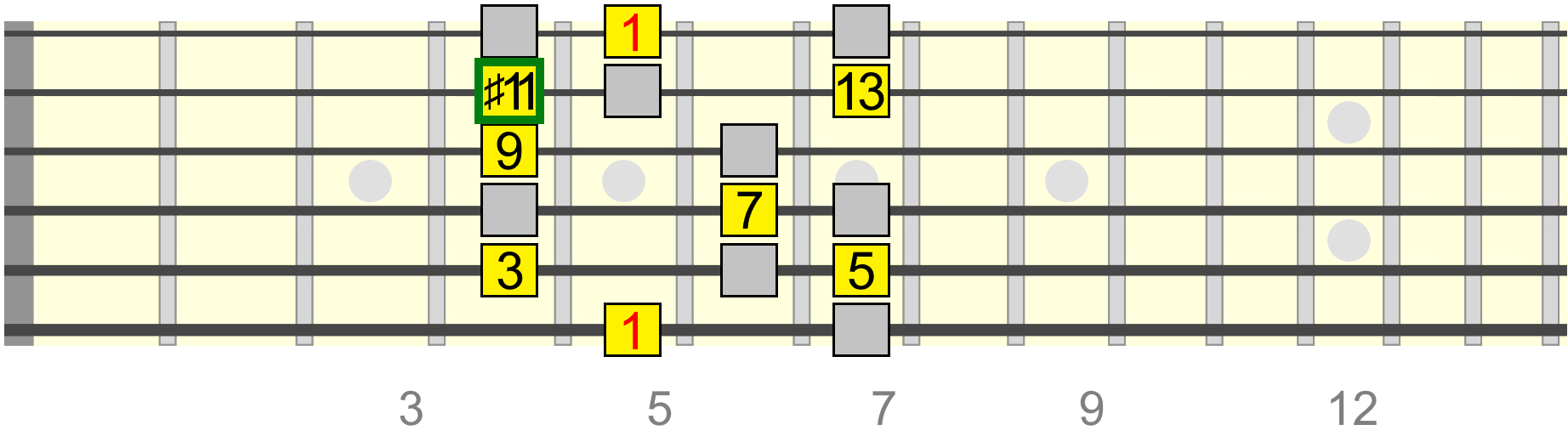

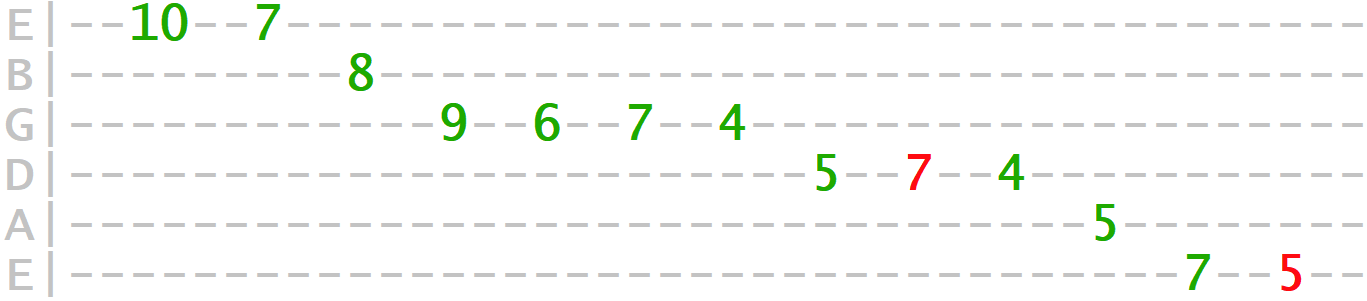

And what was the complete A Lydian arpeggio becomes F♯ Dorian's own native arpeggio, since we're stacking thirds in exactly the same sequence and therefore pattern. Dorian's own native chord and therefore arpeggio is a minor 13th (e.g. F♯m13) - a minor triad, with a minor 7th and a 9th, 11th and 13th as extensions...

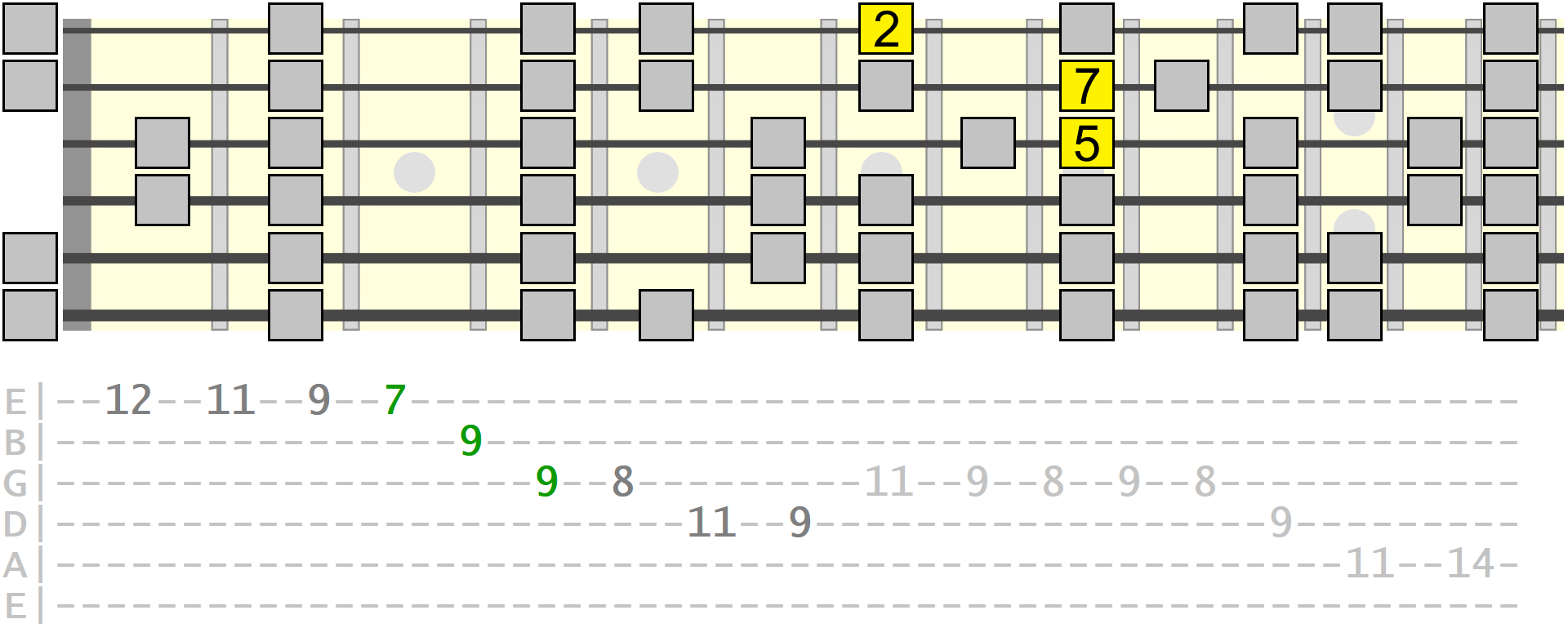

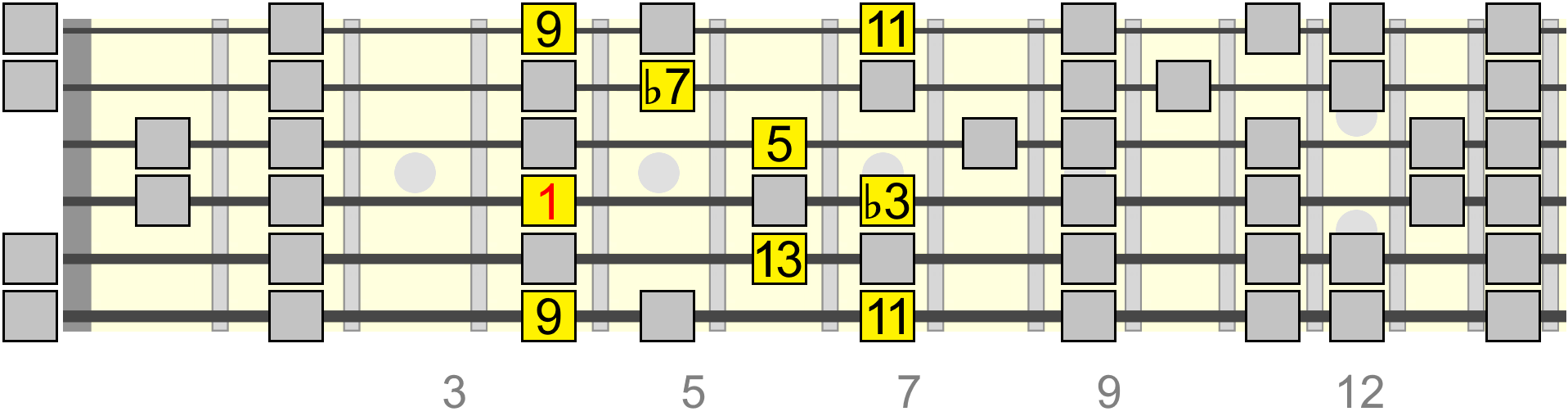

Of course, we can use exactly the same rolling sequence of box positions to connect up Dorian's arpeggios, just as we did with Lydian and would with any other mode of the major scale...

Try playing through these patterns using an F♯m chord track.

Here we connect up two of the box patterns (note this would also work over A major for Lydian)...

Remember that we don't always have to play through the full six string pattern. We can break it up into two, three and four string fragments, whether using the triad technique or just fragments of the full arpeggio sequence.

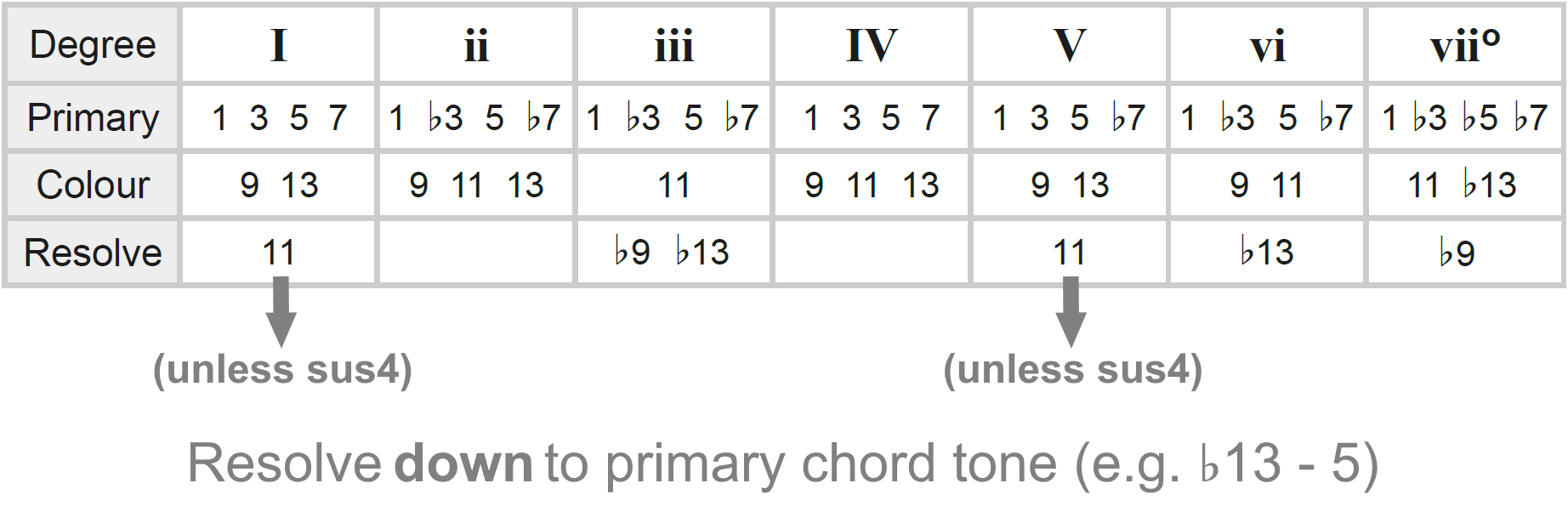

Resolving Passing Tones

There's one thing to be a little cautious of when applying this stacked 3rds concept to Ionian - the natural scale of the tonic chord in a major key progression.

Let's say we were playing A Ionian over the tonic A major. We can stack 3rds just as we did with Lydian. But you'll notice that Ionian has a perfect 4th instead of augmented 4th degree...

This would effectively make Ionian's native chord and arpeggio a major 13, but with the natural 4th or 11th in the stack.

In a melodic context, this tone is considered rather dissonant over major chords with the same root, because of how it clashes with the major 3rd, one semitone below. So if we play the 11th as part of an arpeggio sequence, we might hear something is a little off...

One way to avoid this dissonance is to resolve it down to the major 3rd, so it becomes a passing tone (the arrow indicates the 4th/11th of the arpeggio resolving to the 3rd)...

The same could be applied to Mixolydian as that too has a perfect 4th/11th interval which clashes with the major 3rd of its tonic chord...

However, if the chord we're playing over has a suspended 4th quality, then the 4th or 11th becomes more naturally harmonious.

Here I'm playing over an A suspended 9th chord with various arpeggio fragments from Mixolydian...

So just be aware that we still have to use our ears to determine if a tone within the arpeggio we use needs to resolve somewhere more stable, i.e. a primary chord tone...

Final Notes...

While the aim here is not to crowd out our solos with arpeggios, by injecting them into our more linear movements, we can give the journey of our lead an additional vertical expression, using wider interval jumps to help shape our phrases, and discover the new places that takes us. Start with individual chords and scales to get a feel for this and then gradually introduce chord changes. Use a chord track creator to give you that backing.

In future lessons I plan to explore individual scales in a vertical manner, including scales like Phrygian dominant and melodic minor. In the meantime, I hope this lesson has at least given you a new concept to explore, beyond regular scale navigation. There is genuinely a lifetime's worth of skill in this lesson, which you can apply to any scale and in any playing situation.

Take your time with it as always, and be reassured that the fruits of all this will soon be realised.