Home › Progressions › Dominant Substitution

Dominant Substitution - Approaching the Tonic

The dominant (or V - 5th degree chord) is a common chord for approaching the tonic (or "home") of a key. But we can create variation by involving chord substitution - literally replacing the dominant with another chord, but maintaining a similar function and direction - a gateway to resolution.

So we're still going for that satisfying "homecoming" sound that the dominant would naturally facilitate. But we're going to use chord degrees and qualities that have more of an "outside" feel. Because of the notes shared between these substitutions, the dominant and tonic, there's enough of an interconnected flow of harmony for them to work well.

As with many of my lessons, there'll be an ear training element and a spatial awareness of how these substitute degrees, and their various chord qualities, form on the guitar neck in relation to the tonic.

The Minor iv

Often called a "minor plagal cadence", here we take the otherwise very restful movement from IV to I (e.g. F to C in the key of C major) and give it a sense of tragedy or longing (Fm to C).

You'll have heard it in countless compositions and composers have always been drawn to its seductively sombre quality. As well as being a IV substitute, it can also be seen as a dominant (V) substitute.

First, take a listen to a standard dominant approach to the tonic (V - I) vs the minor plagal approach (iv - I)...

C / Em / Am / G (I / iii / vi / V)

C / Em / Am / Fm (I / iii / vi / iv)

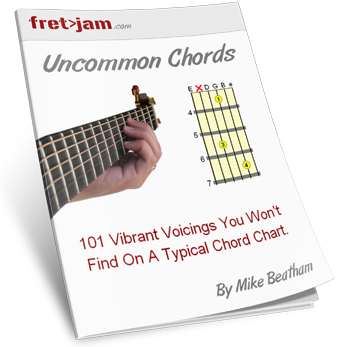

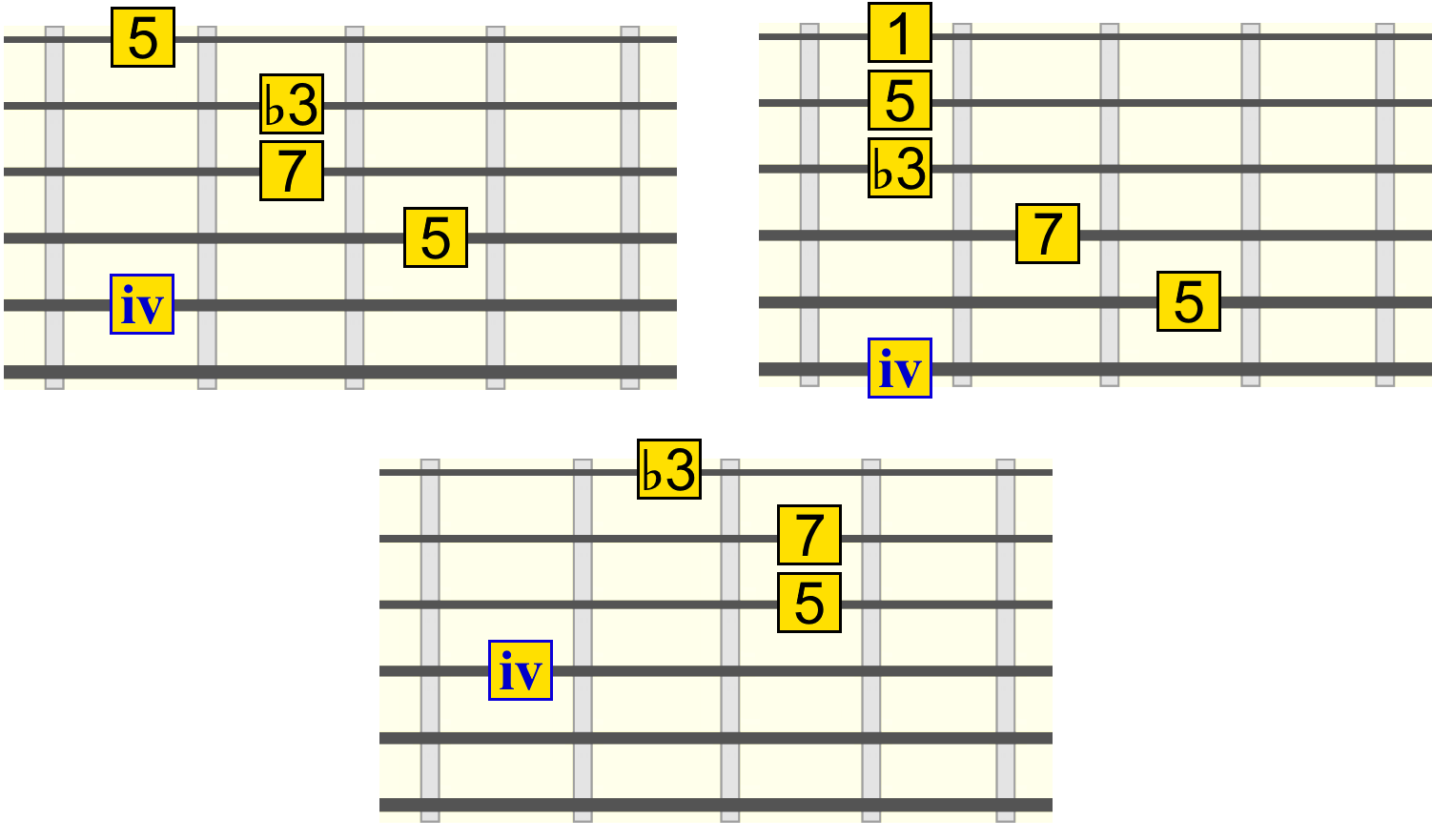

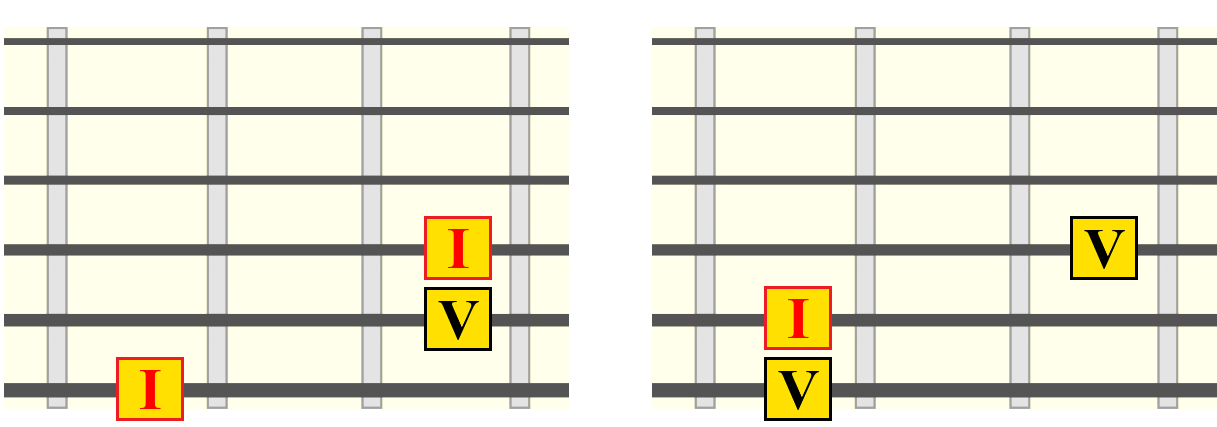

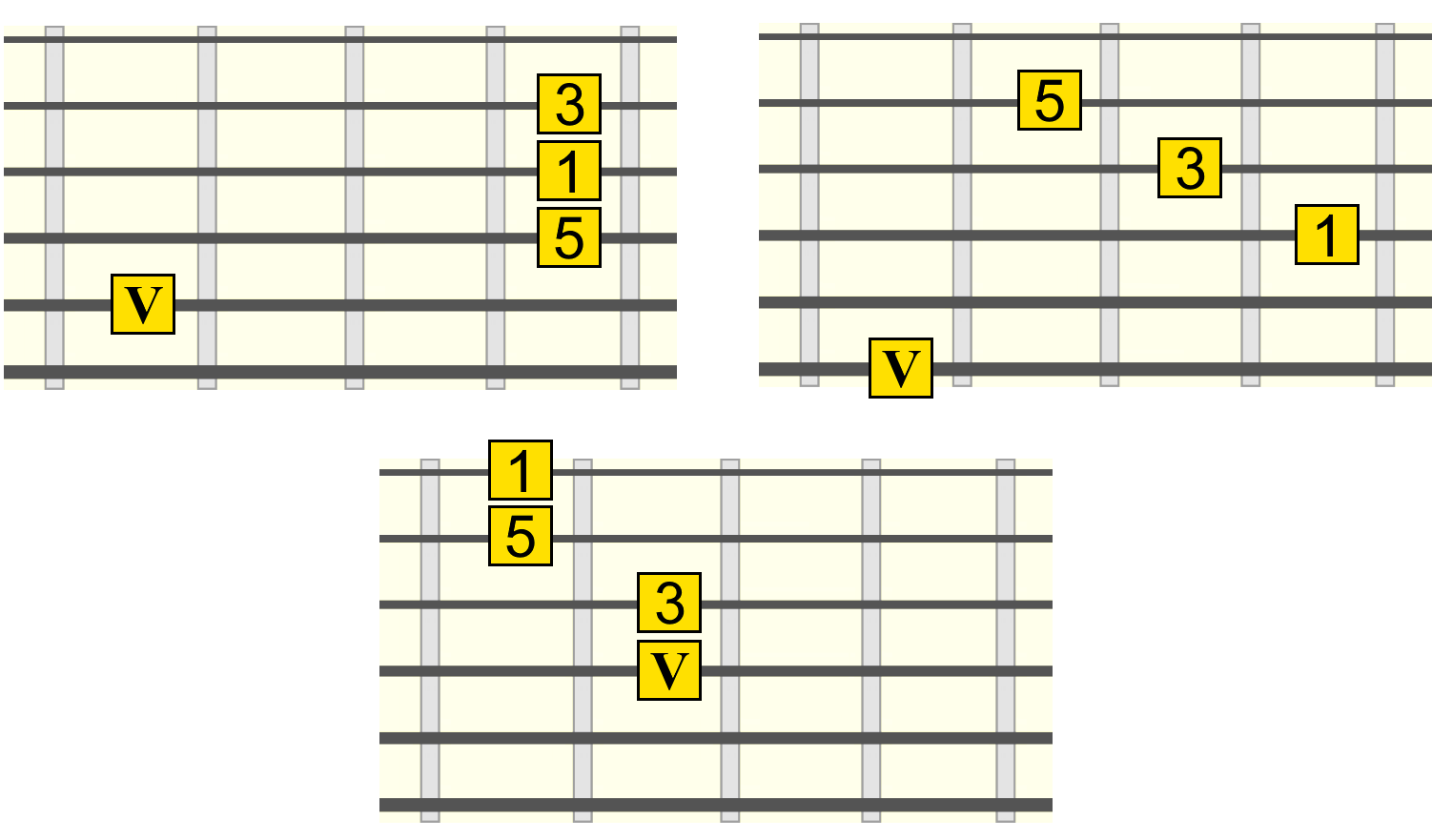

Since the minor iv shares the same root position as its more popular major IV (both 4th degree or "subdominant" chords), you'll likely already be familiar with the iv-tonic root relationship (e.g. F - C, G - D, A - E etc.). I've put them below for reference...

So in the above diagrams we have the tonic (I) or "home" root of the key on the lowest three strings, with its related root positioning for the iv (subdominant) and V (dominant). Throughout this lesson, these root string relationships will be useful to memorise (hint!), because we want to know where the non-tonic degrees are in relation to the tonic on any root string.

Let's look at some chord qualities that support and enhance this substitution on different root strings.

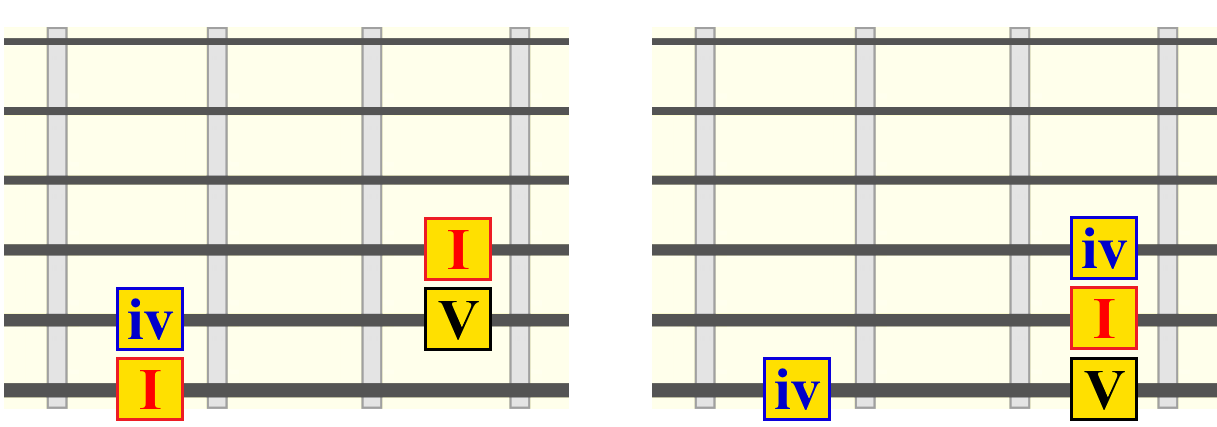

Minor 6th Shapes

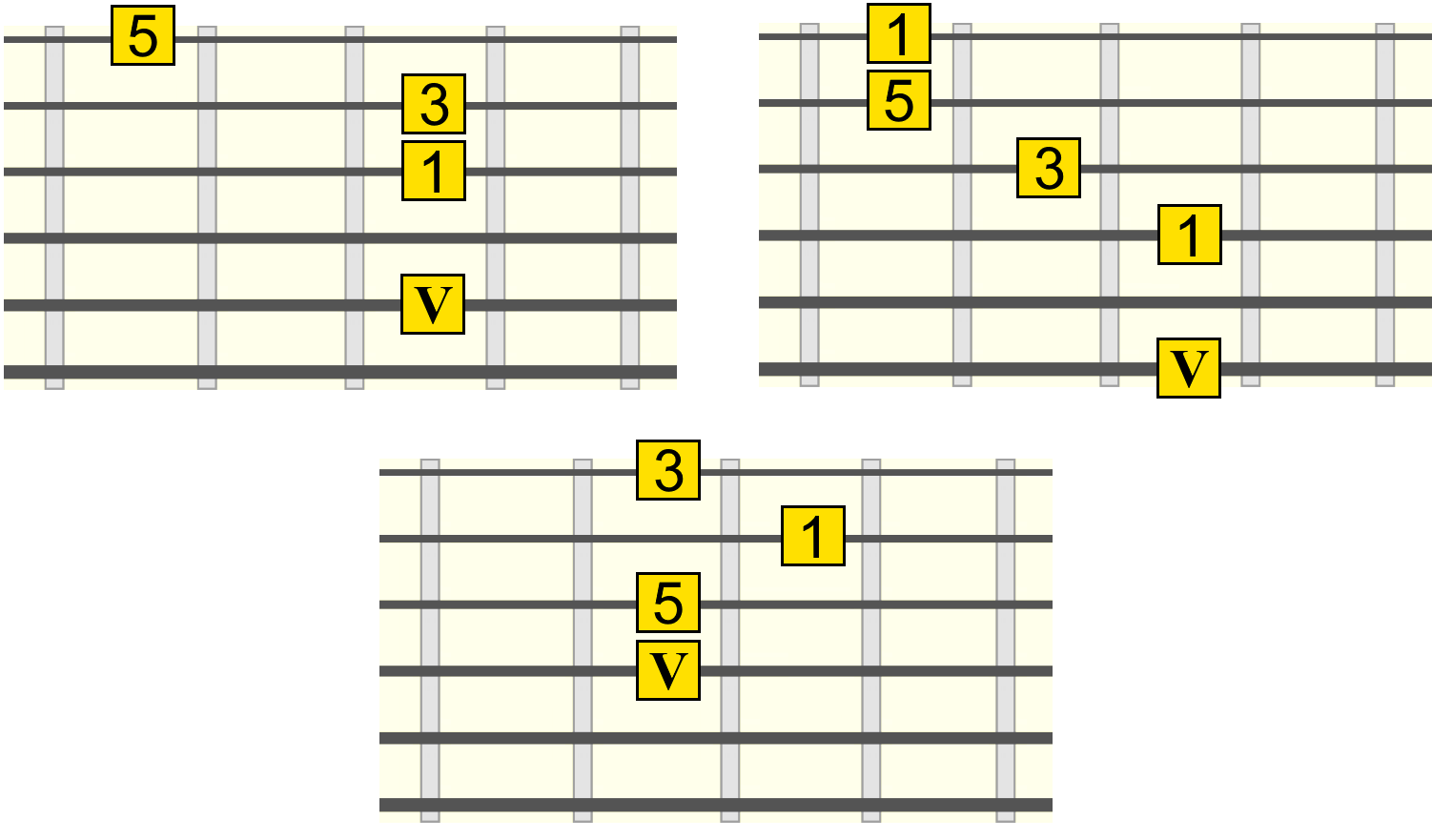

Adding the 6th to a minor triad colours it especially beautifully in this iv position. In the below diagrams, we're playing on the iv root as the bass of the chord on three root strings...

Tip: The tonic exists on the 5th of the iv. Just another visual reference we can use to find our way home.

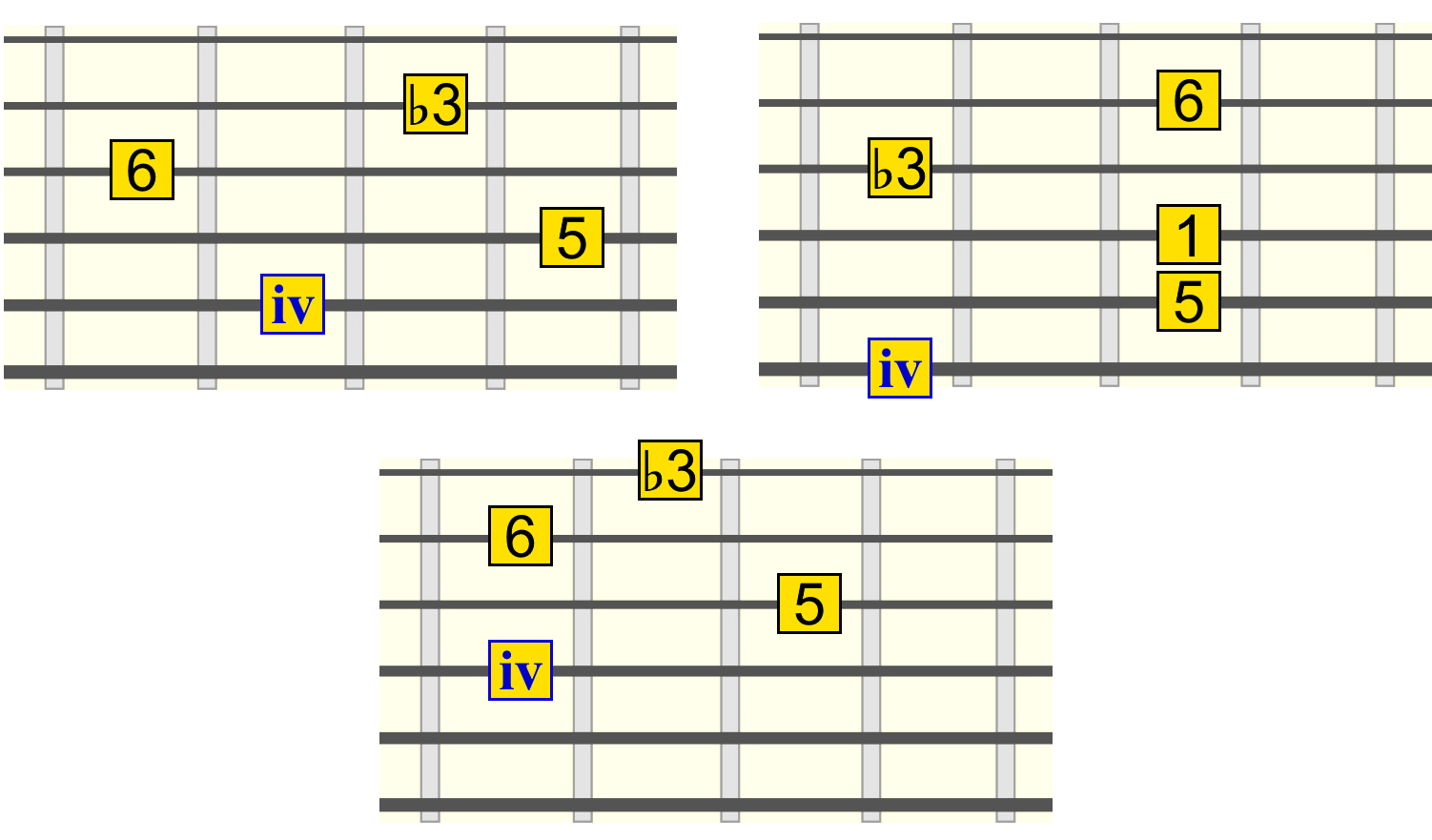

Minor 9th Shapes

To my ears a "softer" interpretation of the iv. But the 9th gives it a certain sweetness...

Minor/Major 7th Shapes

Arguably the most tense out of the three. The major 7th has a rather dissonant interplay with the minor 3rd, but the chord has a natural place on this degree...

Side note: With all these examples, the substitute chord can always lead to or from the regular dominant. For example, with the above in the key of C major, we might end a progression with:

Fm / G / C or G / Fm / C

In more general terms, we're thinking more creatively about how we can approach the tonic, when it's time to return home.

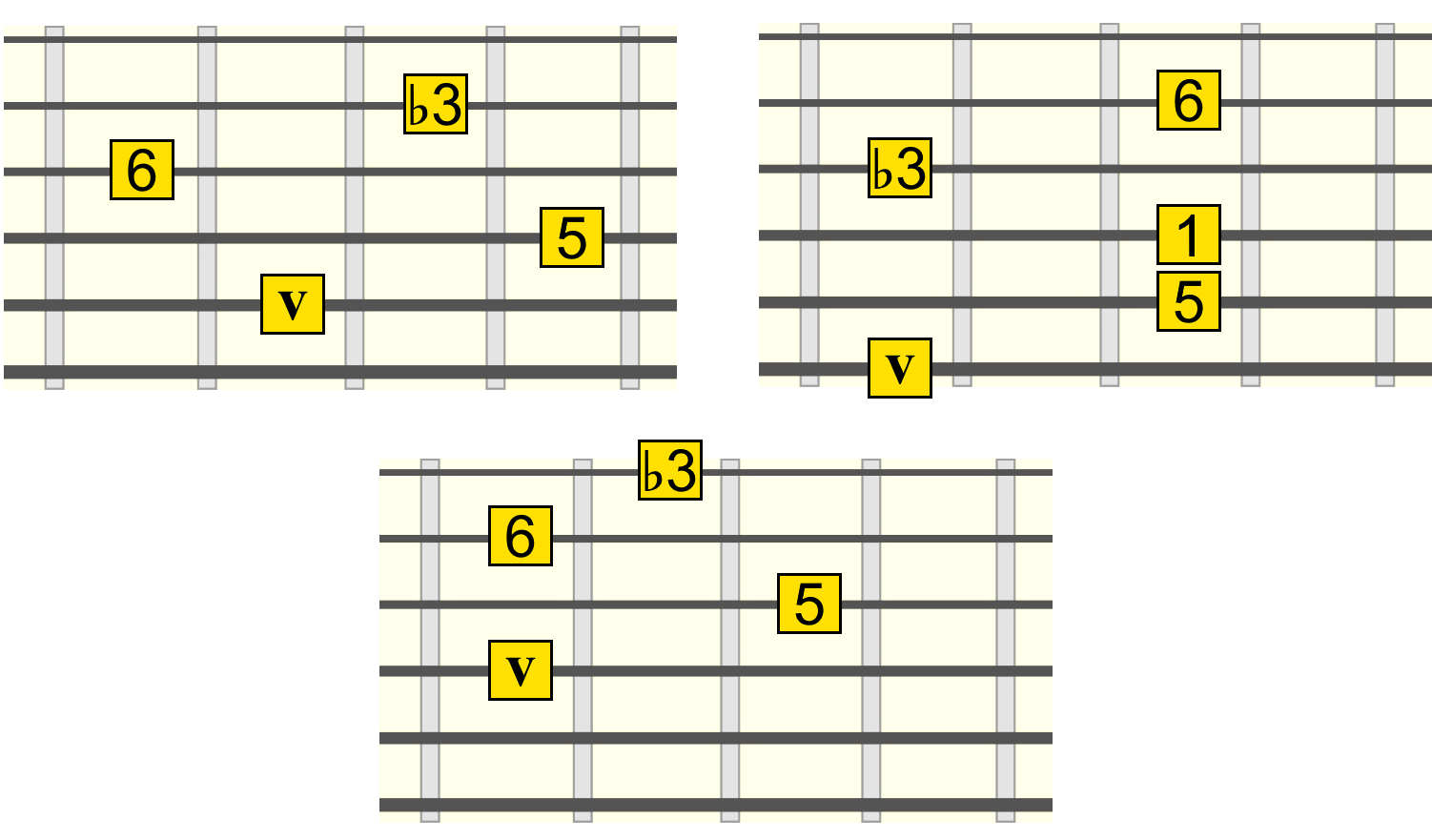

The Minor v

Our dominant can also be played as minor on its natural degree (e.g. Gm - C). While it doesn't have that strong dominant seventh function, it does kind of "open things out" in a less predictable way. Take a listen in the key of D major, first with a standard V - I ending, then with a minor v - I...

D / Bm / Em / A (I / vi / ii / V)

D / Bm / Em / Am (I / vi / ii / v)

The minor v also sounds really good falling to the IV, acting as the ii of the subdominant.

D / Bm / Am / G (I / vi / v / IV)

This substitution can be seen as borrowed from the Mixolydian mode, since Mixolydian's 5th degree chord is minor. Therefore, in the key of C (G dominant), we'd be looking to switch to C Mixolydian when that minor v is voiced. We'll look more at scale accompaniment with these substitutions another time.

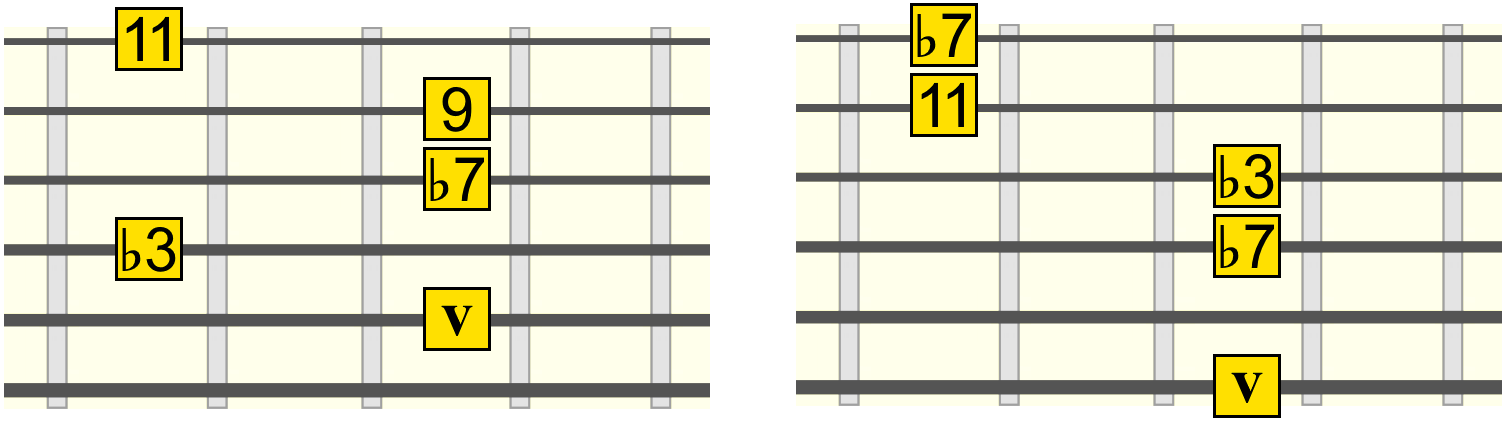

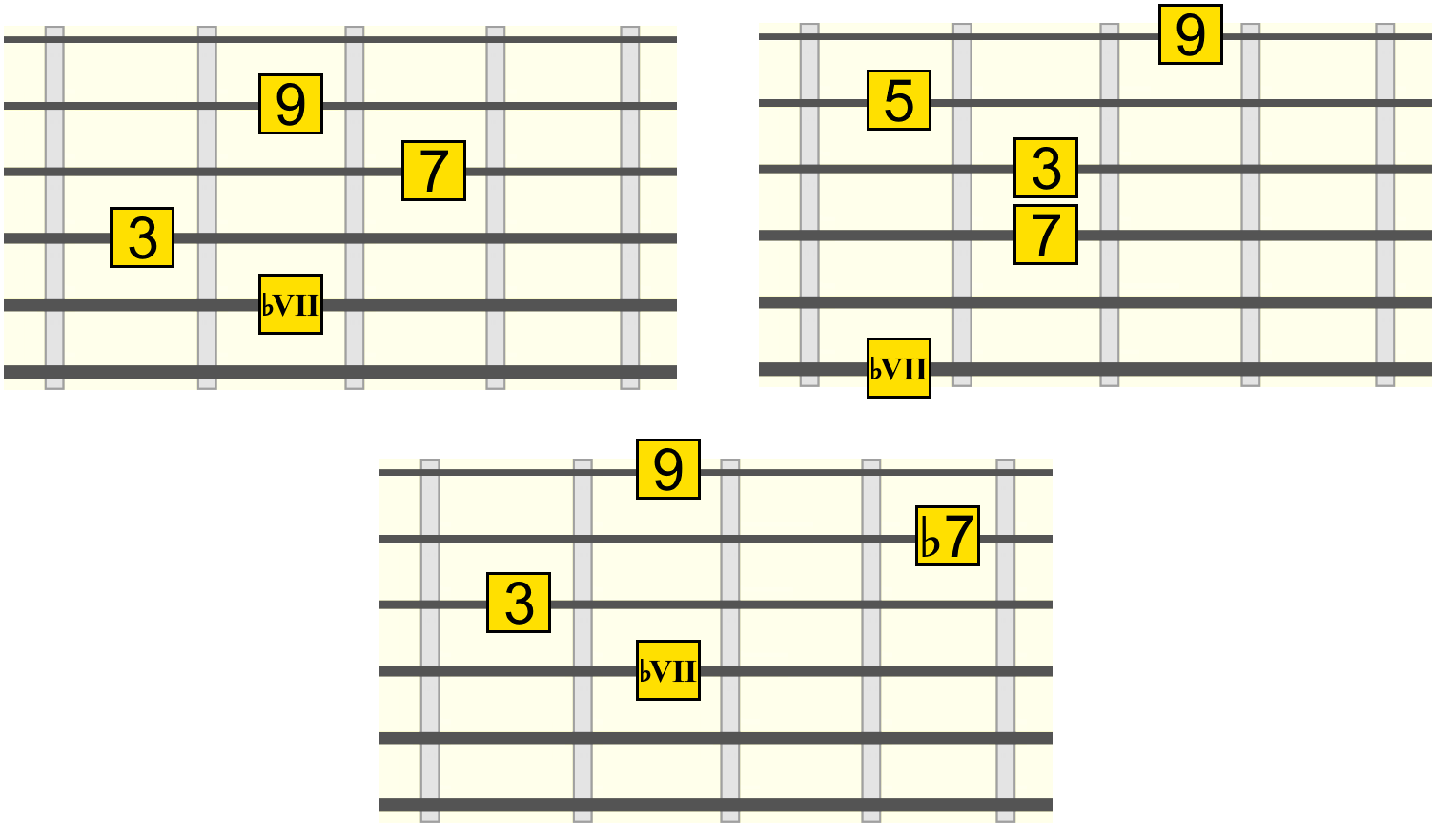

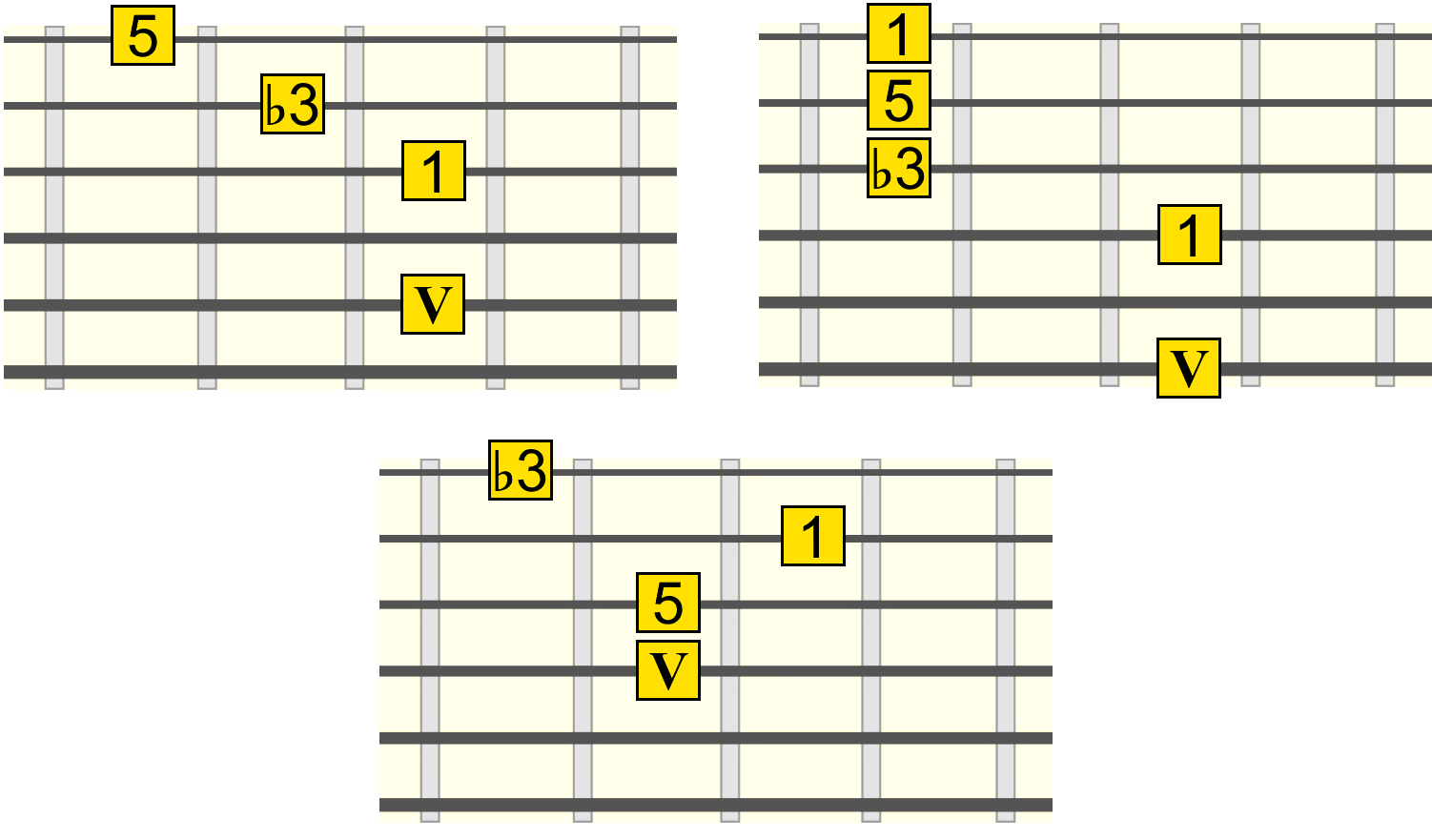

Some nice colour options...

Minor 6th Shapes

Minor 9th Shapes

Minor 11th Shapes

Side note: Feel free to use triads or seventh chords. The "colour" options I show are just to demonstrate the extended voicing potential of chords in these positions.

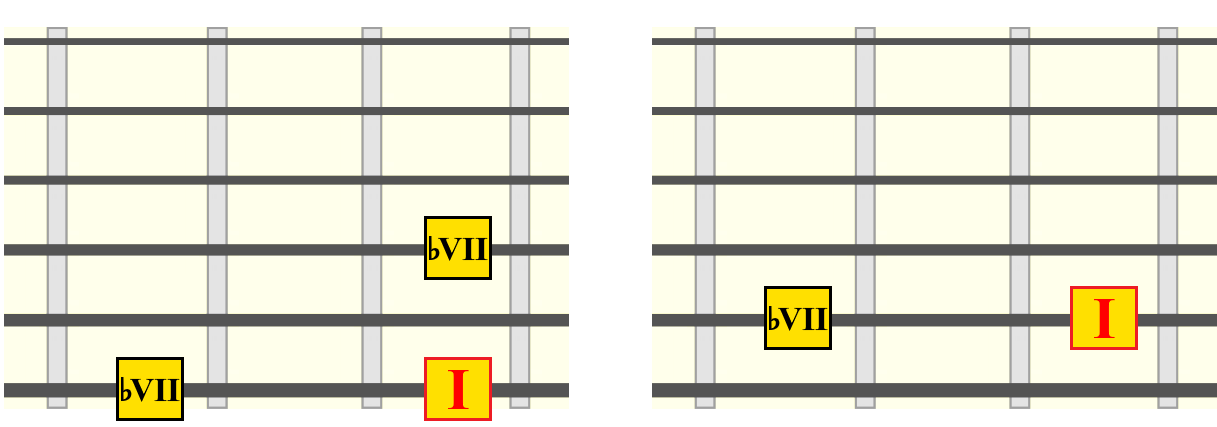

The ♭VII

Often referred to as the "backdoor" cadence because of the direction we approach the tonic. The degree can be visualised as a whole step (two frets) down from our major key tonic root, falling as the ♭VII (flat seventh or subtonic) degree.

Here's an example in the key of E, where D (both Dmaj7 or D7) is our backdoor approach in the second clip...

E / F♯m / A / B (I / ii / IV / V)

E / F♯m / A / D (I / ii / IV / ♭VII)

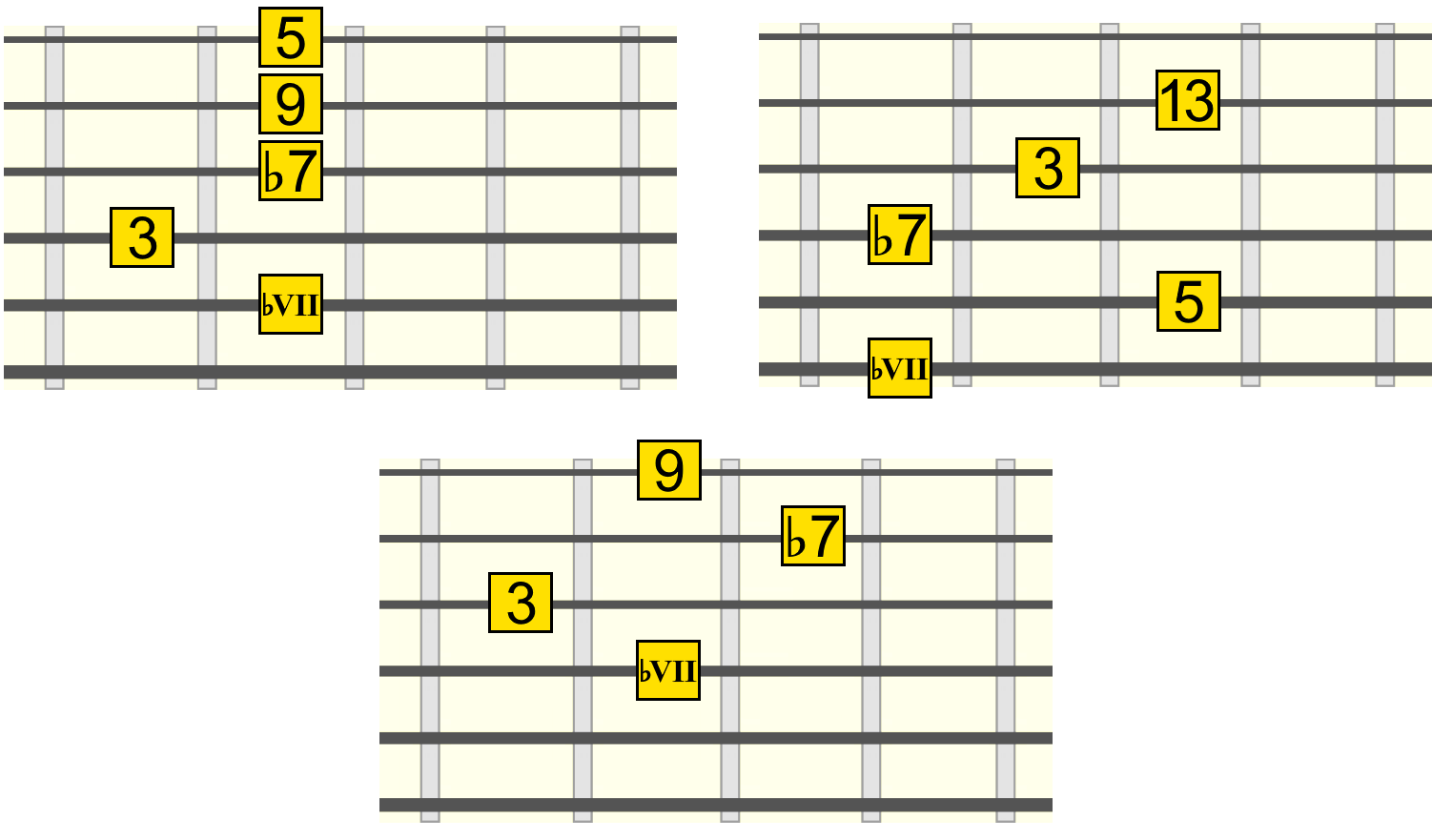

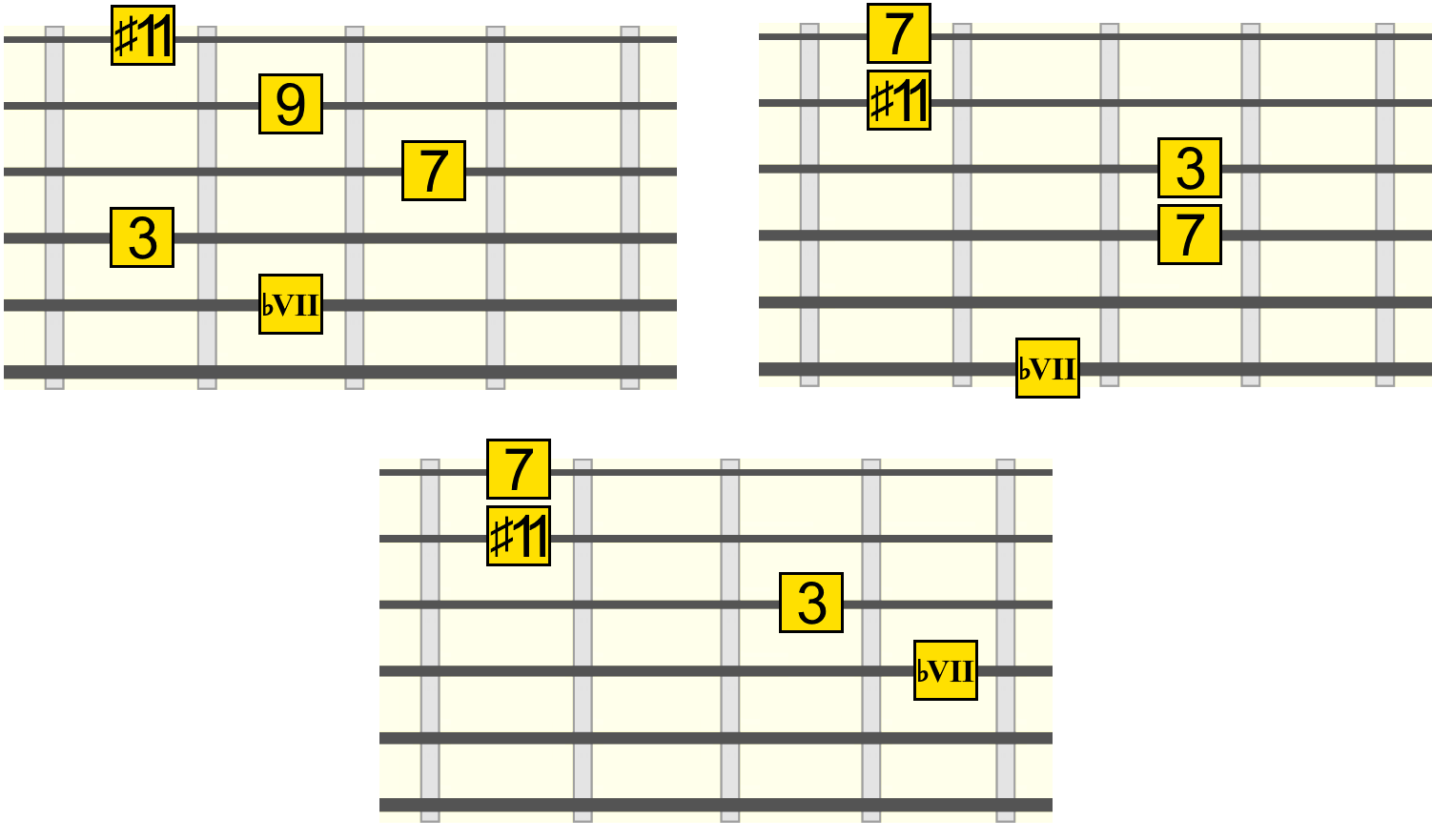

The subtonic is especially versatile in terms of chord quality. A regular dominant seventh (for a bluesier sound) or major seventh (for a more soulful sound) will work well. Some of my colour picks...

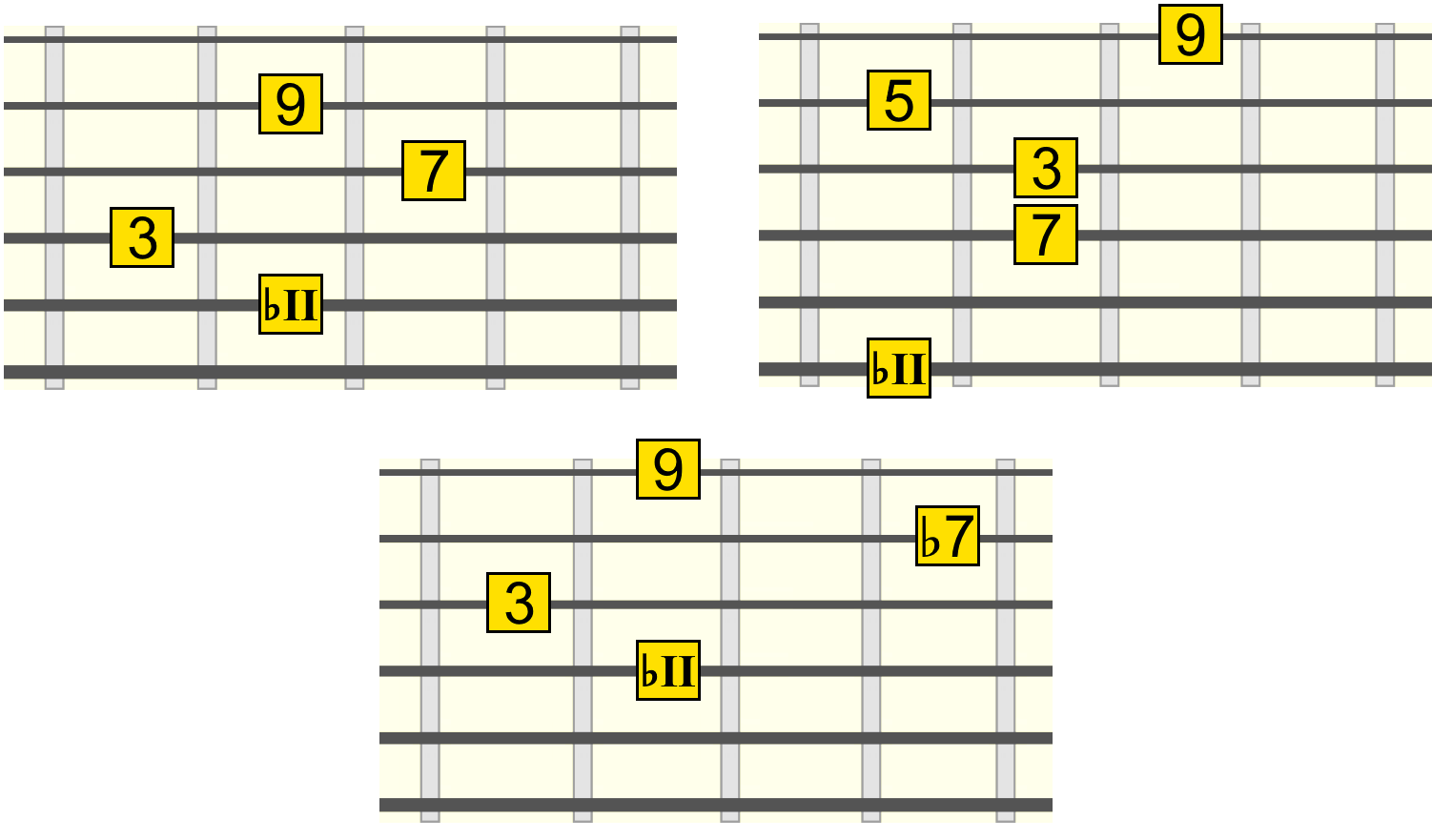

Dominant 9th/13th Shapes

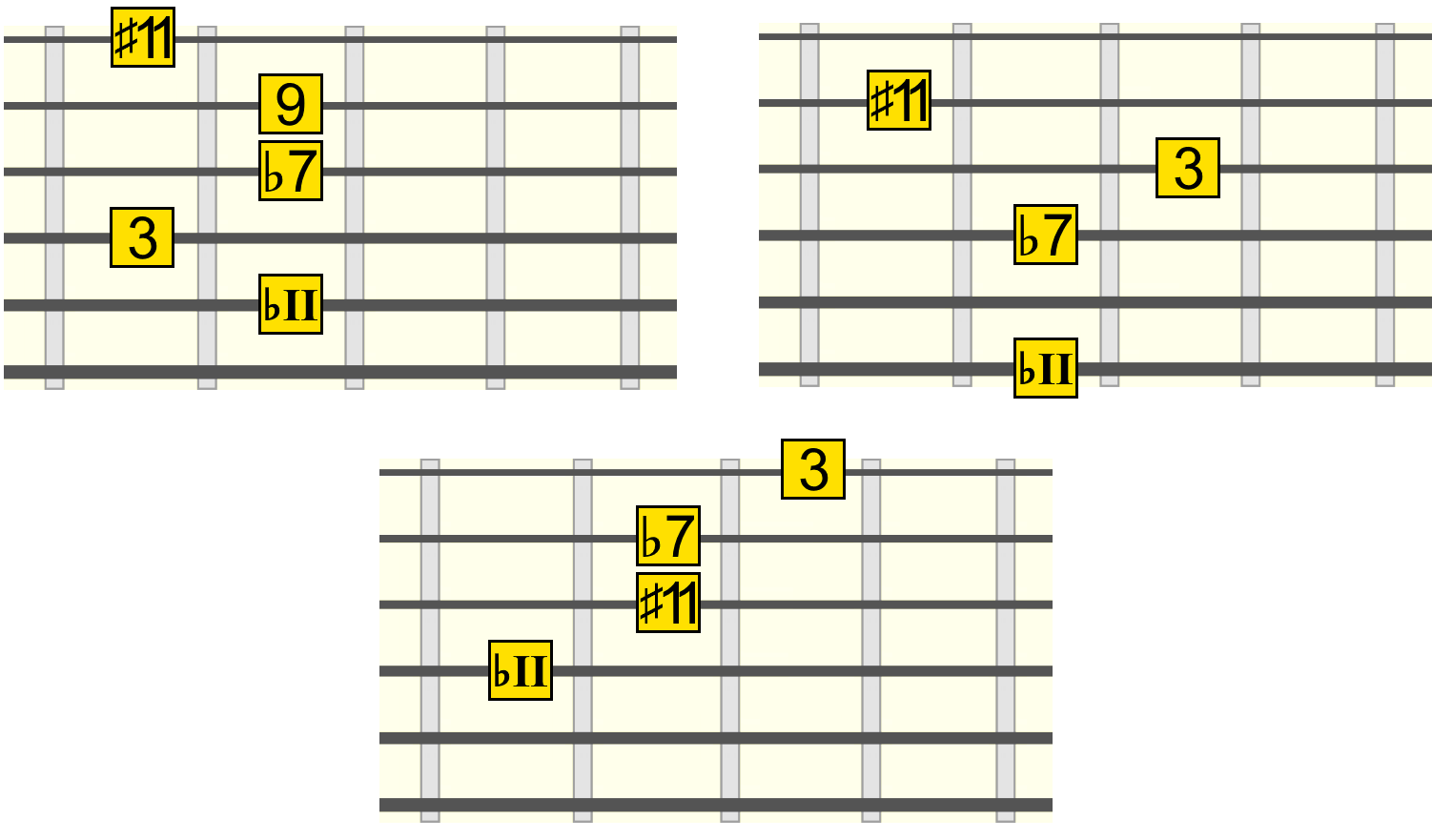

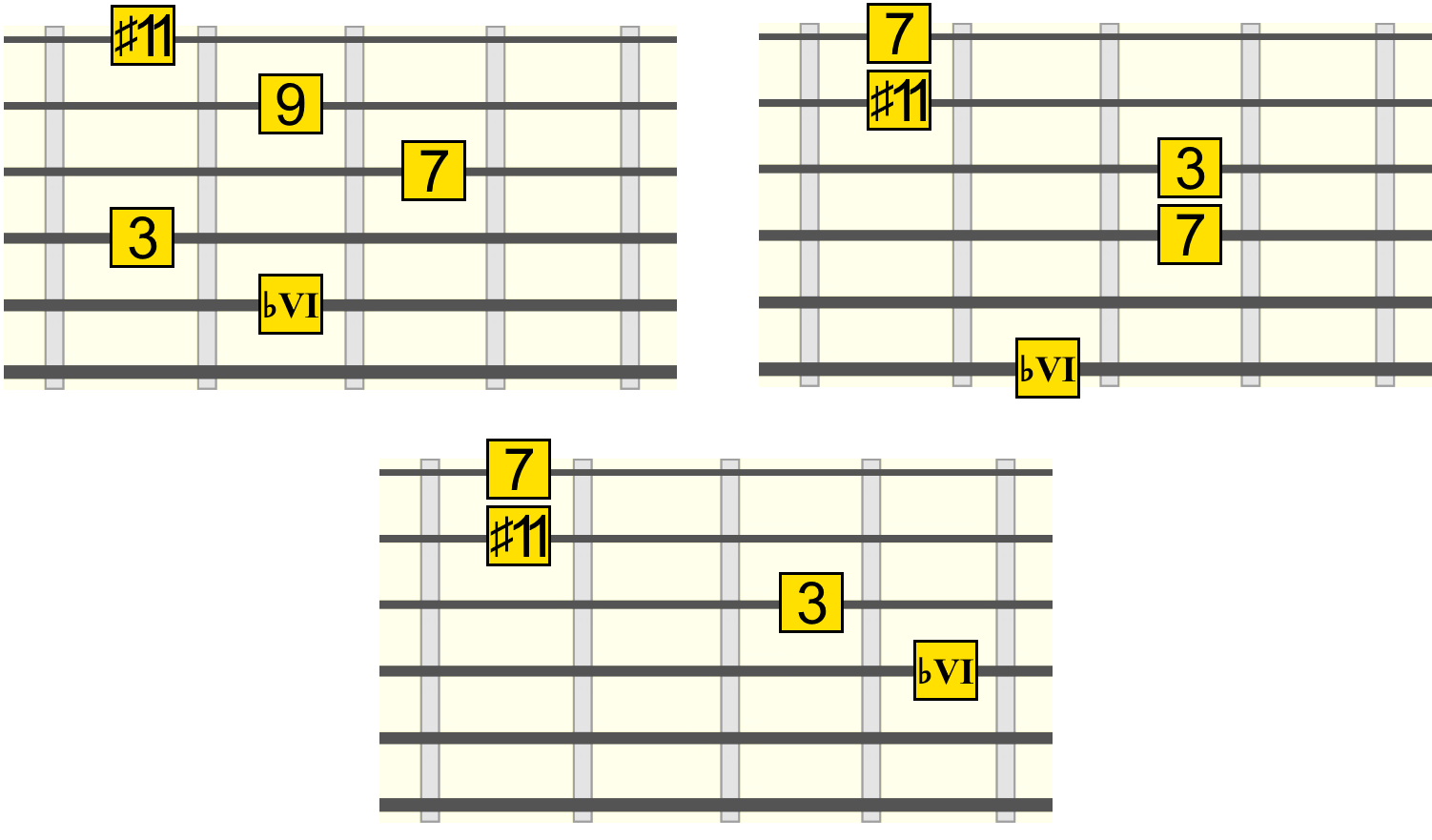

Dominant Augmented 11th Shapes

The augmented 11th (♯11) is an altered extension that sounds natural on this degree, evoking the Lydian Dominant scale.

Major 9th Shapes

Major Augmented 11th Shapes

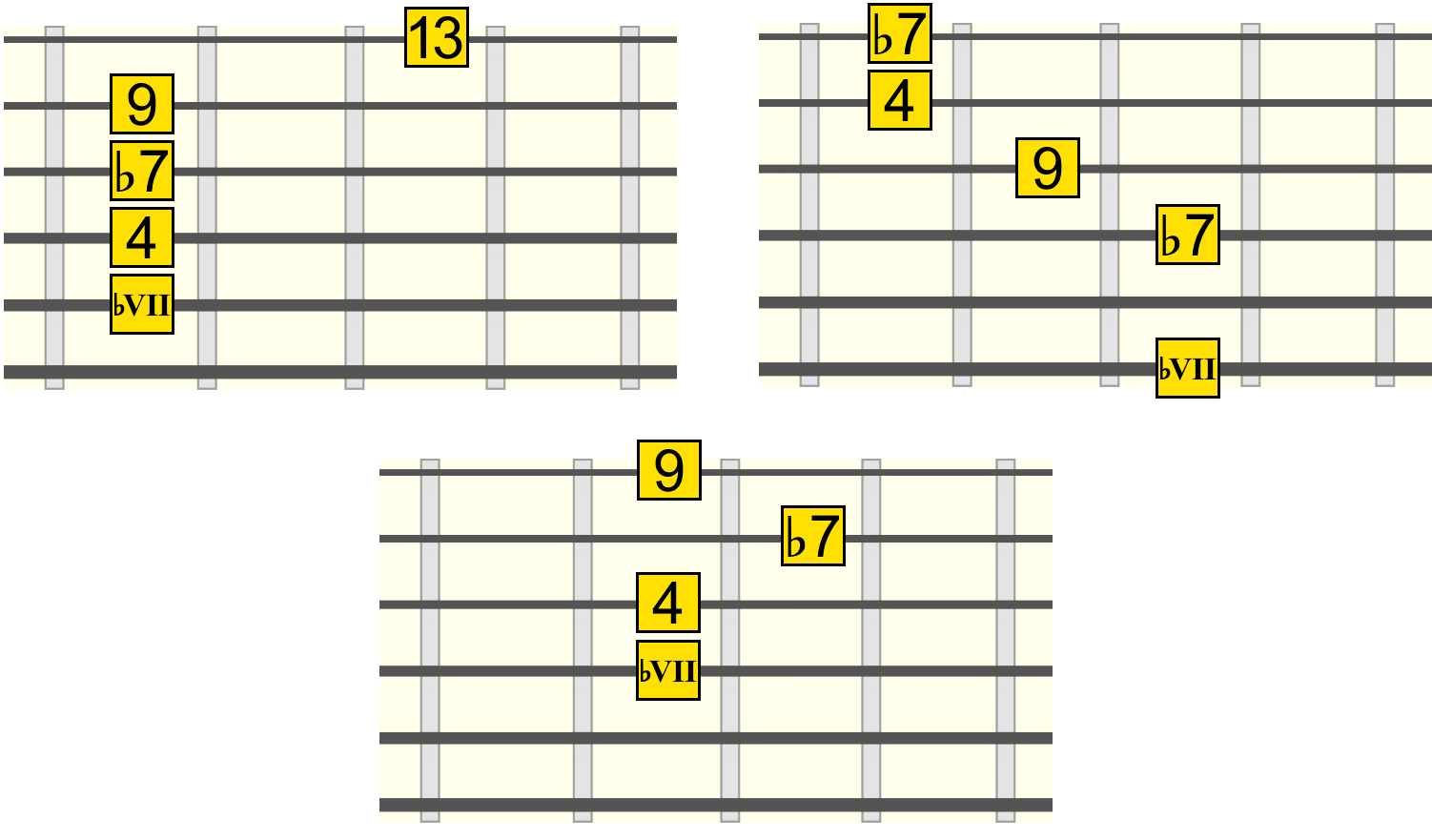

Suspended 9th/13th Shapes

Similar to how suspended 4th chords sound great on the dominant position, they also function very naturally on the subtonic approach to the tonic...

Tip: Remember that all these chords can be used anywhere in a progression (e.g. they don't have to precede the tonic). We're just becoming more conscious of the more varied "tonic approach" options we have.

The ♭II

A favourite dominant substitution among jazz musicians. It's often referred to as a "tritone substitution", the tritone being three whole steps from the dominant (e.g. G - tritone - D♭7 in the key of C).

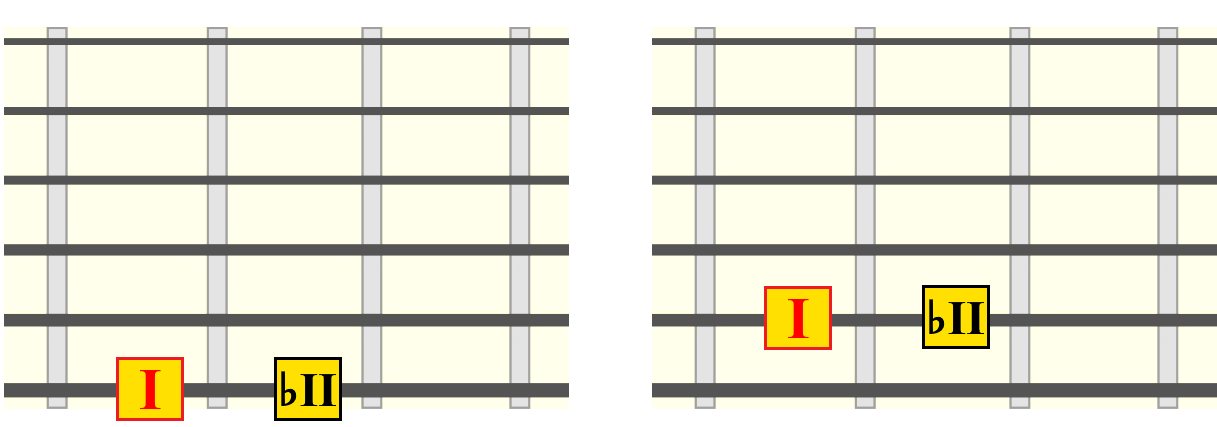

Visually, it's simply one semitone (or fret) up from the tonic, meaning it has a collapsing resolution that is more emphasised than the natural dominant.

For example, if we replace a regular ii - V - I cadence with a ii - ♭II - I, we can hear this substitution in its element. Key of G for these examples...

G / C / Am / D (I / IV / ii / V)

G / C / Am / A♭ (I / IV / ii / ♭II)

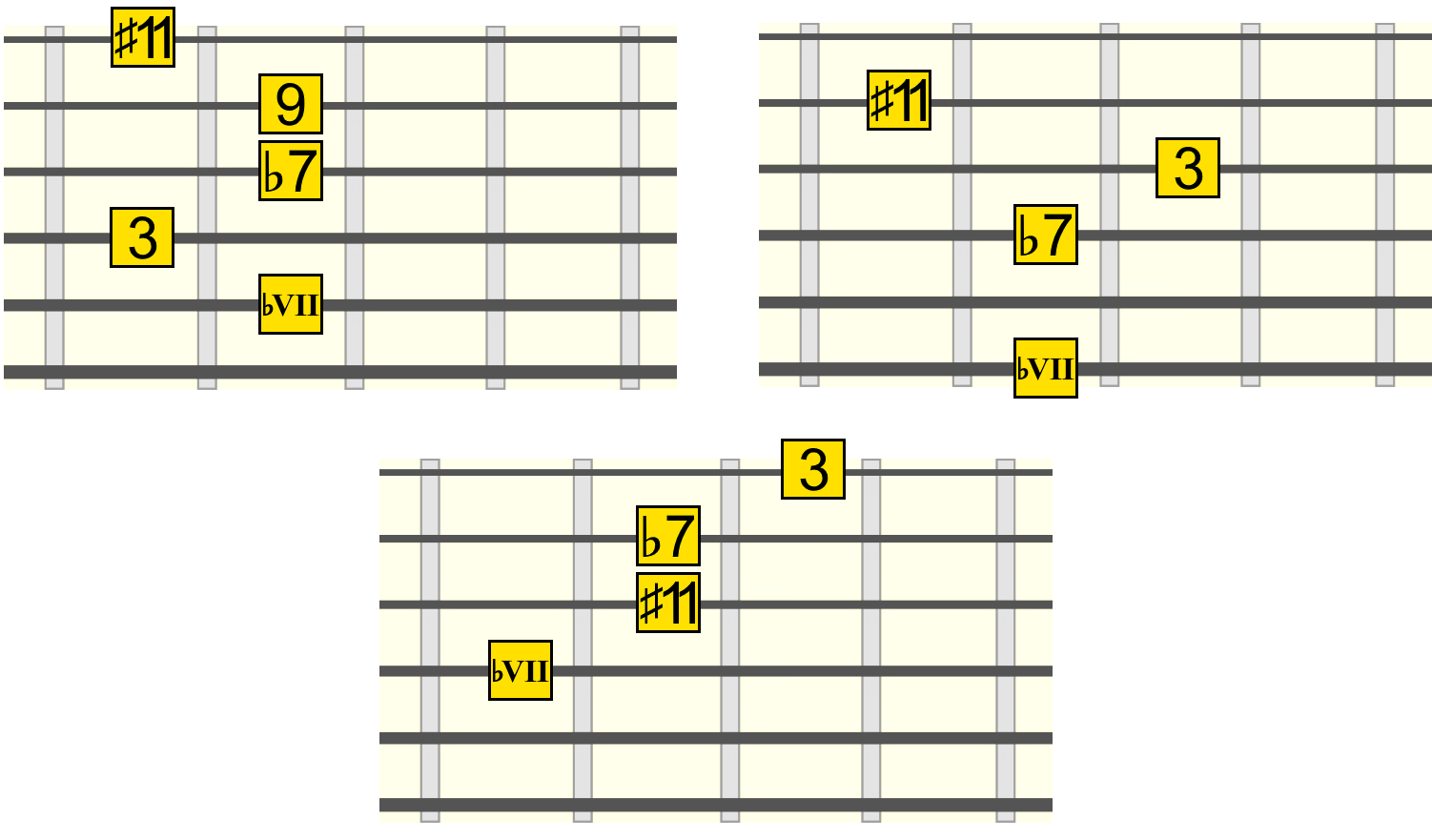

The dominant tritone substitution could be a whole lesson in of itself. But in terms of pure functionality, we can use both dominant 7th and major 7th variations comfortably on this ♭II degree...

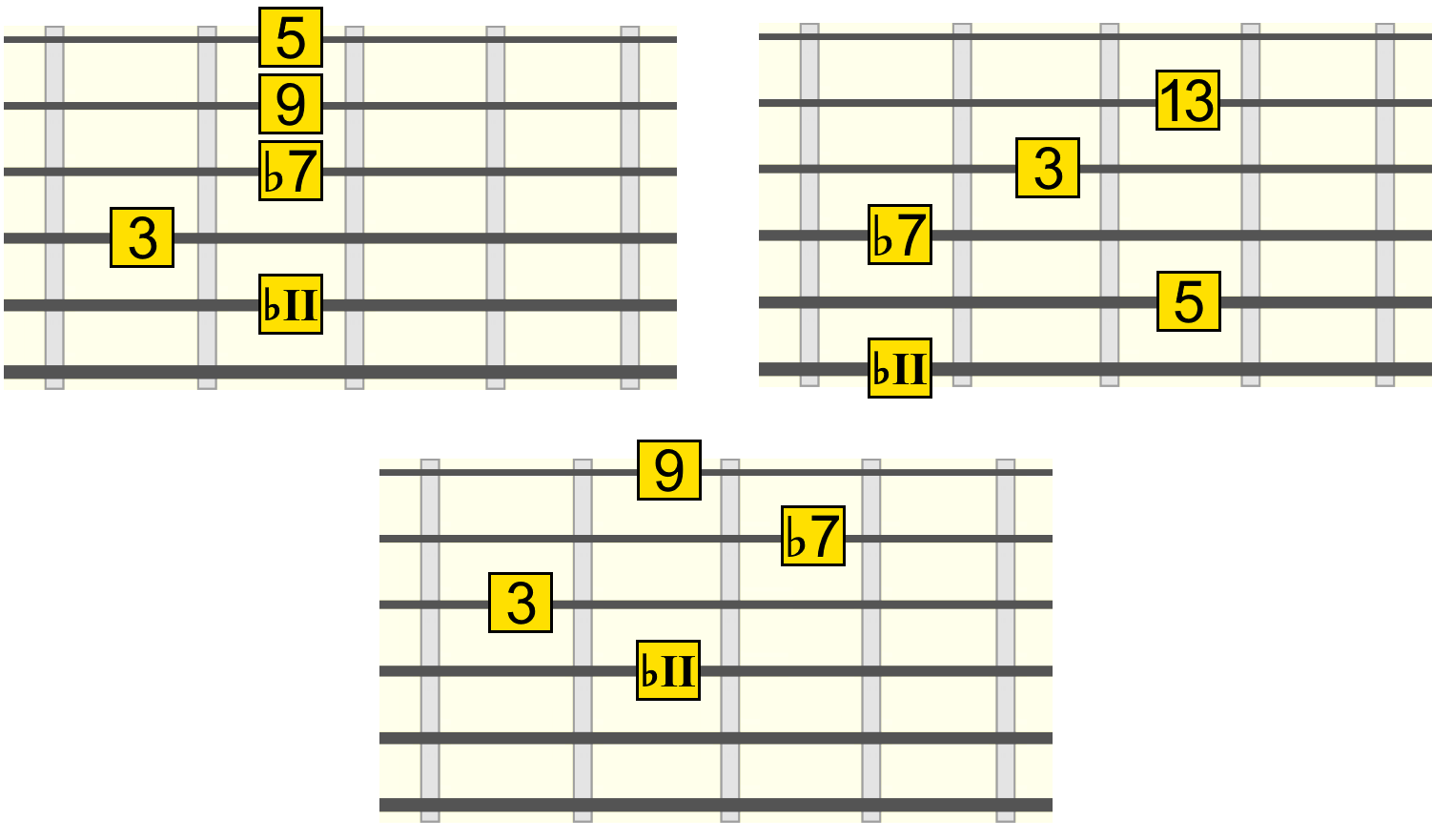

Dominant 9th/13th Shapes

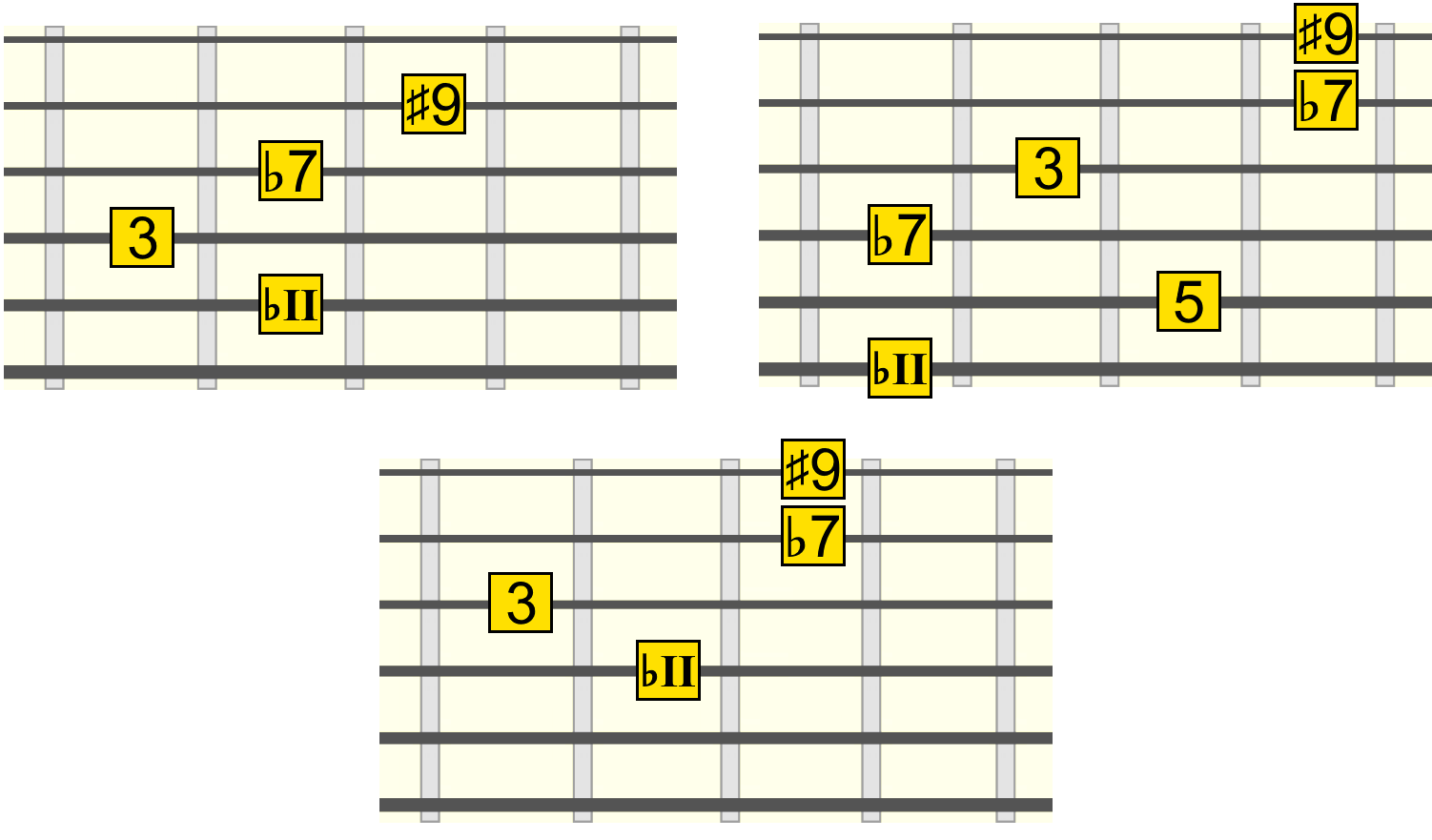

Dominant Augmented 9th Shapes

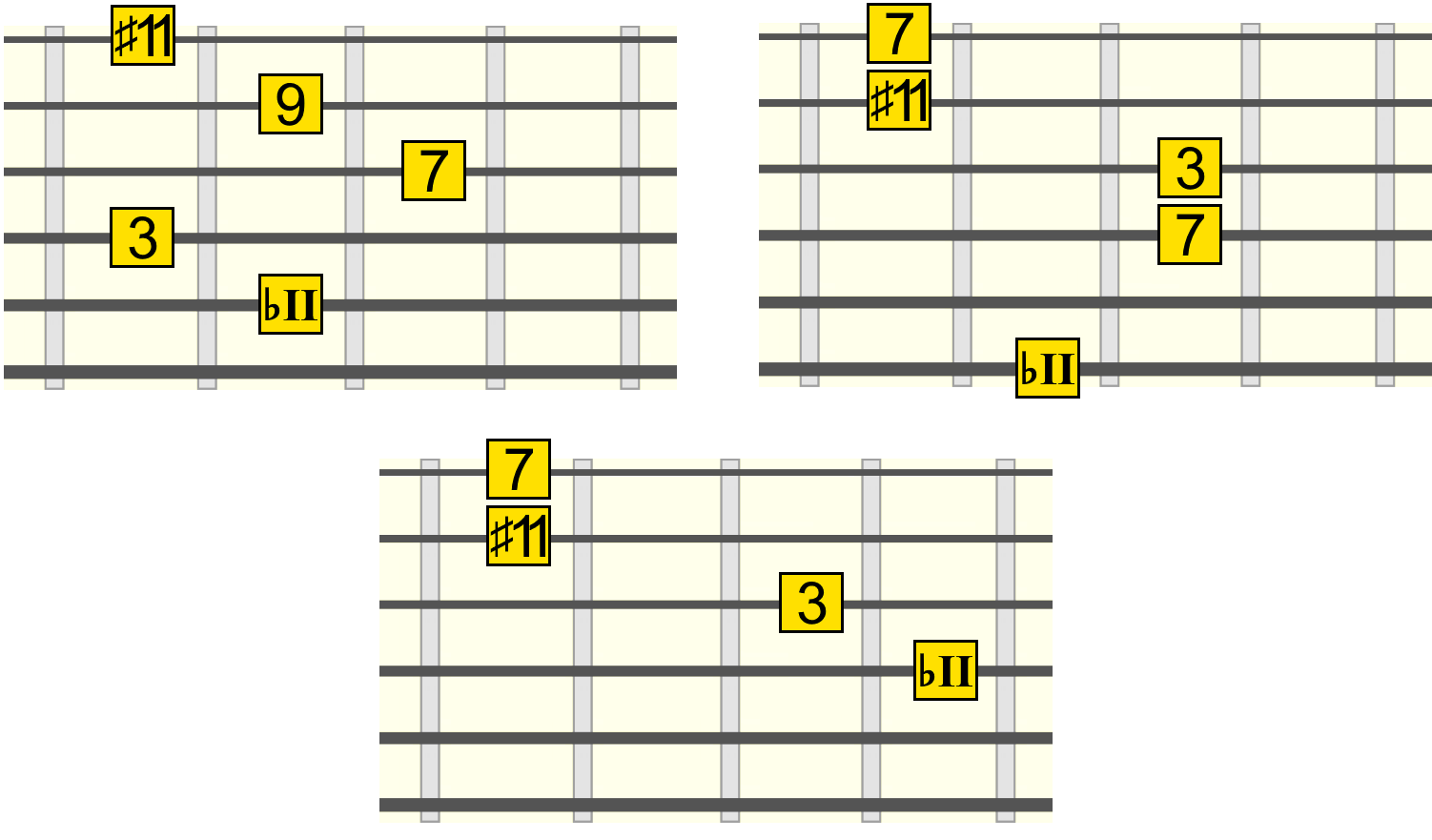

Dominant Augmented 11th Shapes

Major 9th Shapes

Major Augmented 11th Shapes

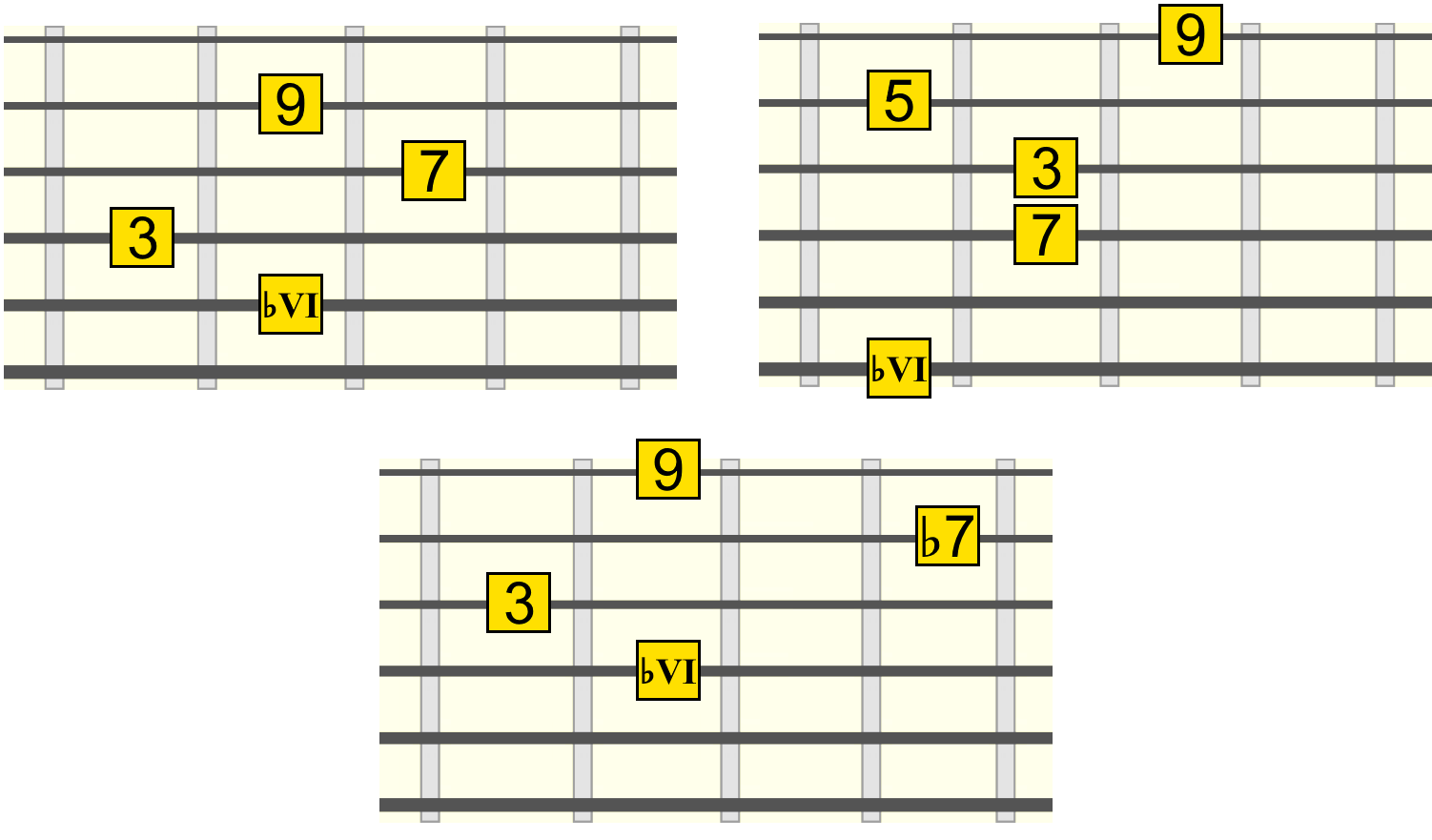

The ♭VI

I especially like the flat 6th (♭VI) degree, because it feels quite distant from the tonic, yet at the same time resolves quite naturally. It can be seen as "borrowed" from the parallel minor key.

It lies one semitone/fret up from the natural dominant (e.g. A♭ in the key of C). Because of this, you'll often hear it collapse down to the gravity of the dominant before resolving to the tonic (e.g. A♭ - G7 - C), kind of like an alternate ii - V - I.

However, we can take a more direct route. Take a listen to some examples in the key of A...

A / E / D / E (I / V / IV / V)

A / E / D / F (I / V / IV / ♭VI)

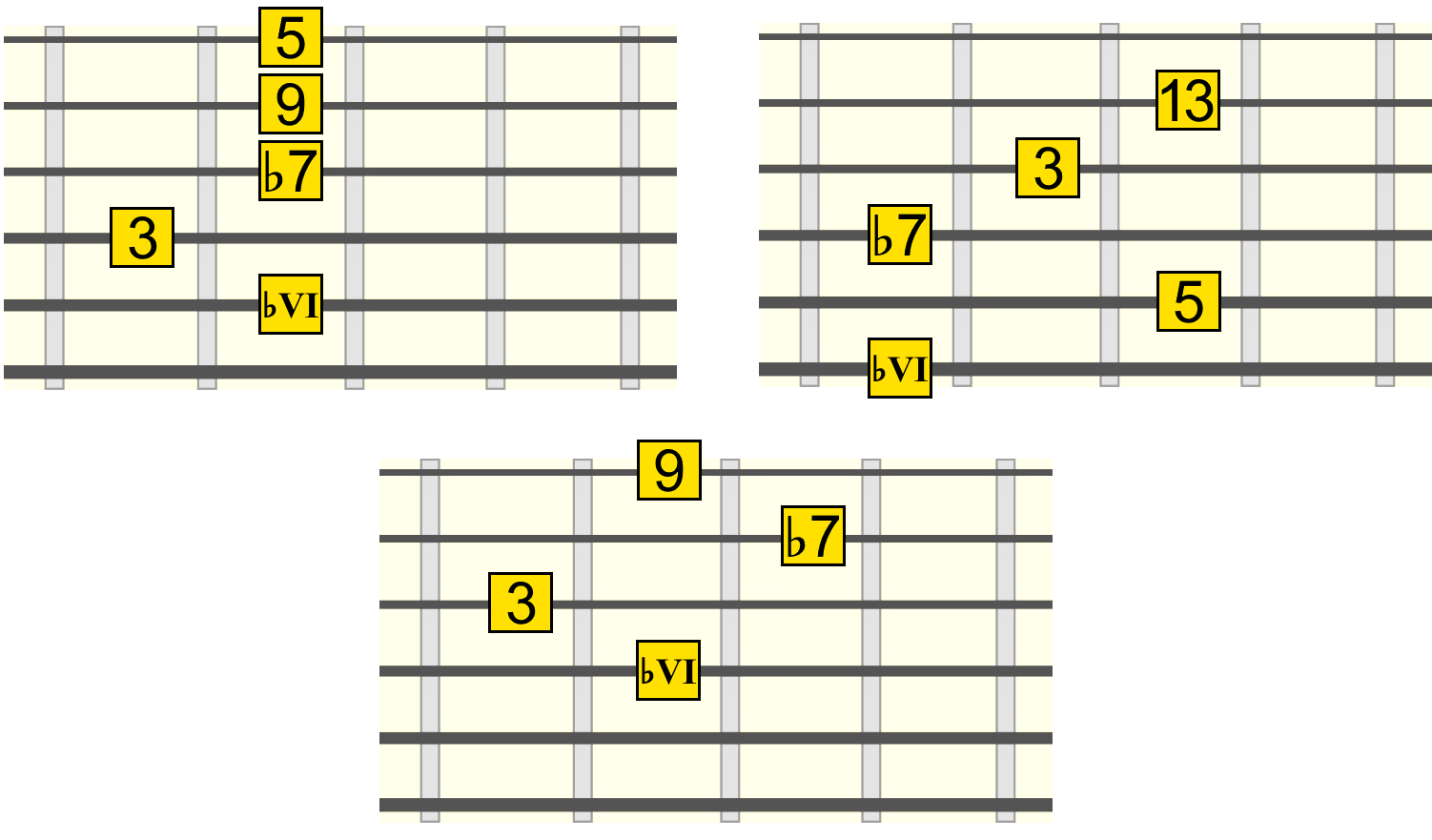

Like with the other substitute degrees, we have the option between a dominant 7th or major 7th based quality. But here are some more colourful variants...

Dominant 9th/13th Shapes

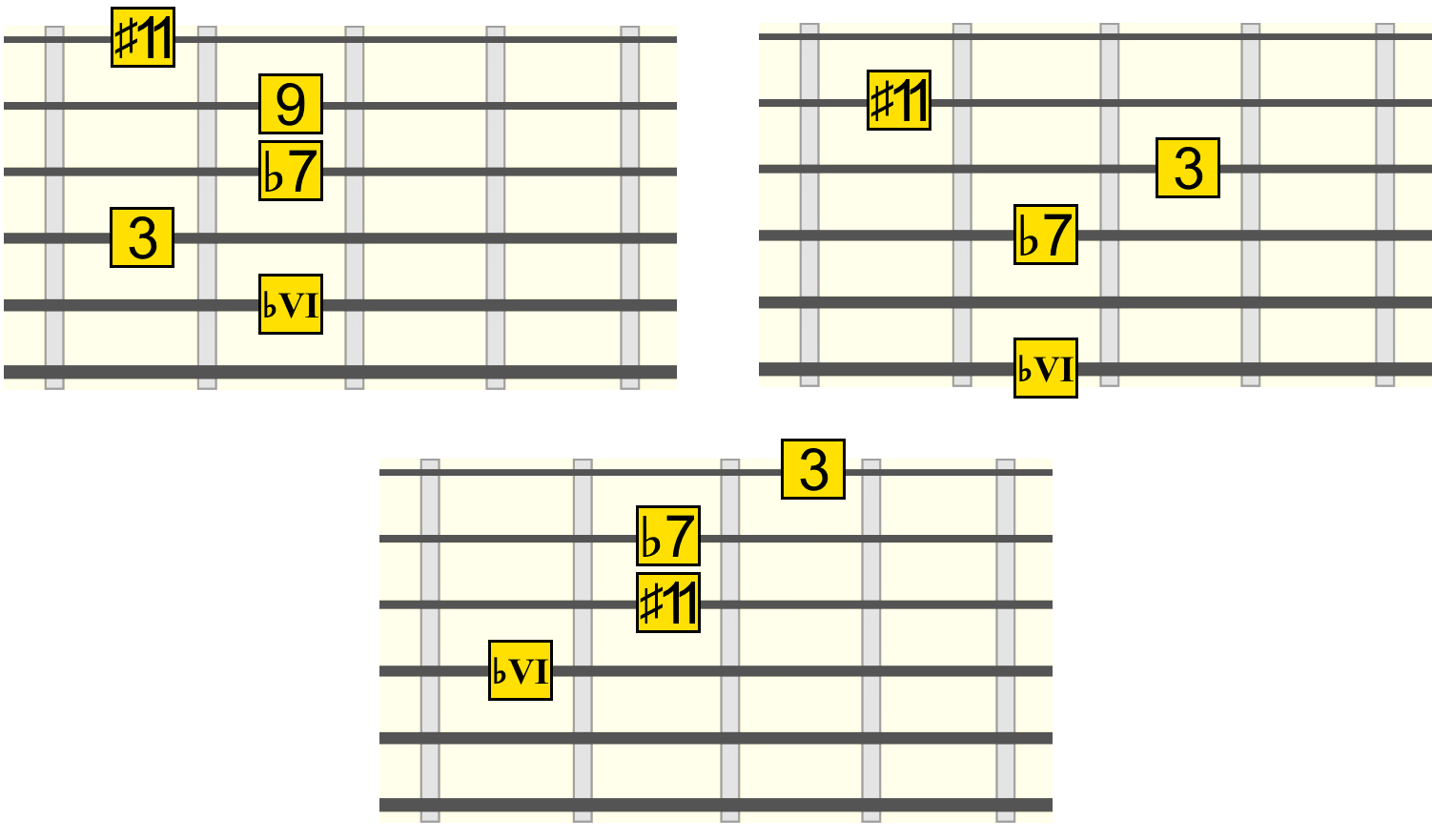

Dominant Augmented 11th Shapes

Major 9th Shapes

Major Augmented 11th Shapes

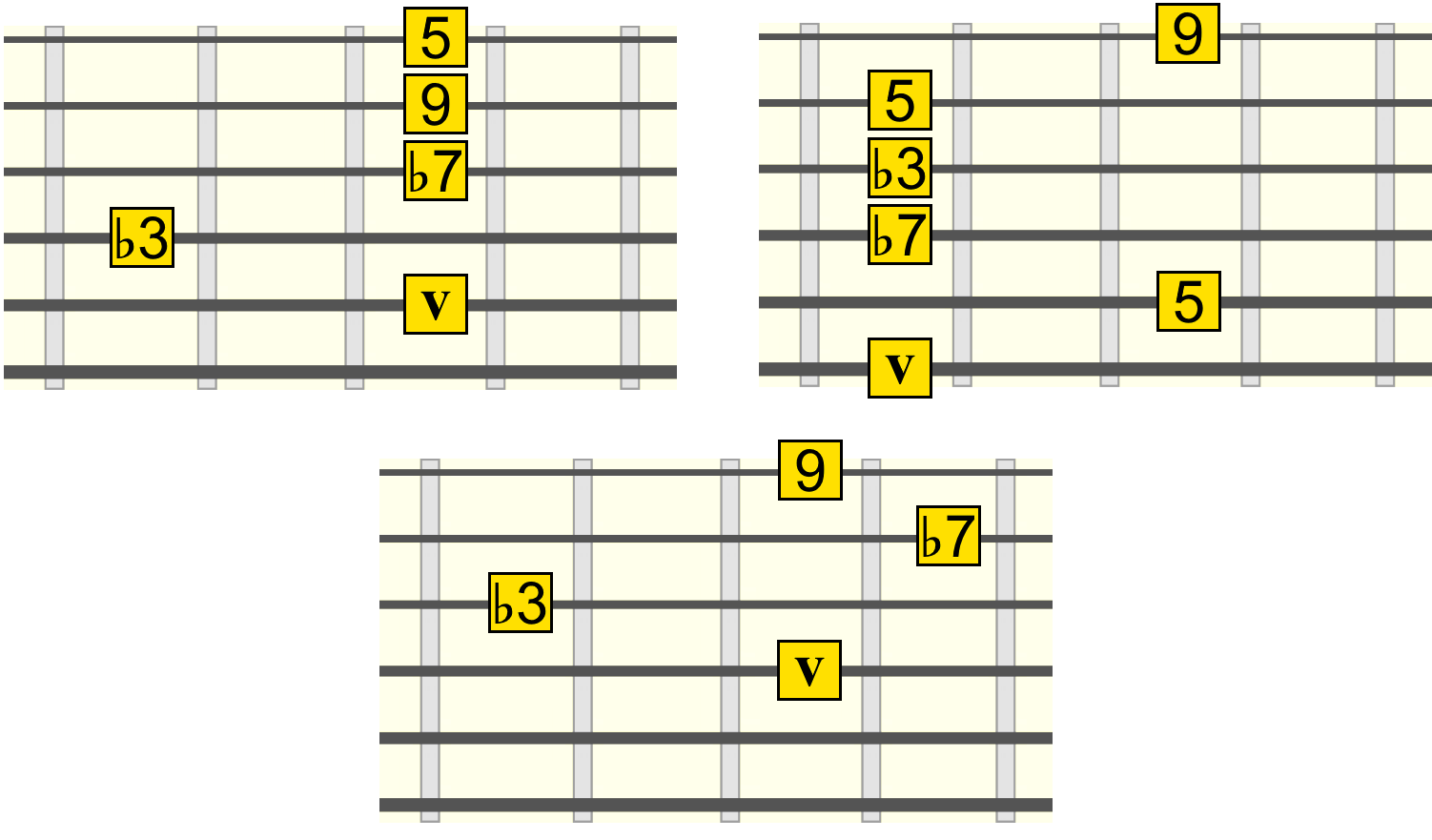

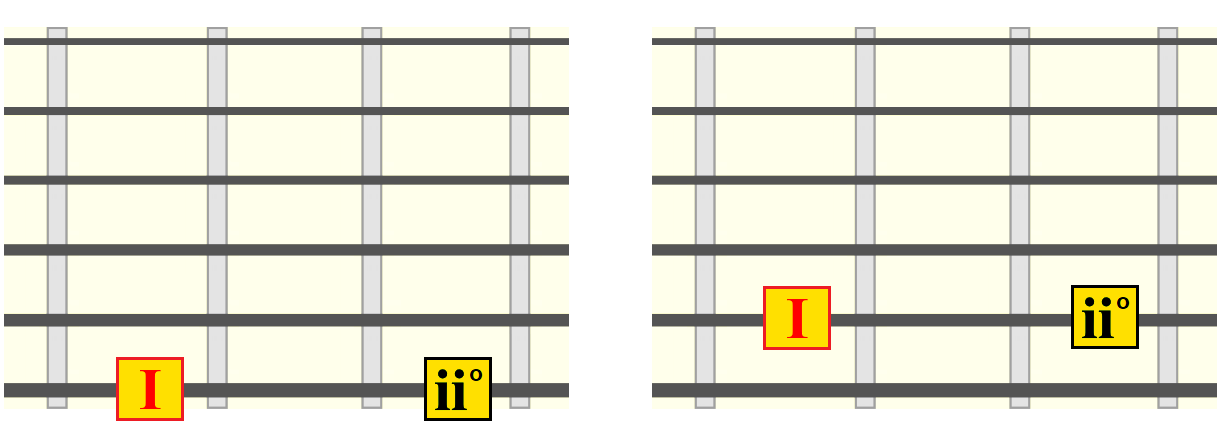

The iiᵒ (half diminished)

Technically this substitution is just an inversion of the dominant 9th "backdoor" ♭VII variant from earlier. But when given a firm bass root on that second degree (one whole step up from the tonic, also called the supertonic), we get a very beautiful, yet melancholic sound that is more reminiscent of the minor iv.

That would make sense, because this "half diminished" or m7♭5 chord is also an inversion of the minor 6th chord on the 4th (iv) degree!

But aside from the intrinsic connection between these three chords (which would involve a whole lesson in of itself), let's take a listen to the approach to the tonic this diminished iiᵒ chord offers us as a dominant substitution, in the key of B...

B / G♯m / E / F♯ (I / vi / IV / V)

B / G♯m / E / C♯m7♭5 (I / vi / IV / iiᵒ)

The iiᵒ can be seen as a whole step (two frets) up from the tonic (see the above diagram). Here are the most common shapes...

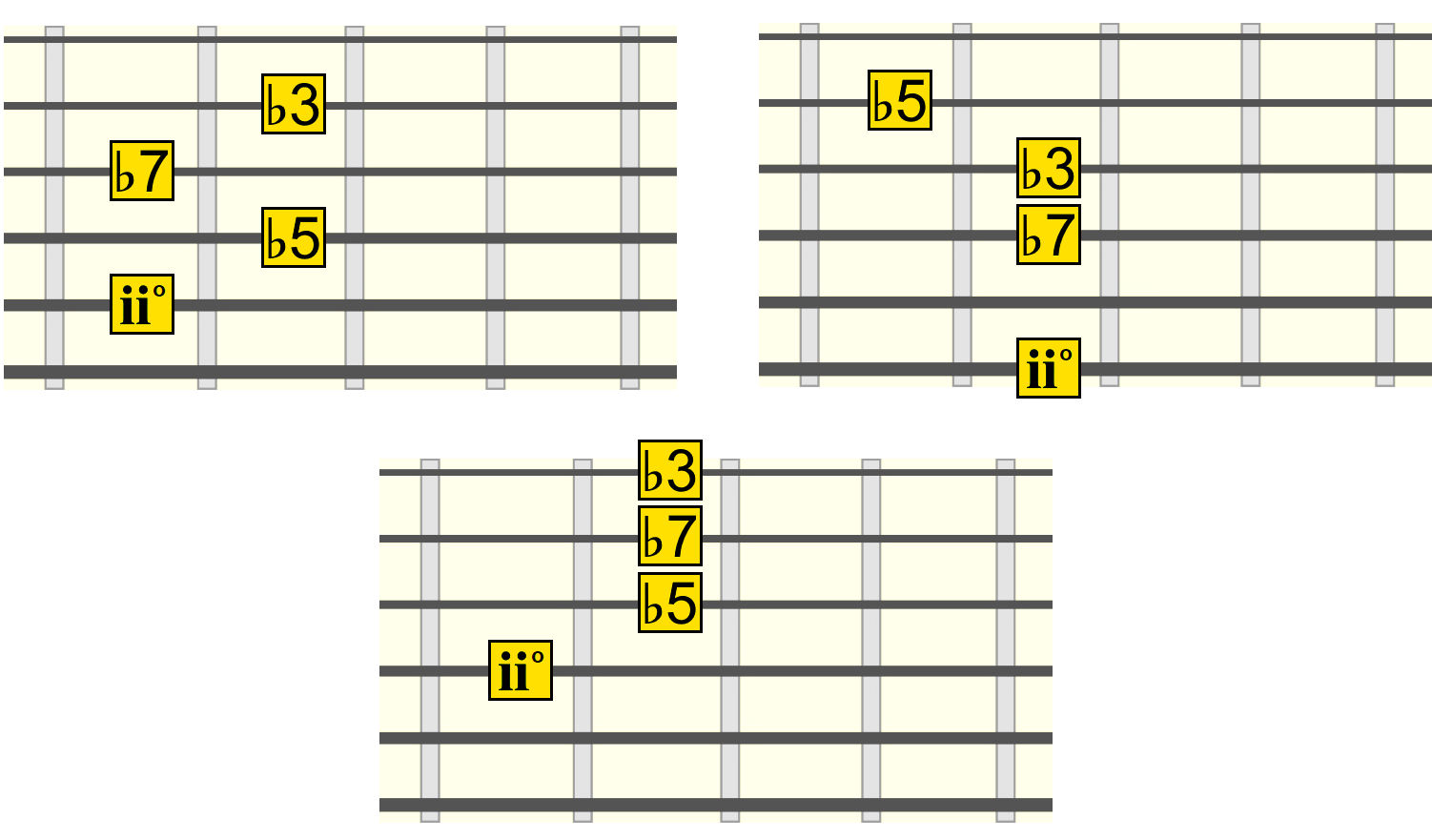

Minor 7th, Diminished 5th Shapes

Slash Chords

Slash chords, also known as altered bass chords, are when the bass is on a chord tone other than the root. For example Fm/G or "Fm over G" would indicate an F minor triad over a G bass. This changes the expression of the voicing and can allow for more variation and tension.

Even if the bass is on the dominant, we can still play chords in substitute positions over it. Often we'll just have to focus on the upper tones of the chord so as not to muddy the harmony too much.

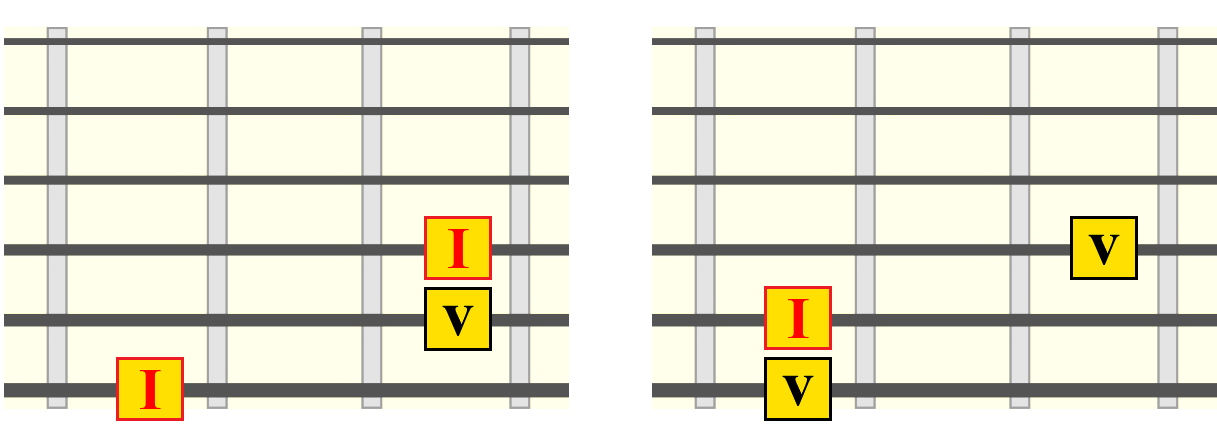

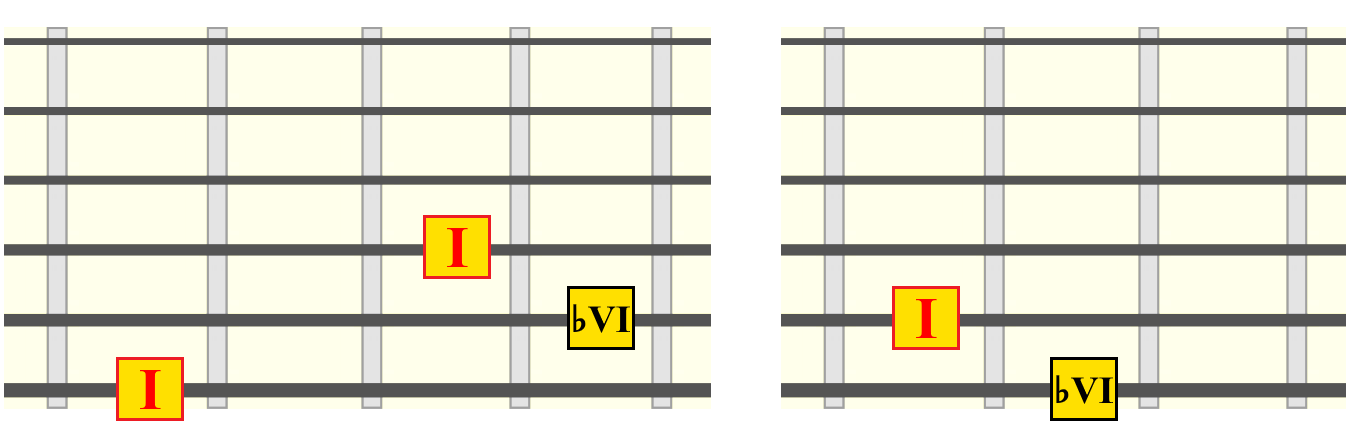

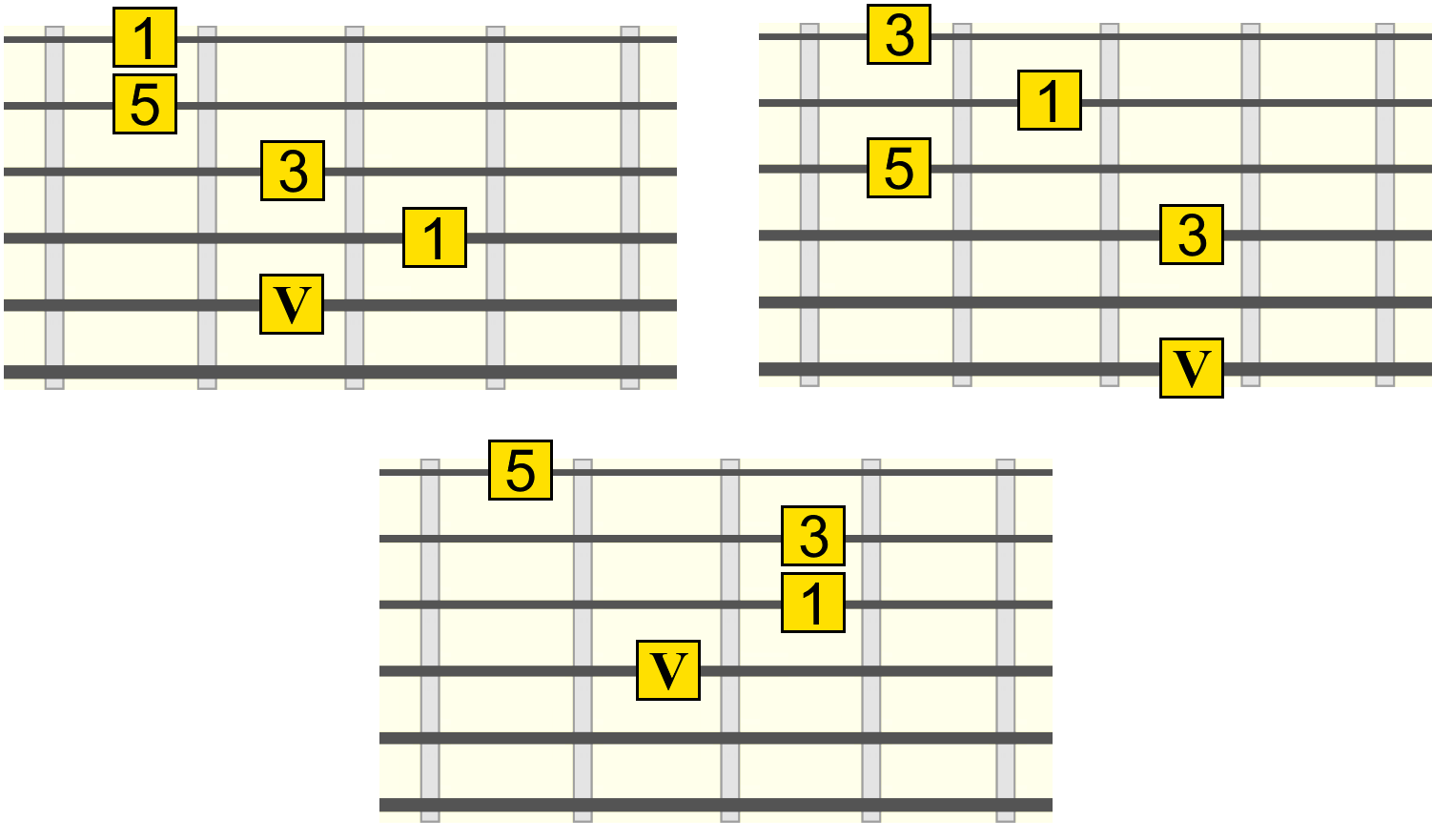

Let's take the bass on the V position (e.g. G in the key of C major). I've provided the V - I root string positions again for reference...

IV / V

Example in C major - C / Am / F / F/G

This can also be seen as playing Vsus9 (i.e. a suspended dominant). However, seeing it as playing the IV (upper triad) over a V bass (e.g. F major over G, or F/G) allows us to play the IV triad in any neck position over the bass to give us that suspended dominant sound.

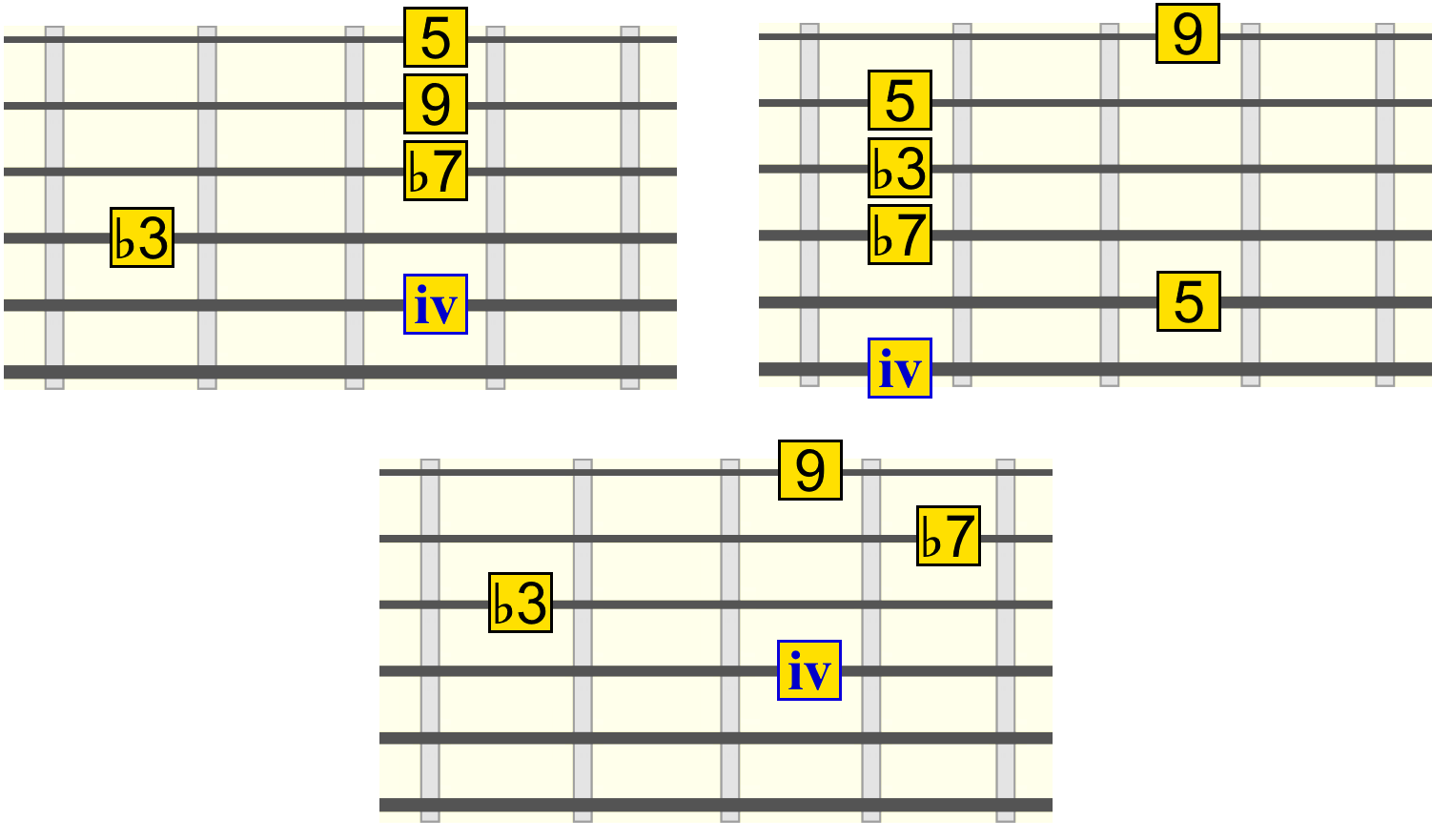

Remember, the upper, three-string triad intervals labelled below are that of the substitute triad...

iv / V

Example in D major - D / G / Em / Gm/A

Here we play a minor iv (upper) triad over the V bass (e.g. Fm over G or Fm/G), giving us a mixture of that strong dominant bass, but with a hint of the more melancholy iv...

♭II / V

Example in E major - E / G♯m / F♯m / F/B

Here we play a ♭II (major) triad over the V (e.g. D♭/G in the key of C major). The V bass really brings out the tritone sound in a striking way, yet the triad structure still resolves comfortably down to the tonic.

Remember, you can use any three-string triad position for this ♭II. So as long as the bass is covered, you're free to place or roam through its inversions...

♭VI / V

Example in G major - G / D / Em / E♭/G

Here we take the ♭VII major triad and place it over a V bass (e.g. A♭/G). Again, compared to the root position from earlier, it sounds more "outside" of conventional harmony, but we might sometimes want that sound for a more impactful resolution...

Hopefully you can hear how keeping that bass on the dominant root adds to the anticipation of a resolution to the related tonic (especially when part of a larger progression).

So if you're accompanying a track or jamming, and the bass goes to the dominant, just be aware that you can still substitute with shapes outside of the dominant position, such as those outlined above.

Final Notes

What we have here are effective options for creating alternative tonic approaches to the standard dominant. I've by no means exhausted the options, but these should get you started and train your ears to some "tried and tested" dominant substitutions heard in music, and that you may want to try yourself.

The dominant has a very versatile function and we can even change its natural degree, or build substitutions on that bass degree, to modify its character. As we've seen (and heard), the approach to the tonic can come from various directions and "outside" places.

The key is in knowing what these options sound like and how to visualise them on the neck, so we can jump to them without unnecessary trial and error interrupting that process.

If you enjoyed exploring the ideas in this lesson, you may also enjoy my lesson on substitutions using diminished 7th chords.