Jump to...

Extended Shapes | Progressions | Substitution | Reharmonisation | Modulation

Extended Minor Chords

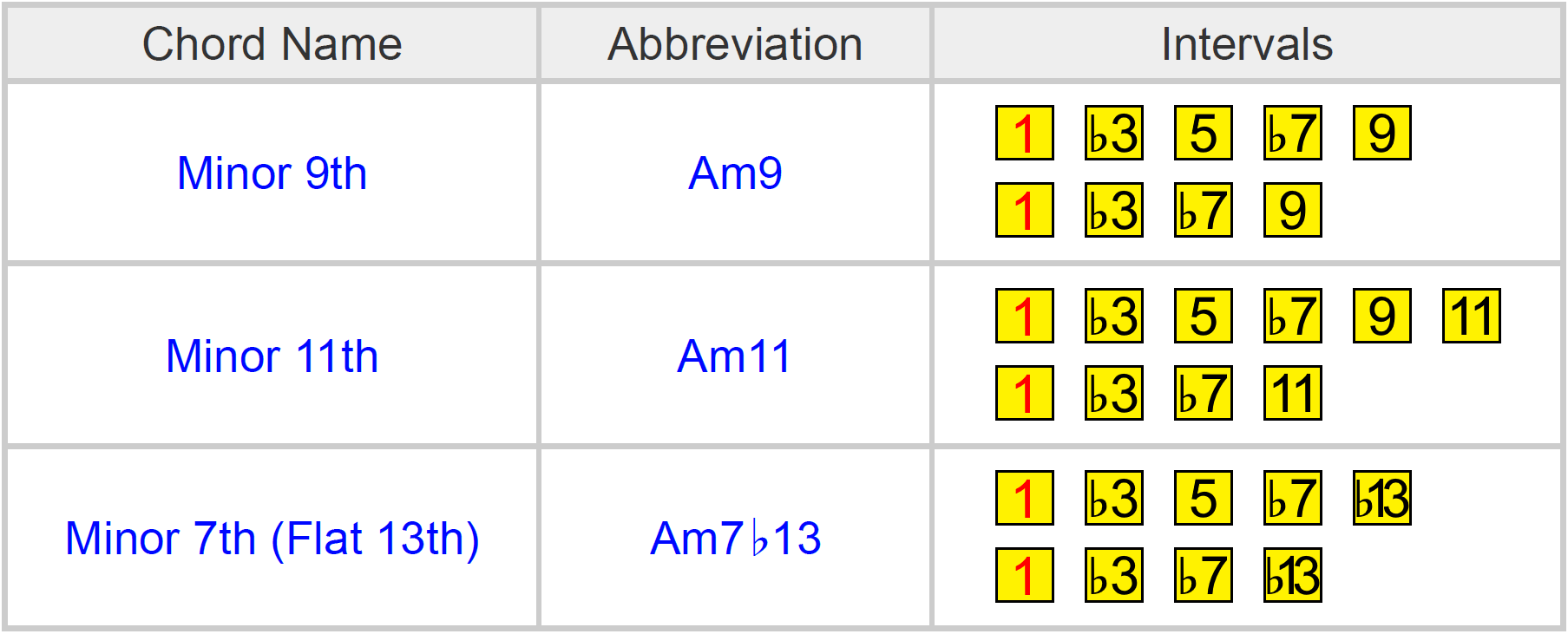

In this lesson we'll focus on three forms of minor chord extension - minor 9th, minor 11th, and minor 7th flat 13th.

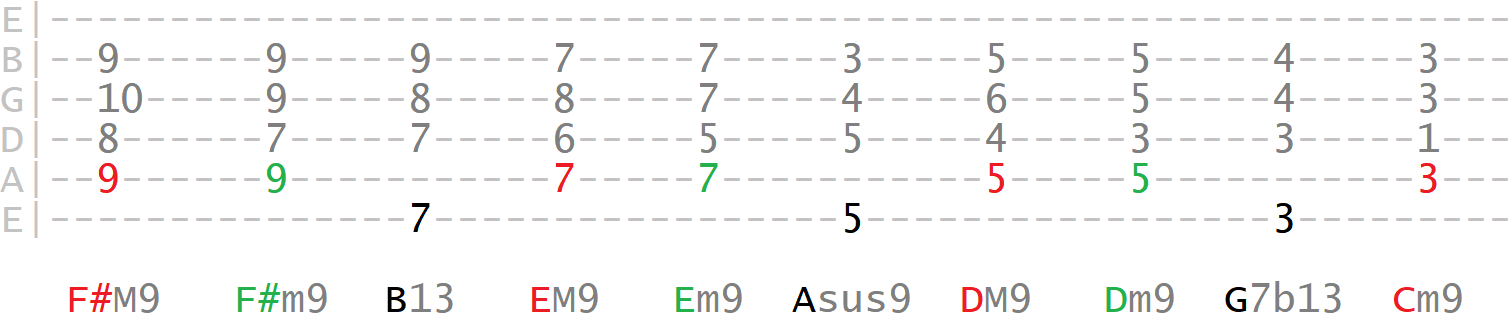

The table below shows the interval structure of these chords from the root. On guitar, we'll often omit certain tones in the full chord for fret hand economy, as shown in the second interval row for each chord...

Using these chords will give us more voicing options and give our progressions a more soulful colour.

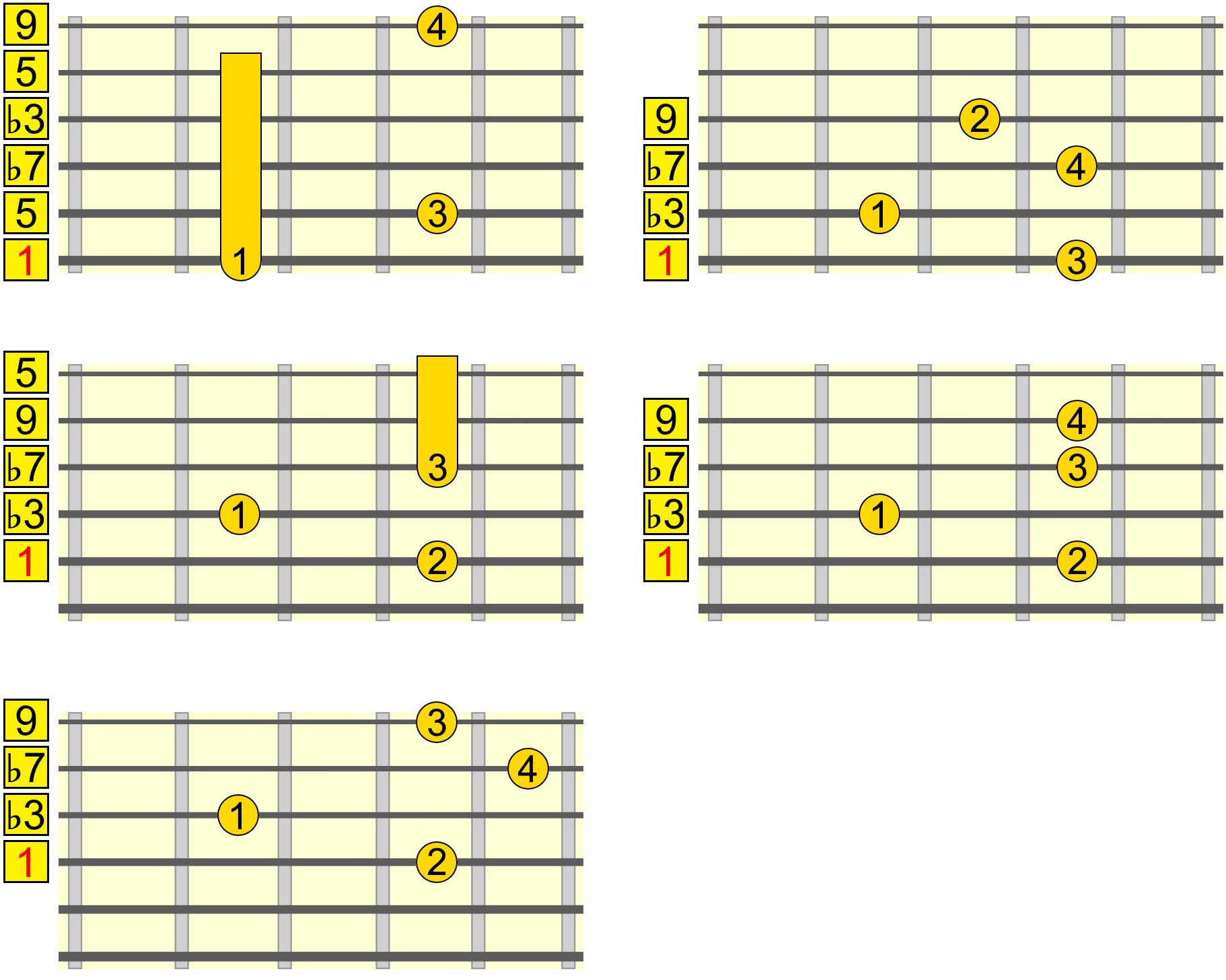

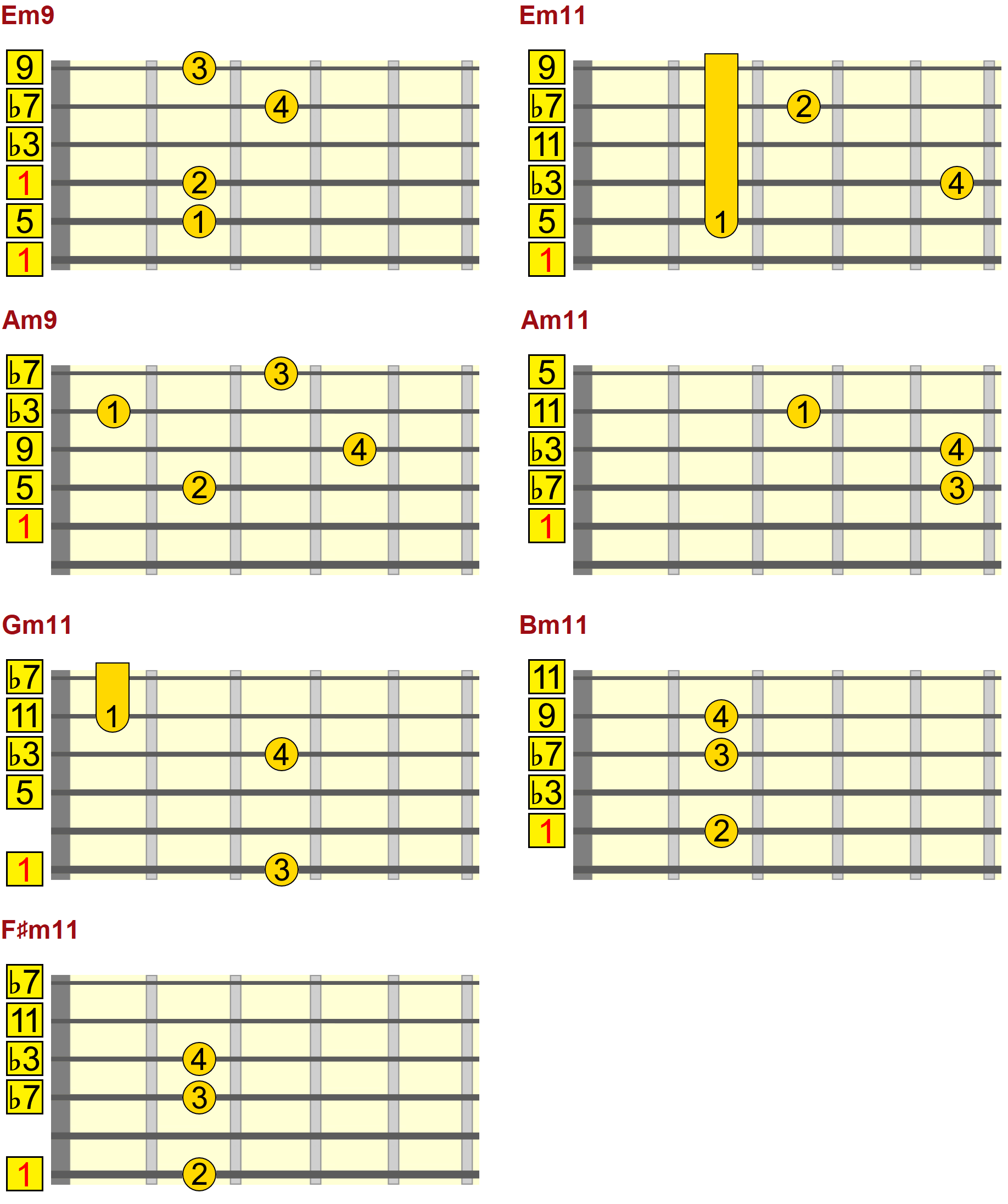

Movable Shapes

Let's begin by learning the movable (i.e. played at any fret position) shapes on different root strings (6th, 5th and 4th strings)...

Minor 9th Chord

The minor 9th chord (e.g. Am9) can be thought of as a minor 7th chord (1 ♭3 5 ♭7) with the added interval of a 9th (9). This extends the minor 7th sound, giving it more colour.

The interval provided by each string in the shape is labelled to the left of each diagram. It's not crucial that you learn the interval names. But it can be useful, in terms of ear training, to pay attention to how intervals, such as the 9th, add a particular colour to the chord...

Here I'm playing through the shapes in the order shown (note that I'm playing them at different frets - remember they're movable)...

Tip: See if you can locate the fret I'm playing the above shapes at (start with the bass root). This can work as an effective ear-fretboard training exercise for finding chords that are being played by other musicians/band members. Answers below...

Am9 (5th fret) / C♯m9 (9th fret) / Dm9 (5th fret) / Cm9 (3rd fret) / Gm9 (5th fret)

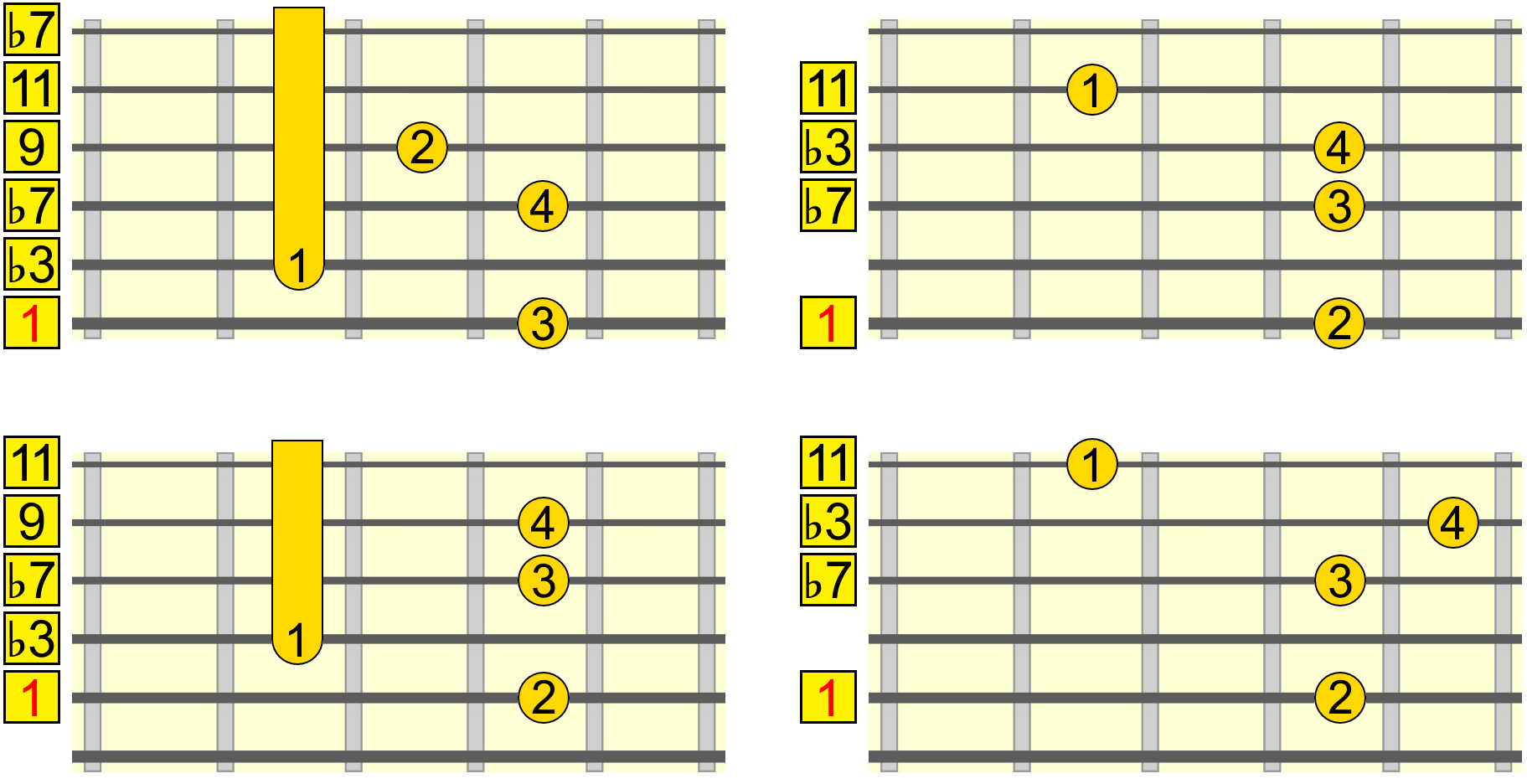

Minor 11th Chord

Minor 11th chords (e.g. Am11) can be thought of as adding the interval of an 11th to the minor 9th chord (1 ♭3 5 ♭7 9 11). However, sometimes we'll omit the 9th for both convenience and/or a slightly different sound...

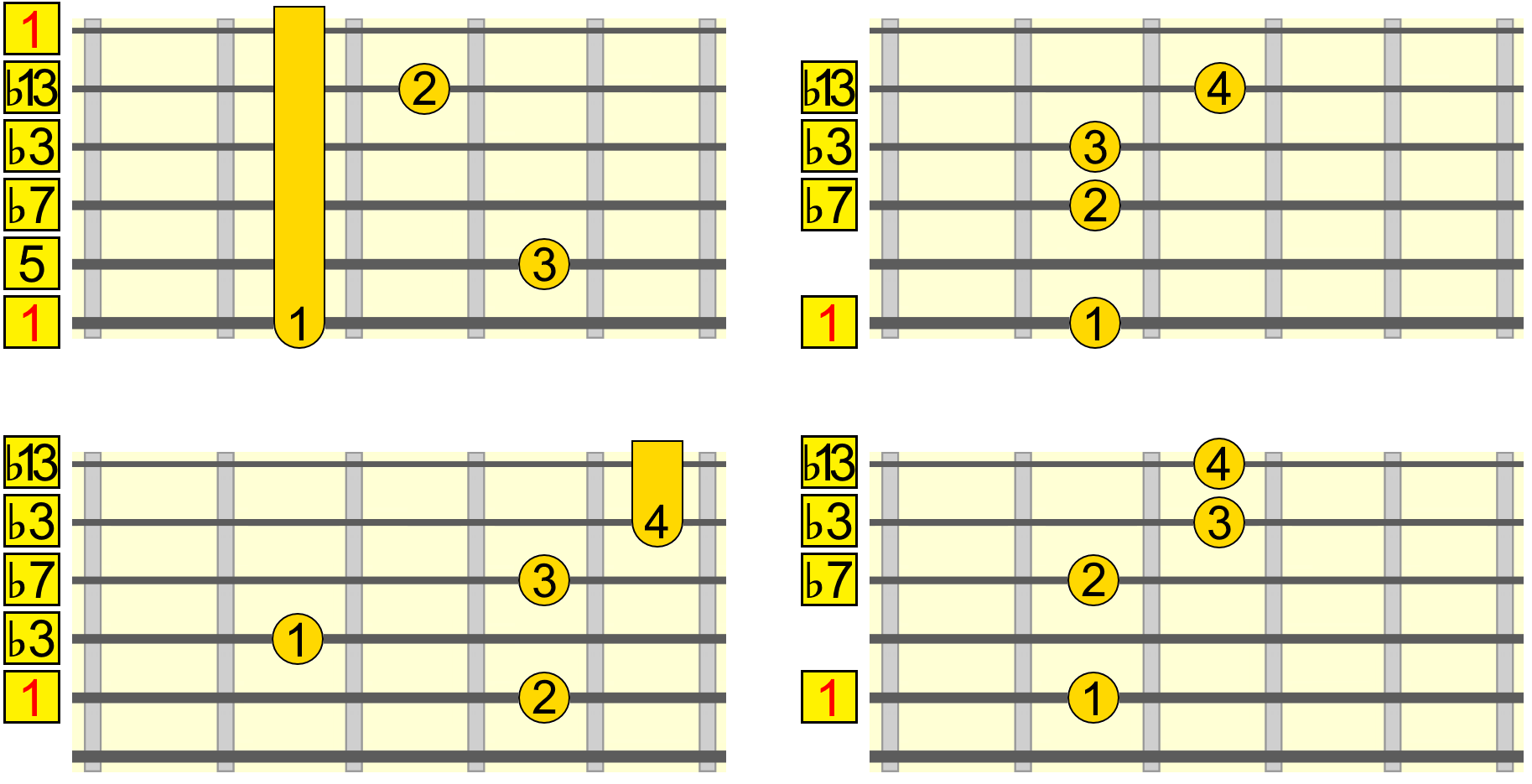

Minor 7th (Flat 13th) Chord

Played in isolation, this chord has a rather peculiar, some might say dissonant sound. But as with a lot of chords, and as we'll hear later, it's the context in which we use them that reveals their true quality and function.

Minor 7th flat 13th chords (e.g. Am7♭13), as the name implies, involve adding the ♭13 interval to the minor 7th chord (1 ♭3 5 ♭7 ♭13)...

Side note: The m7♭13 chord can be seen as an inversion of a major added 9th (e.g. Fadd9) or major 9th (e.g. Fmaj9) chord, depending on the context in which it's used. However, we'll use m7b13 as the reference name of these shapes for the purpose of this lesson.

Open Position Shapes

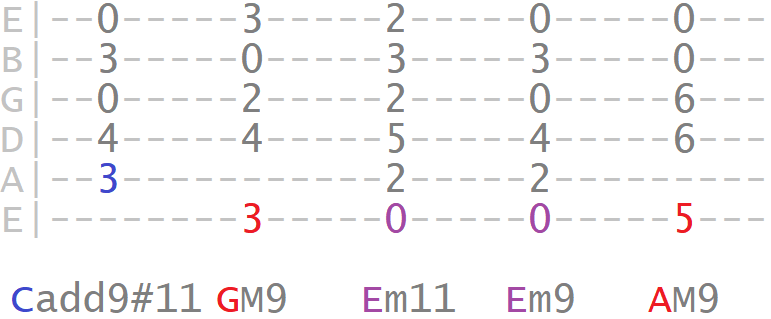

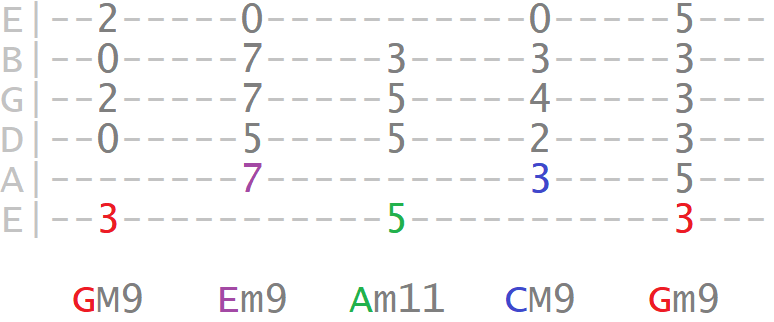

We can also play minor 9th and 11th chords in open positions (i.e. shapes that include open, unfretted strings). These offer vibrant alternatives to the standard minor open position chords we learn as beginners.

In the diagrams below, the nut is represented by the thick grey bar, followed by the first five frets...

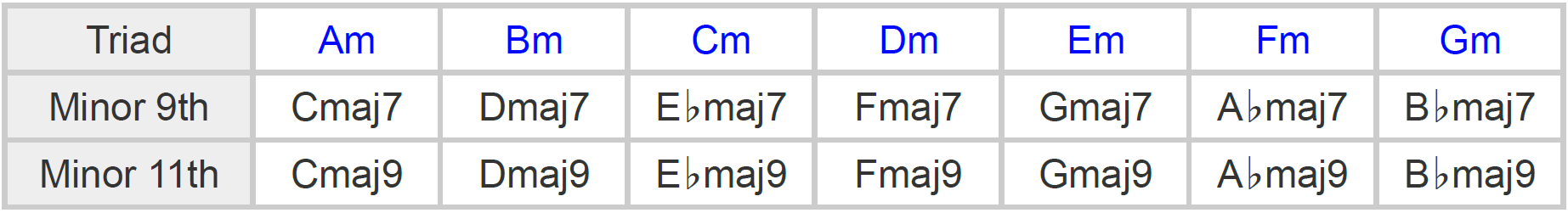

Relative Shapes

It's also worth considering relative shapes. This is where playing a familiar chord shape over a different bass/root note creates a completely different chord.

For example, if we play a major 7th shape on the minor 3rd of, or 3 frets up from the chord root we want to play, we get a minor 9th chord. If we play a major 9th shape on the minor 3rd, we get a minor 11th chord.

Using the table below, we can see, for example, that if we played Cmaj7 over A (or Am), we'd actually be voicing an Am9 chord...

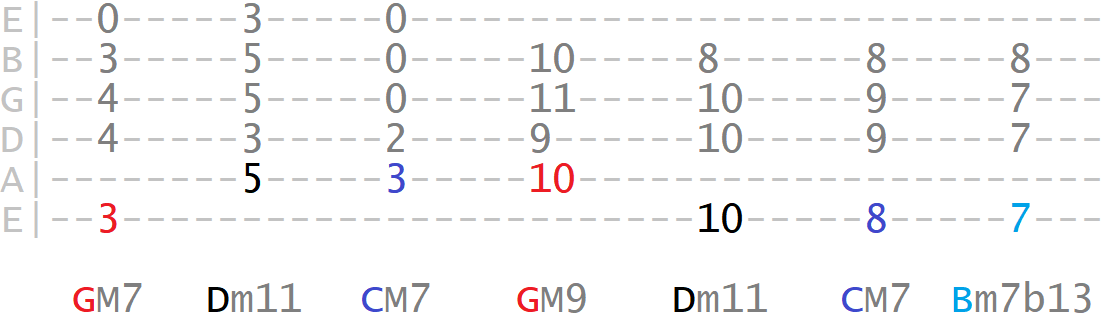

Keeping the low E string open as the root, here I'm playing Em9 using its relative Gmaj7 shapes...

And here I'm playing Em11 using its relative Gmaj9 shapes...

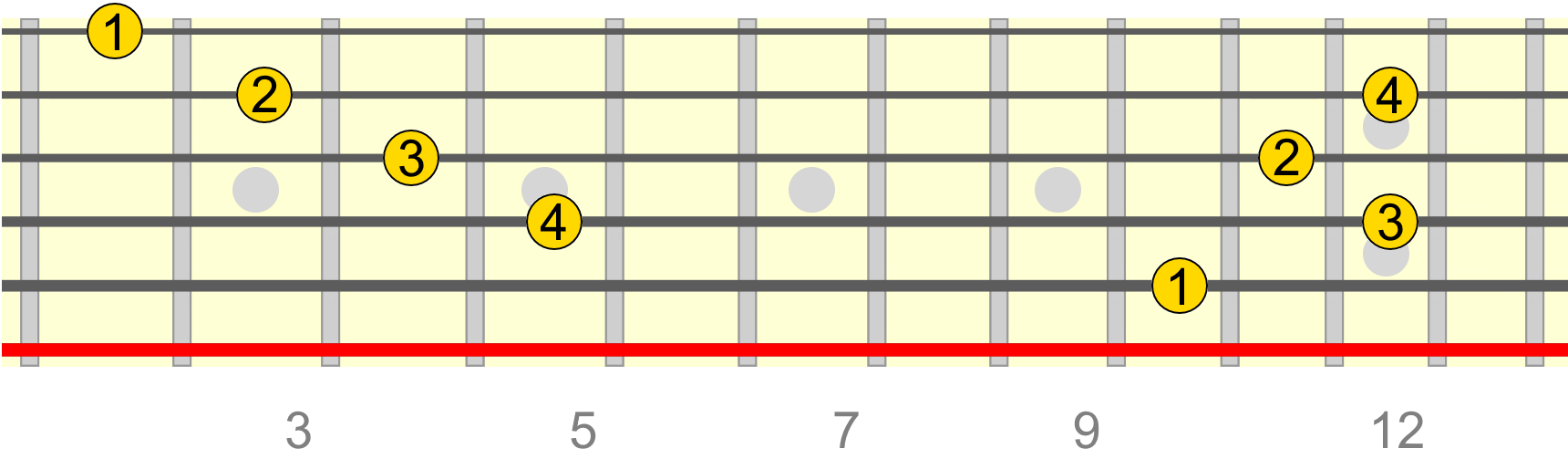

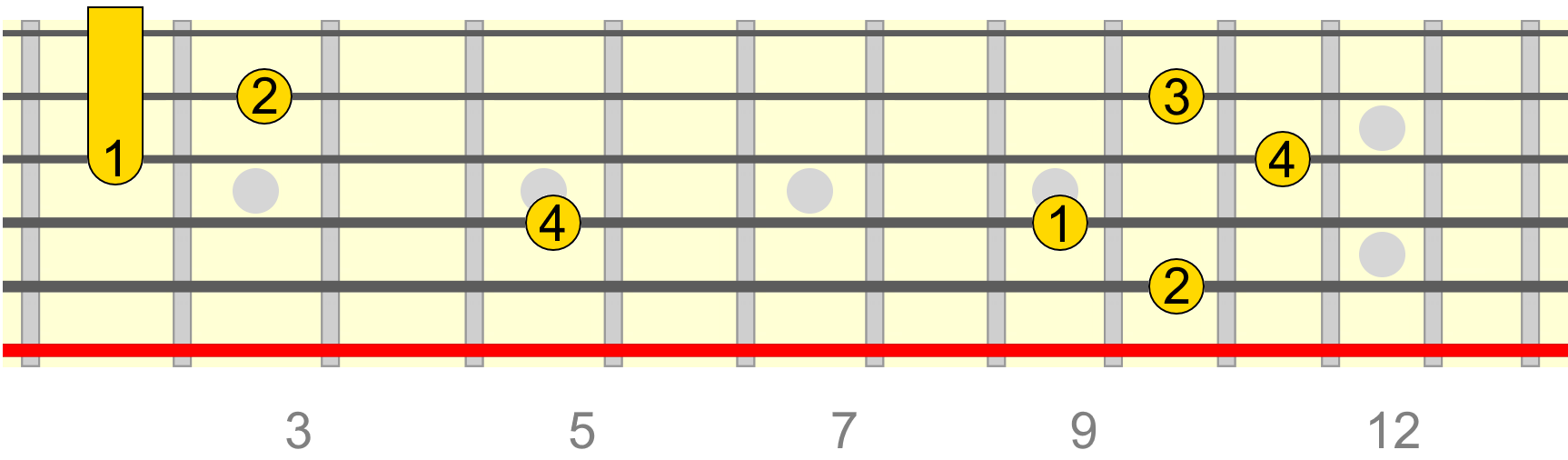

Extended Minor Chords In Progressions

Now we have a good number of shapes to play with, let's look at applying these chords in a practical context.

Minor 9th & 11th

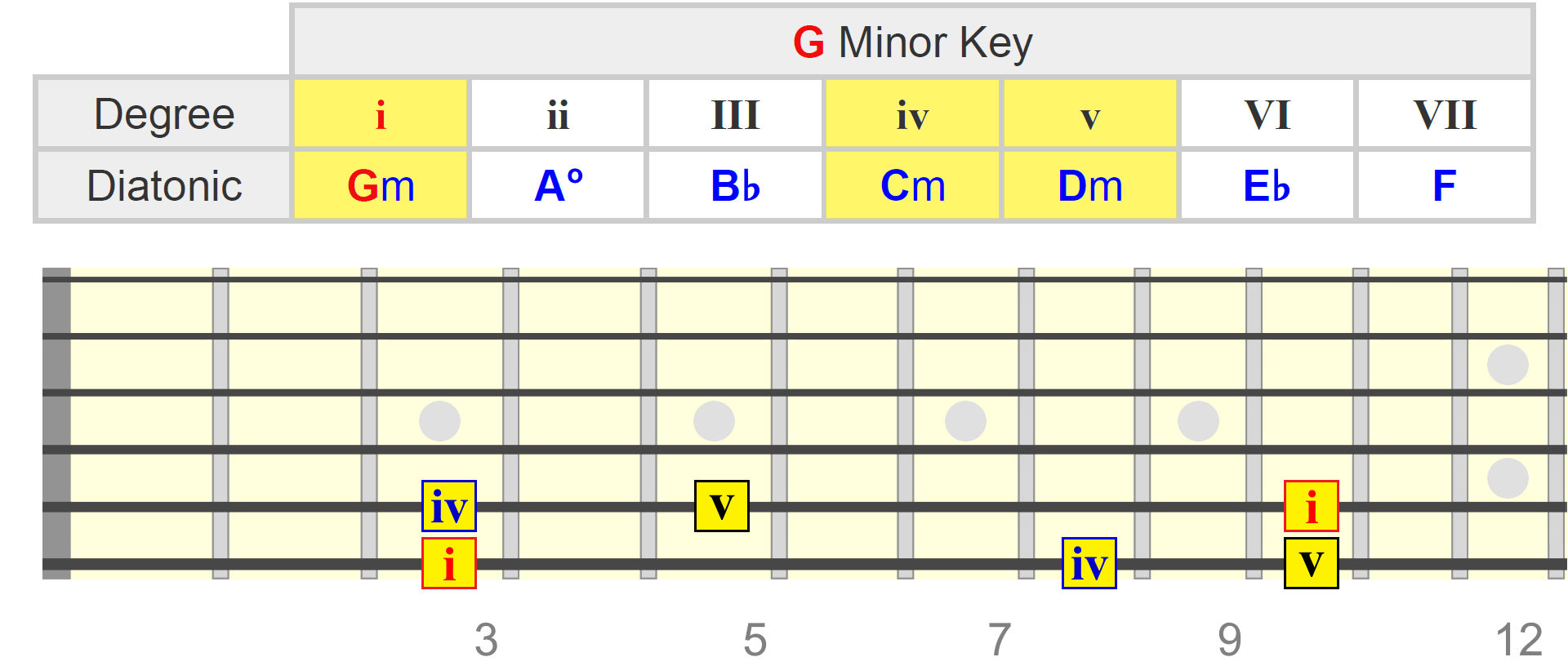

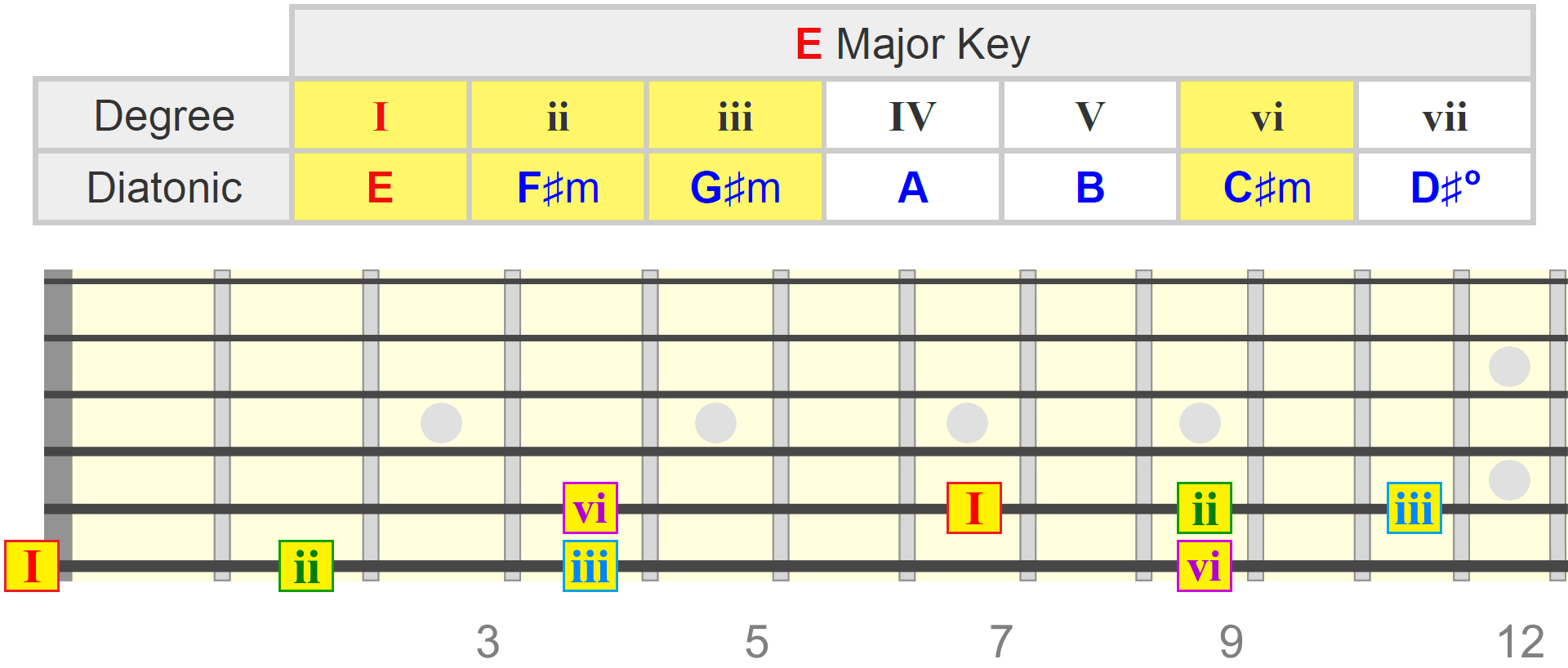

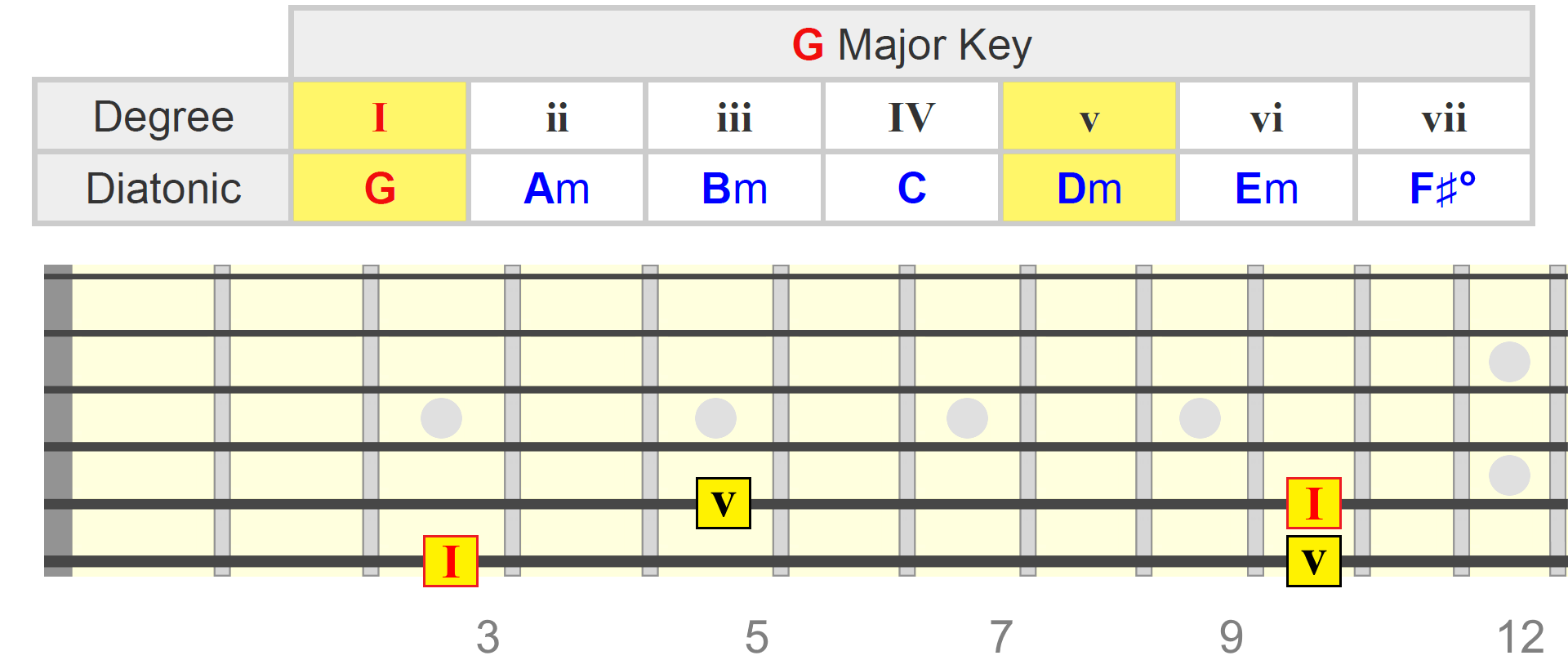

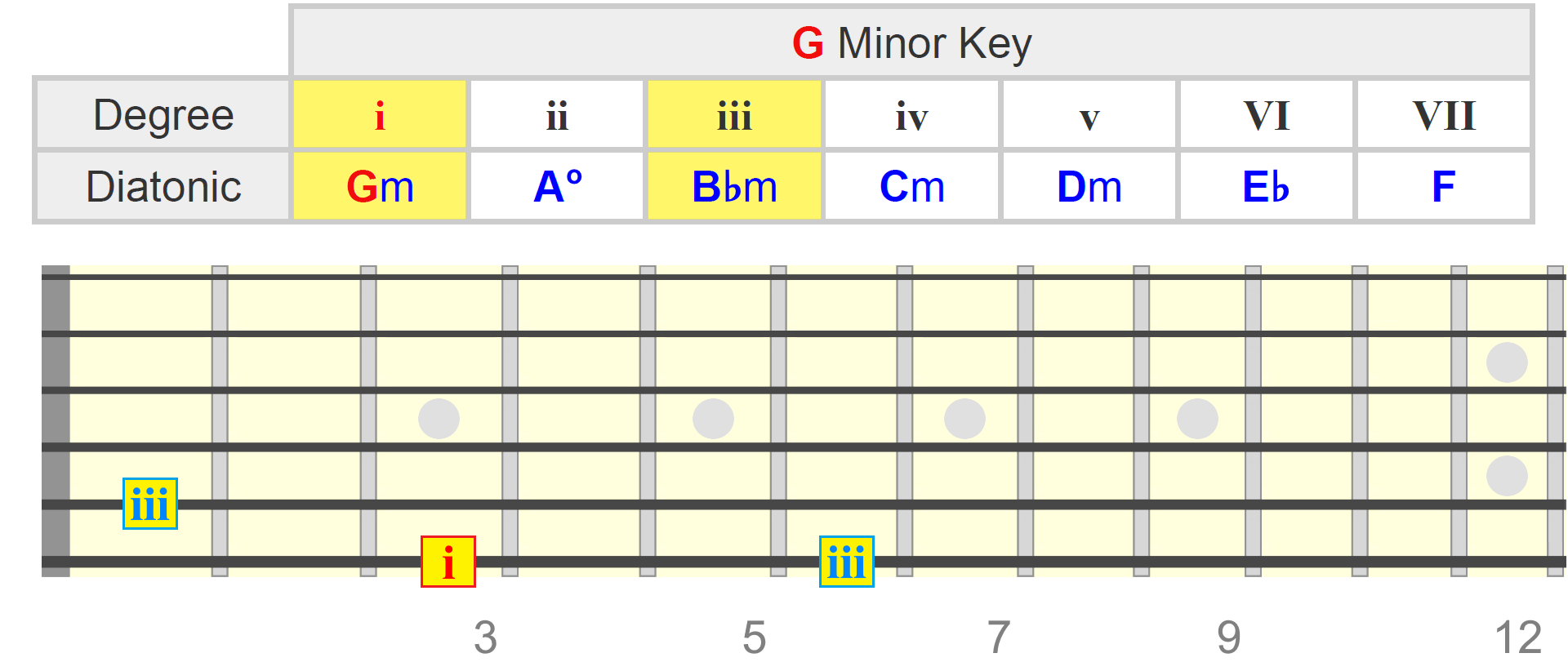

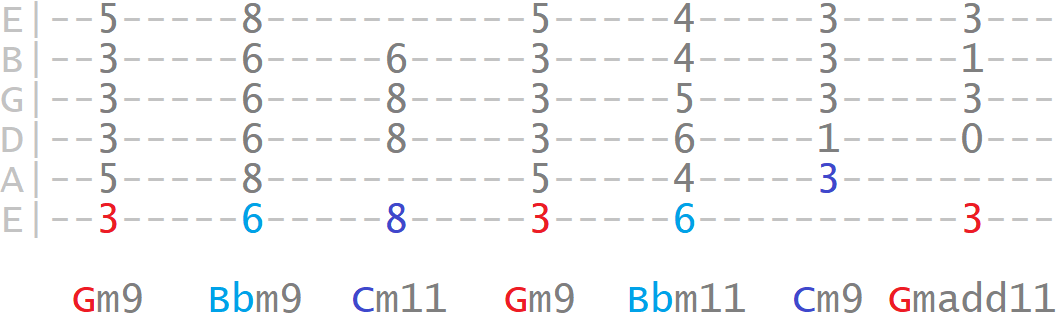

Starting in a minor key, with our 1, 4 and 5 (i, iv, v) chords being minor, we can try using our minor 9th and 11th shapes on these root positions. Here are the above chord root positions in the key of G minor...

Tip: Remember, these chord root positions (e.g. 1, 4, 5) form a movable relationship for any key. So it's a good idea to learn this visual relationship of chord degrees in different keys.

Below I'm playing through this 1 4 5 minor sequence (in the key of G minor) using m9 and m11 shapes from earlier...

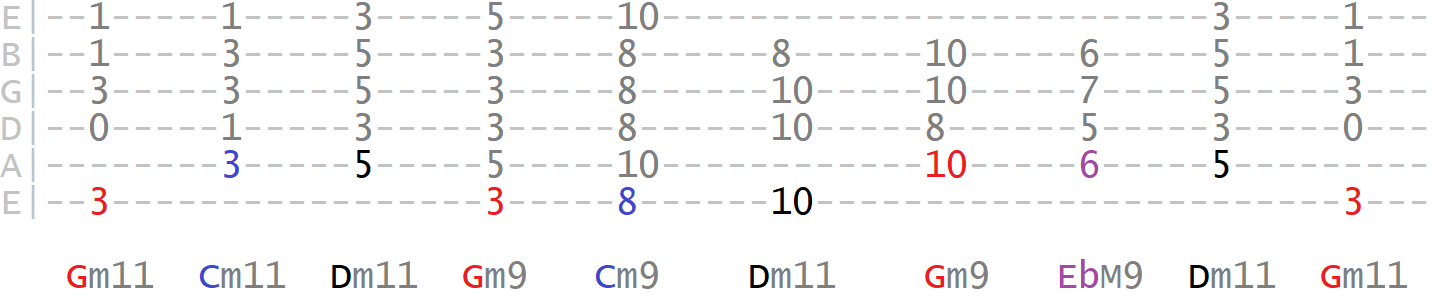

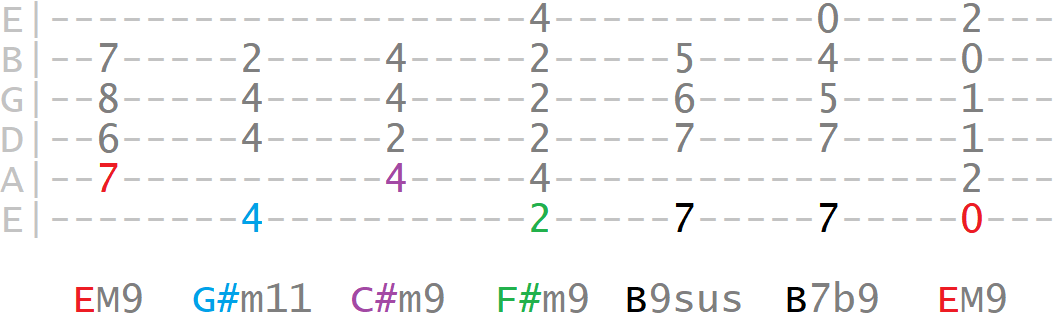

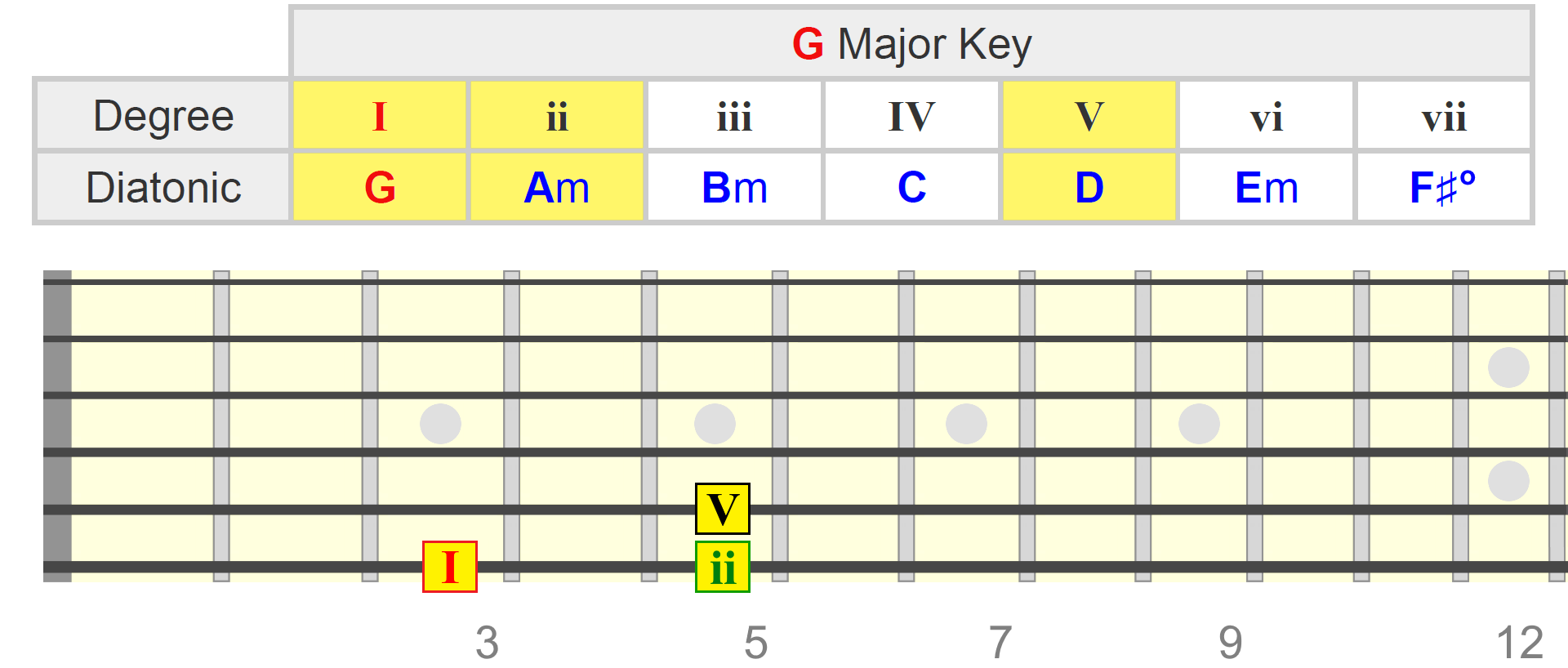

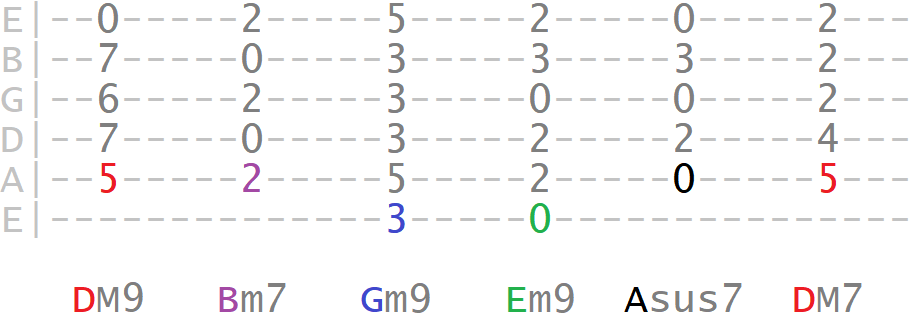

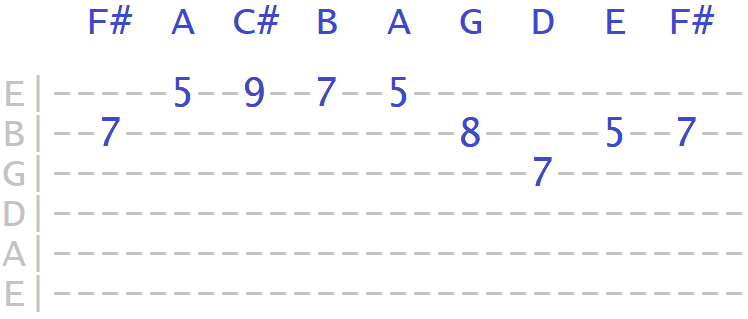

And in a major key, we have the 2, 3 and 6 (ii, iii, vi) chords as minor. Here's how these chord degrees would be positioned in E major...

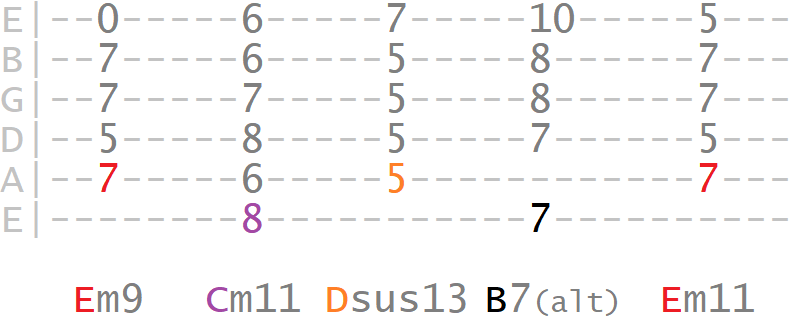

Again, I'm going to play out a sequence (in E major) using extended minor shapes on the 2, 3 and 6 degrees...

We can also place a m11 on the 7 (vii) chord in major keys, as an alternative to the diminished chord. The 7 chord root can be seen as one fret down from the tonic root.

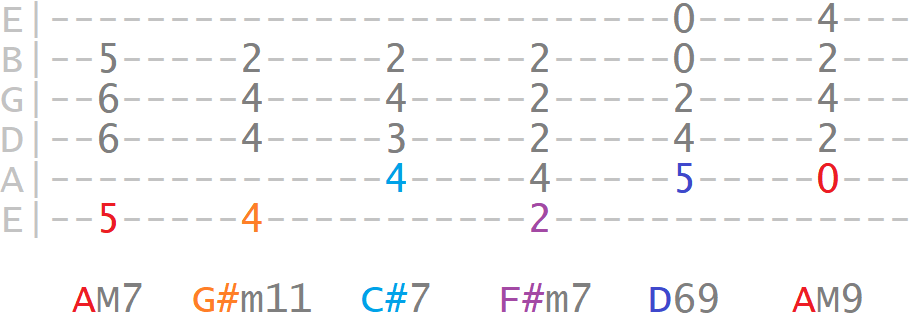

An example in the key of A major, with G♯m11 as our vii...

Already we can hear how using these extended minor shapes gives our minor and major key progressions a more soulful depth and colour.

Minor 7th Flat 13th

The m7♭13 chord can be used in a few ways. It naturally occurs on the 3 (iii) chord in major keys. An example in E major, using G♯m7♭13 on the iii position...

In minor keys, the m7♭13 chord naturally occurs on the 5 (v) chord. An example in the key of C♯ minor...

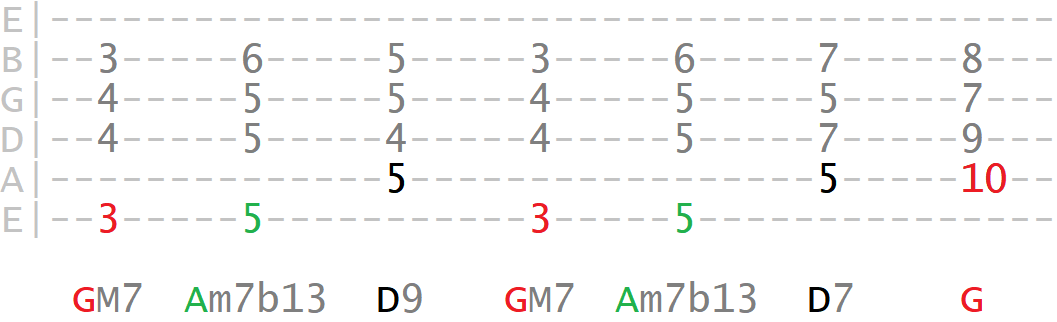

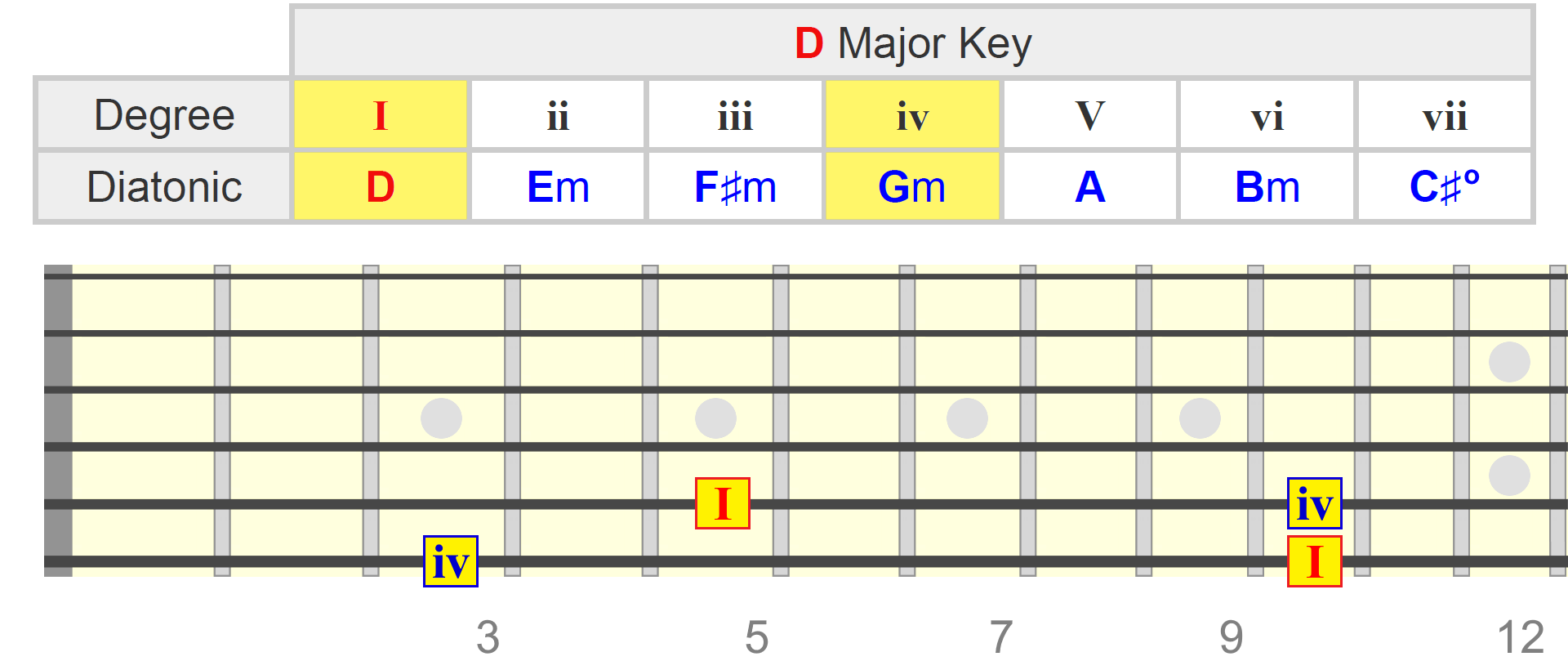

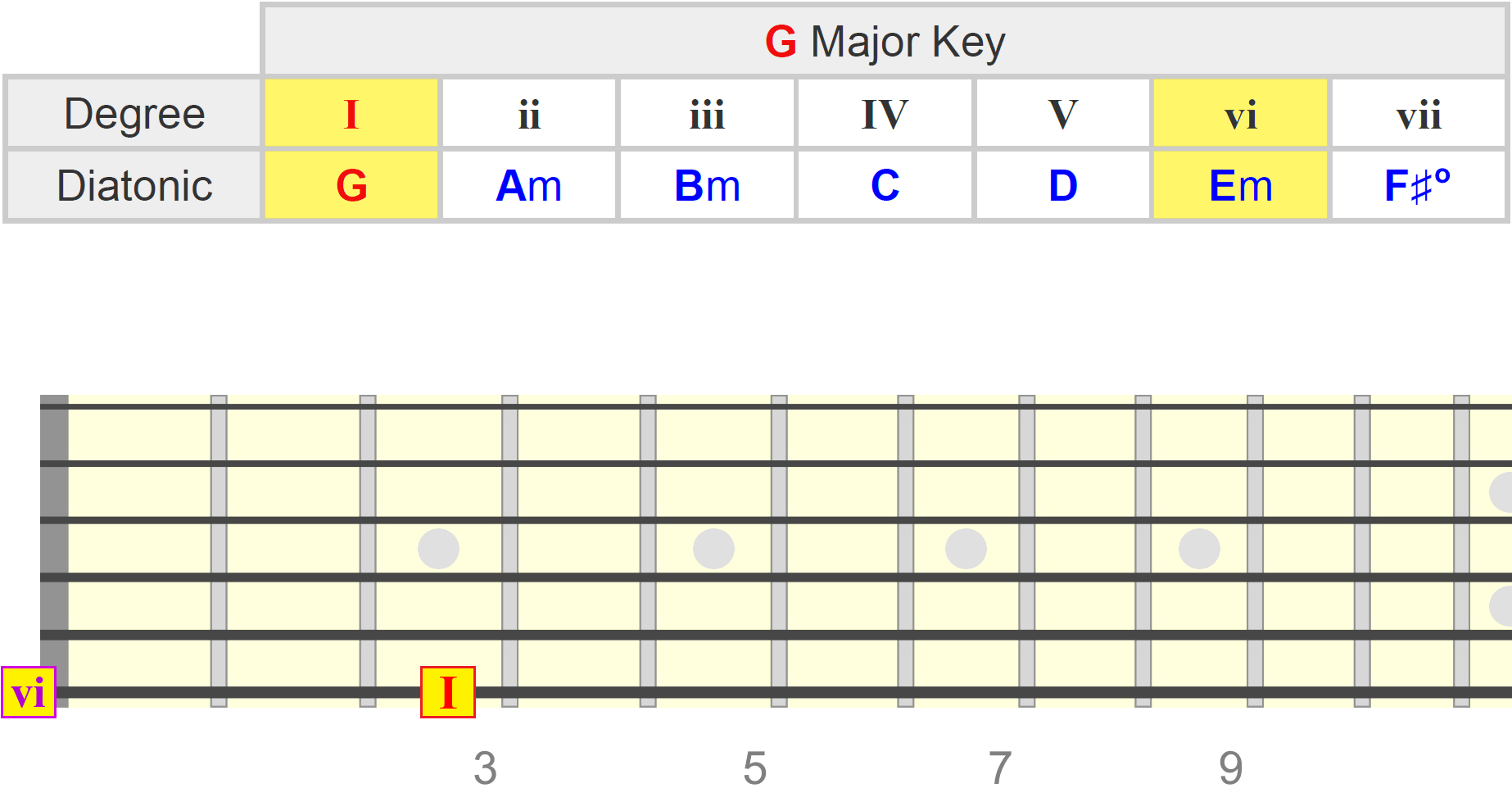

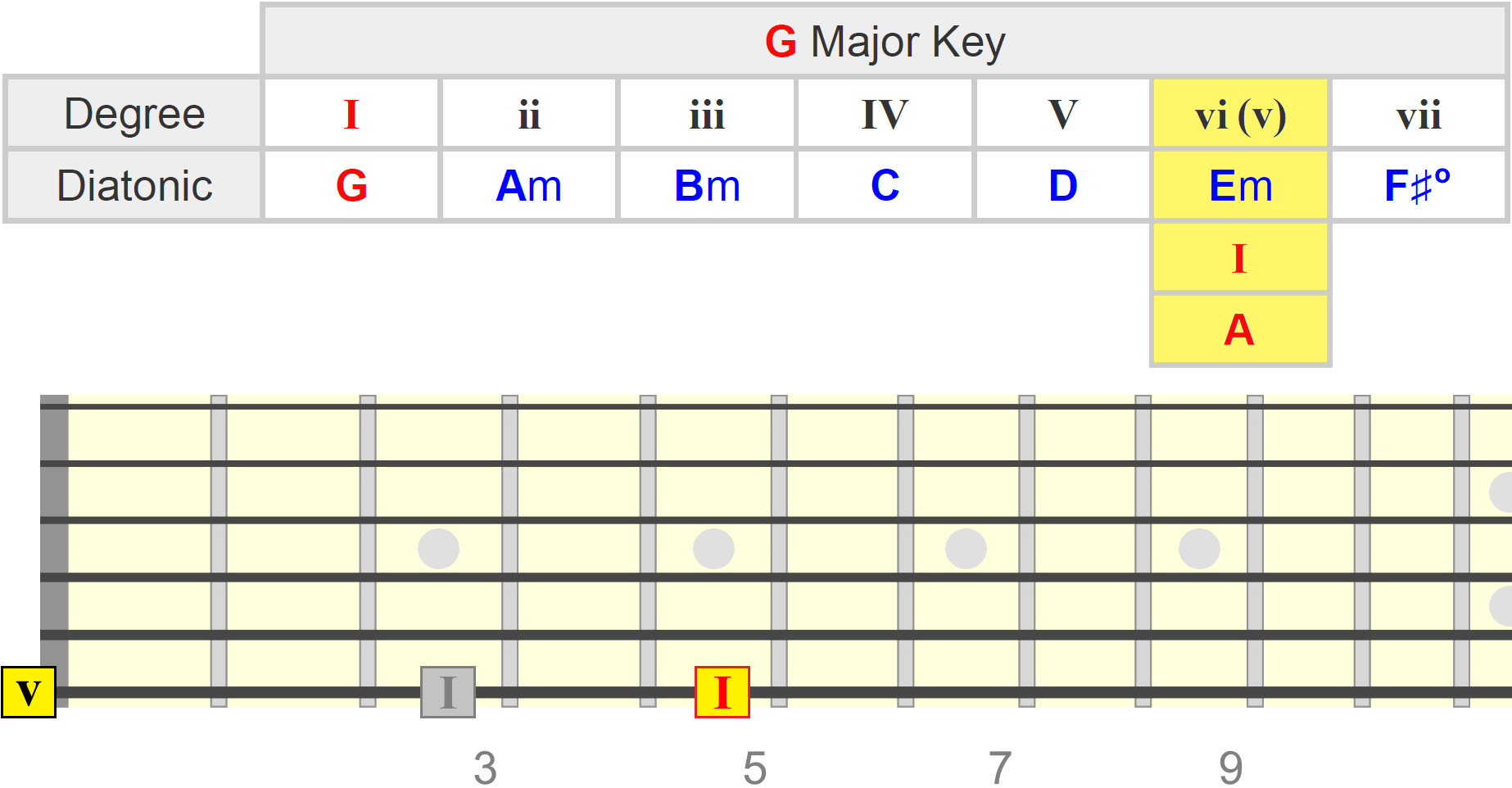

We can also use a m7♭13 on the 2 (ii) chord in major keys, typically as a pre-dominant chord, or as part of a ii V I sequence. Here are these roots in the key of G major...

This works because the ♭13 of the ii chord has a voice leading function either up or down to tones within the dominant or 5 (V) chord...

Parallel Major-Minor Substitution

We can substitute any of the major chords in our diatonic progressions with minor. Sometimes these chords might be seen as borrowed from a parallel key, but we'll get more into the theory behind that another time.

For example we could replace the 4 (IV) chord in a major key, naturally major, with a minor 9th chord. Example in the key of D major, with Gm9 as our modified 4 chord...

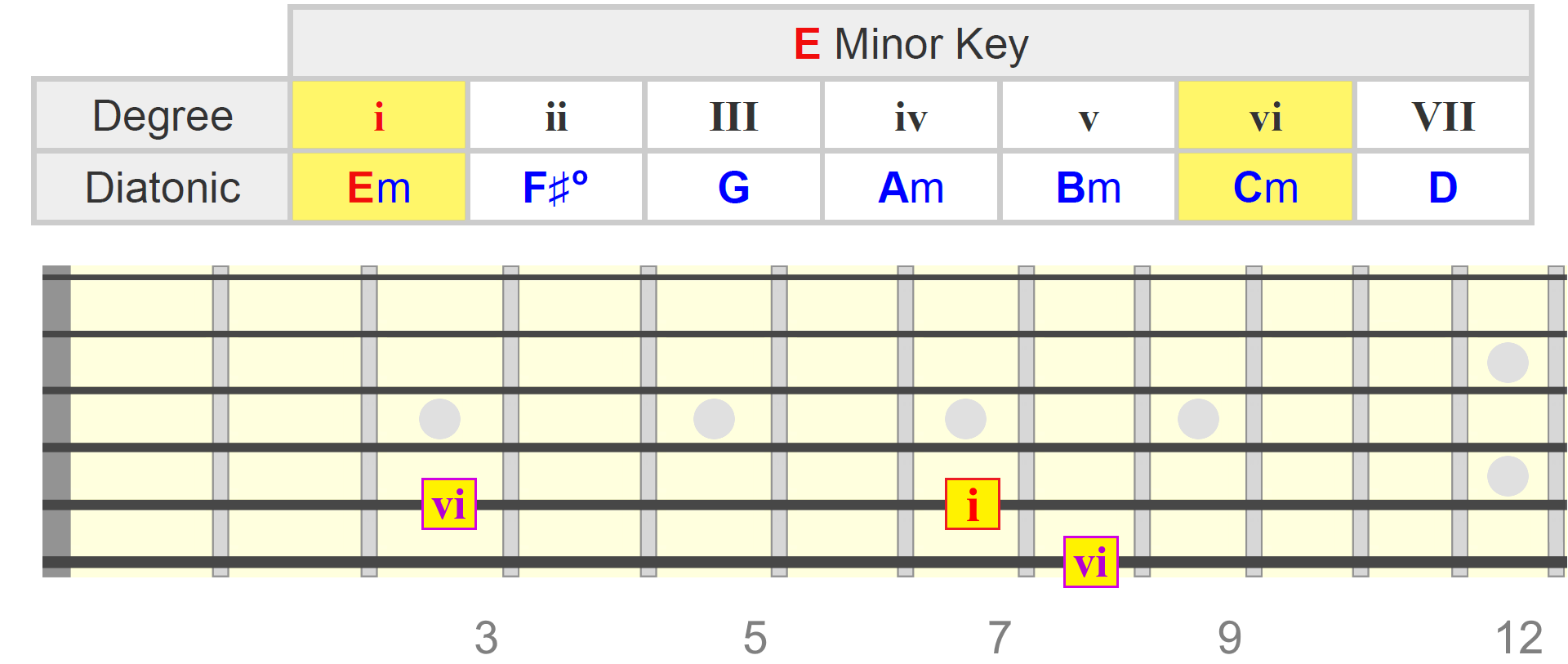

In a minor key, this is the equivalent of making the 6 (vi) chord minor. Example in E minor using Cm11...

We could even replace the 5 (V) chord in major keys with minor. This might seem counter-intuitive, since we're used to hearing the stronger dominant 7th sound on the 5 position. But using a minor 9th or 11th as the dominant gives it a more relaxed and open feel...

In minor keys, try playing the 3 (III) chord as minor, such as this example in the key of G minor, with B♭m9 as our 3 chord...

Voice Leading & Reharmonisation

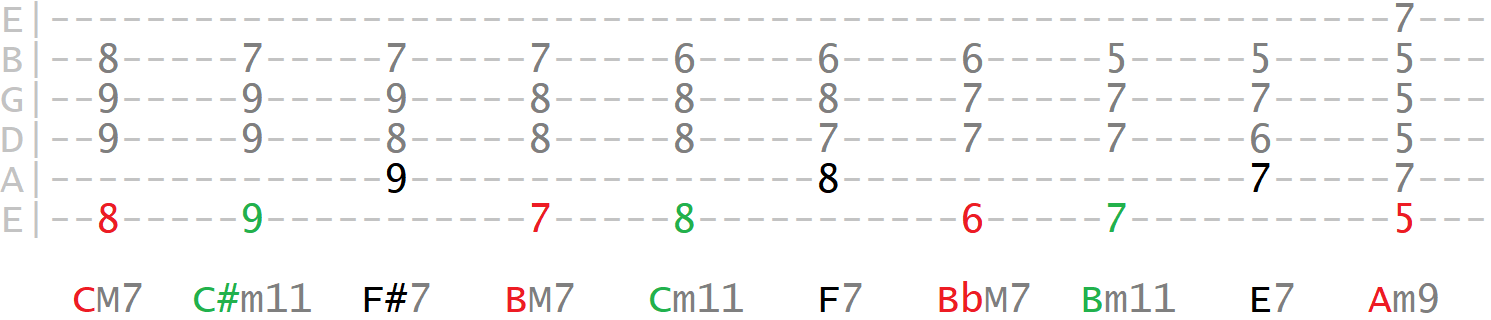

Voice leading, by its simplest definition, is where we form a melodic sequence through our chord changes, typically using the top notes of the chord to form the melodic line. We can then reharmonise this melody by changing the chords we use underneath it.

Our extended minor shapes can help us with this reharmonisation.

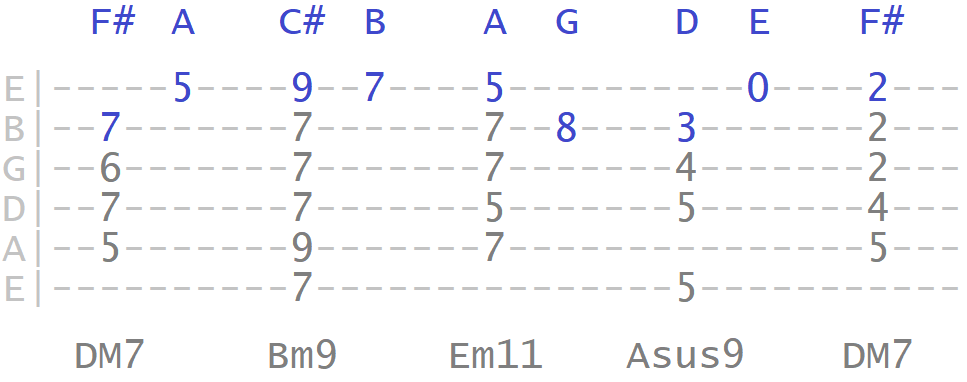

For example, take this simple melody...

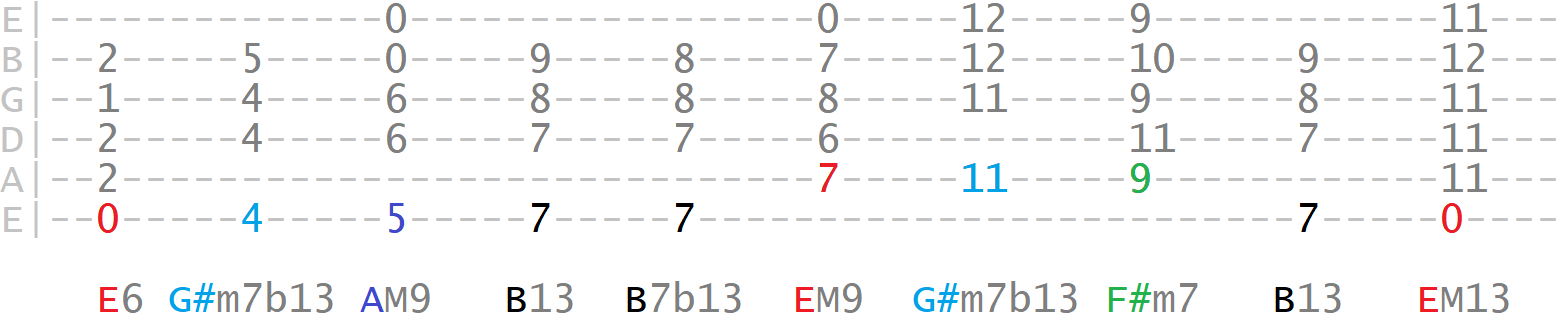

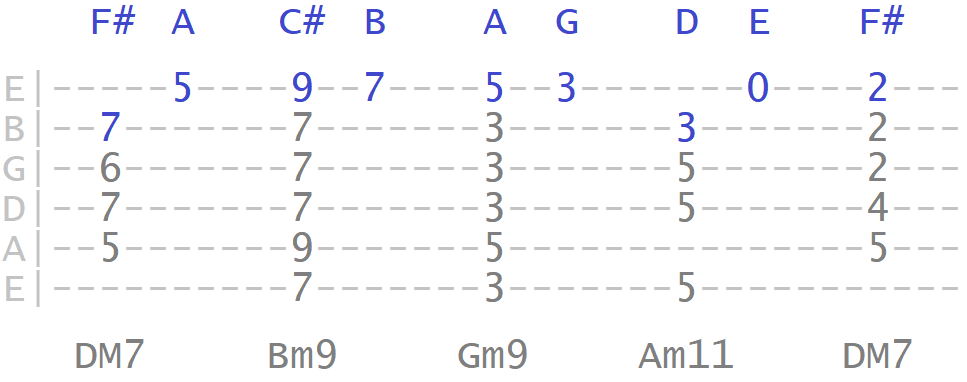

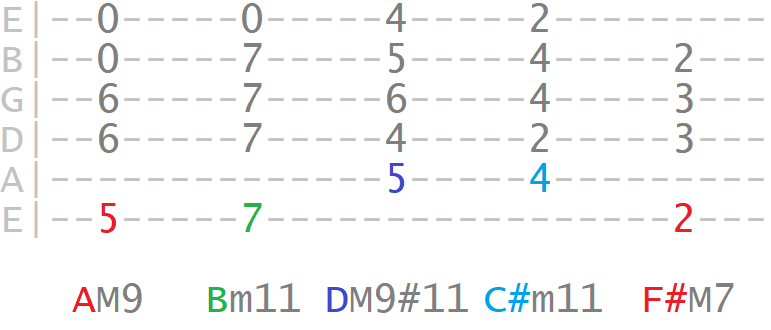

Now let's play an interpretation of this melody with the chords underneath it. The blue numbers mark the melody notes within the chord shapes...

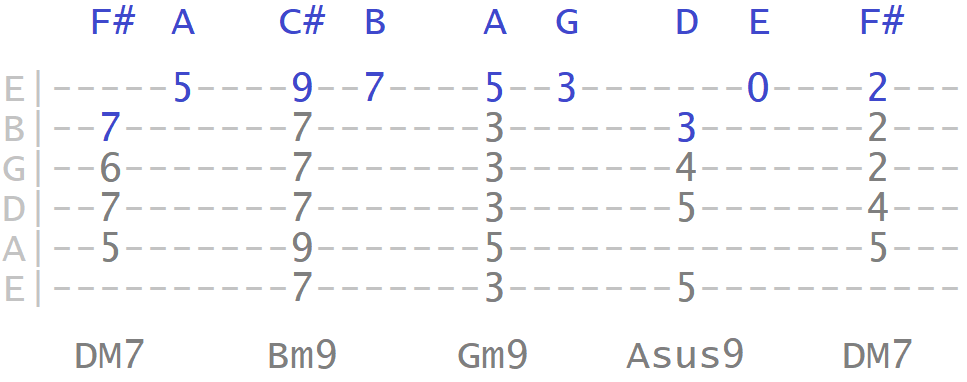

Let's now reharmonise this melody, swapping out Em11 for Gm9...

Notice how the melody remains the same, but the chord sequence underneath it has changed.

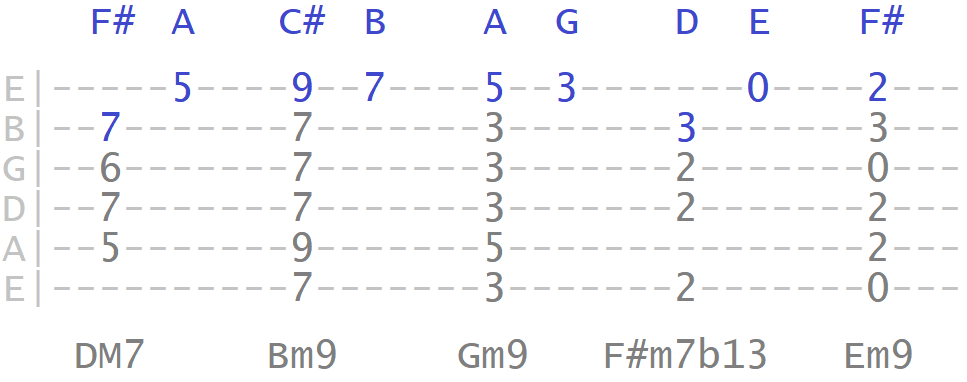

Another reharmonisation, this time using Am11 in place of Asus9...

This time using F♯m7♭13 in place of of Am11 and Em9 in place of our final Dmaj7...

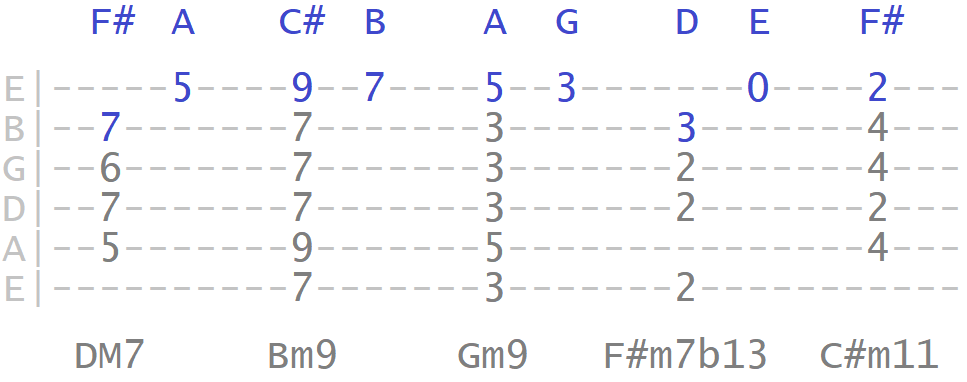

This time using C♯m11 at the end, creating a key change to a new tonic (more on key changes shortly!)...

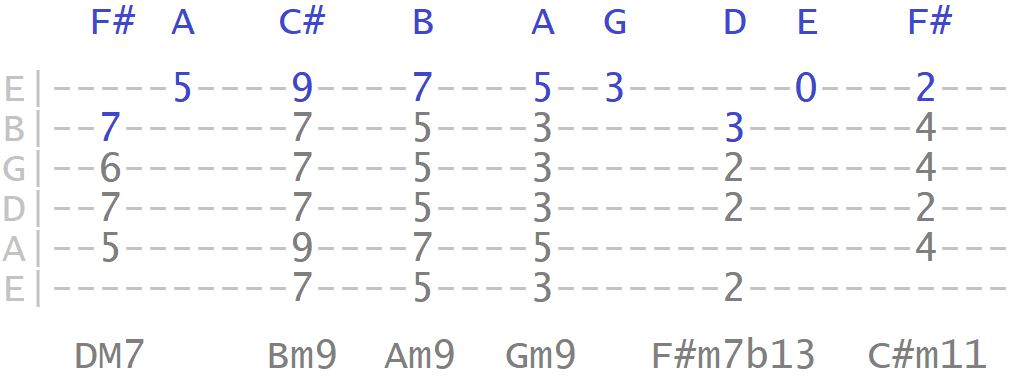

And finally, adding in Am9, touching on the 4th melodic note of B...

So as you can see and hear, these extended minor shapes give us a good deal of flexibility for voice leading and reharmonisation options. We'll look at these concepts in greater depth in another lesson.

Modulation / Key Changes

On the subject of modulation, a lot of what we're about to cover will be complemented by my lessons on dominant changes and major 7th chords, so please also take some time with those.

Similar to the concepts in those lessons, we can use extended minor chords to facilitate key changes. Let's just look at a few examples.

Minor As The 5 (Dominant) Of The New Key

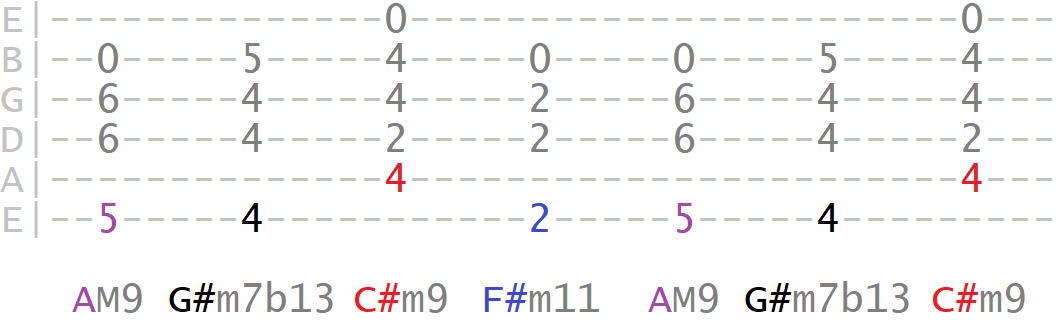

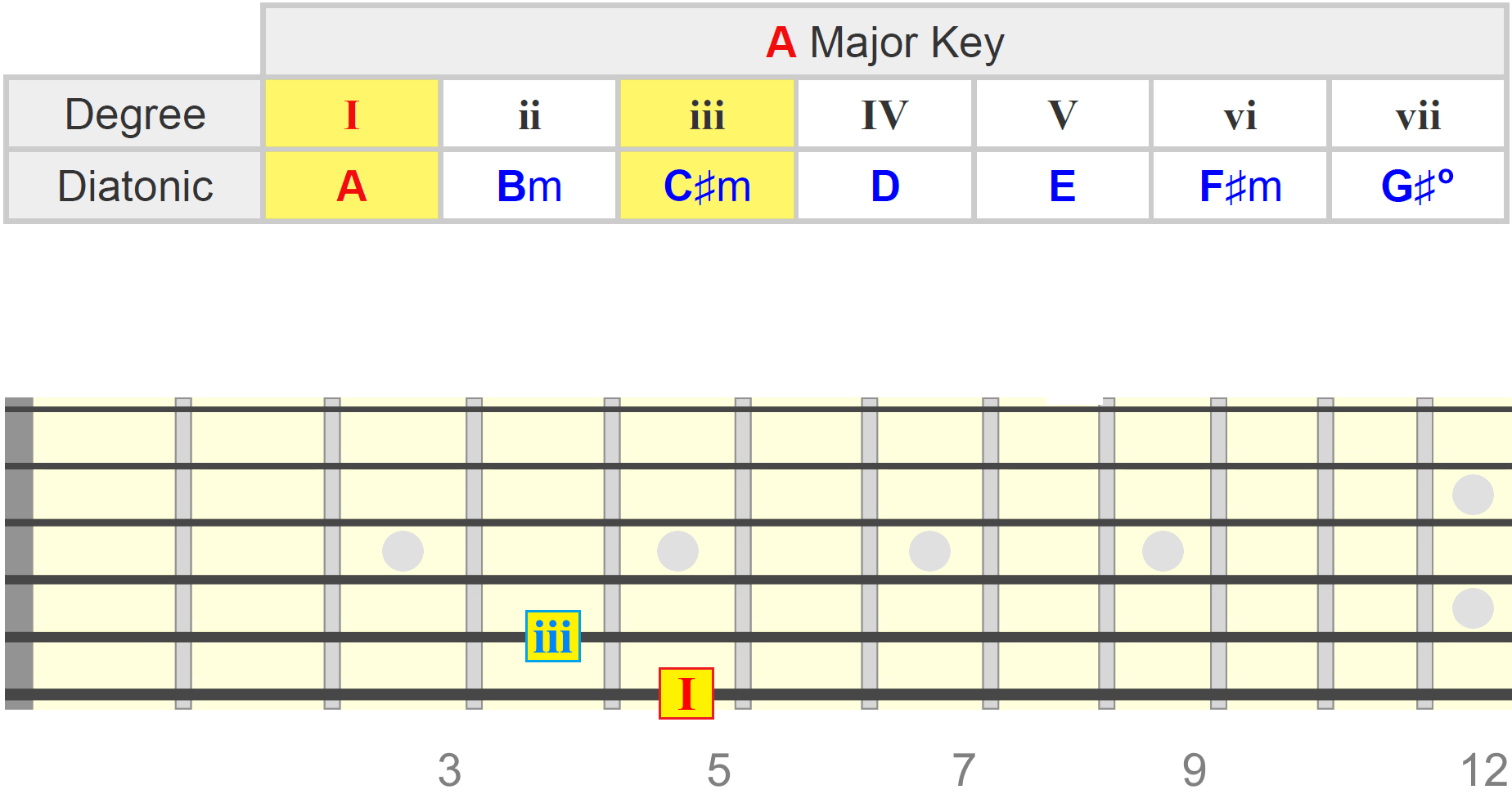

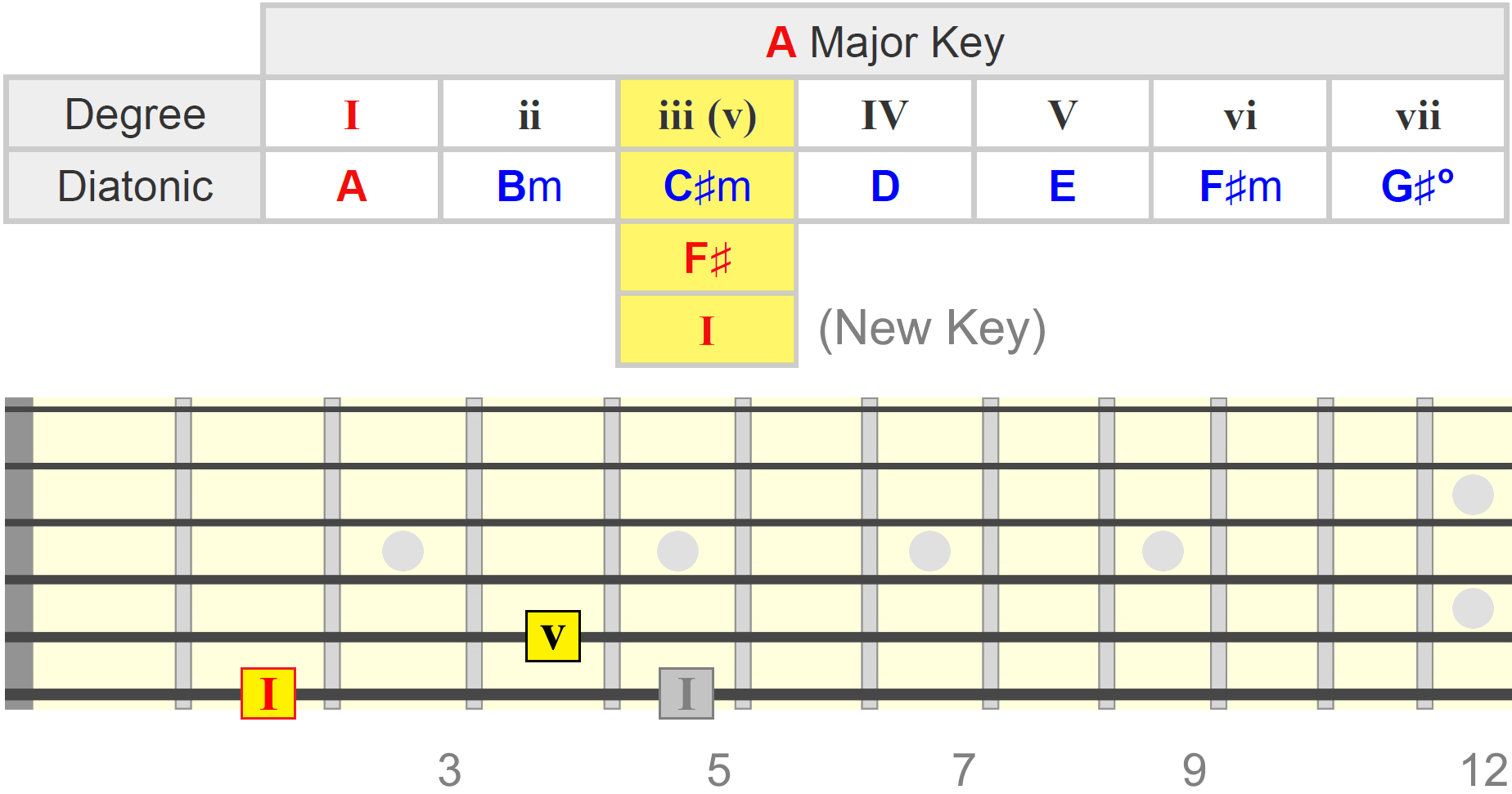

Let's say we started in a major key and wanted to change to a different major key. One option is to use the 3 (iii) chord as the 5 (v) of our new key. In this example, starting in A major, we build a minor 11th chord on the 3, or C♯m11 in this case - this then becomes the 5 of our new tonic of F♯ major...

A similar example, starting in G major. This time we use the 6 (vi) of the original key as the 5 (v) of the new key. Here I'm changing from G major to A major via Em...

Parallel Key Modulation

We can make a parallel key change from major to minor key on the tonic position.

Any chord in our original key can make this transition comfortably. Here I'm starting in G major and resolving to G minor from the original 4 (IV) chord, Cmaj (or Cmaj9 in this example)...

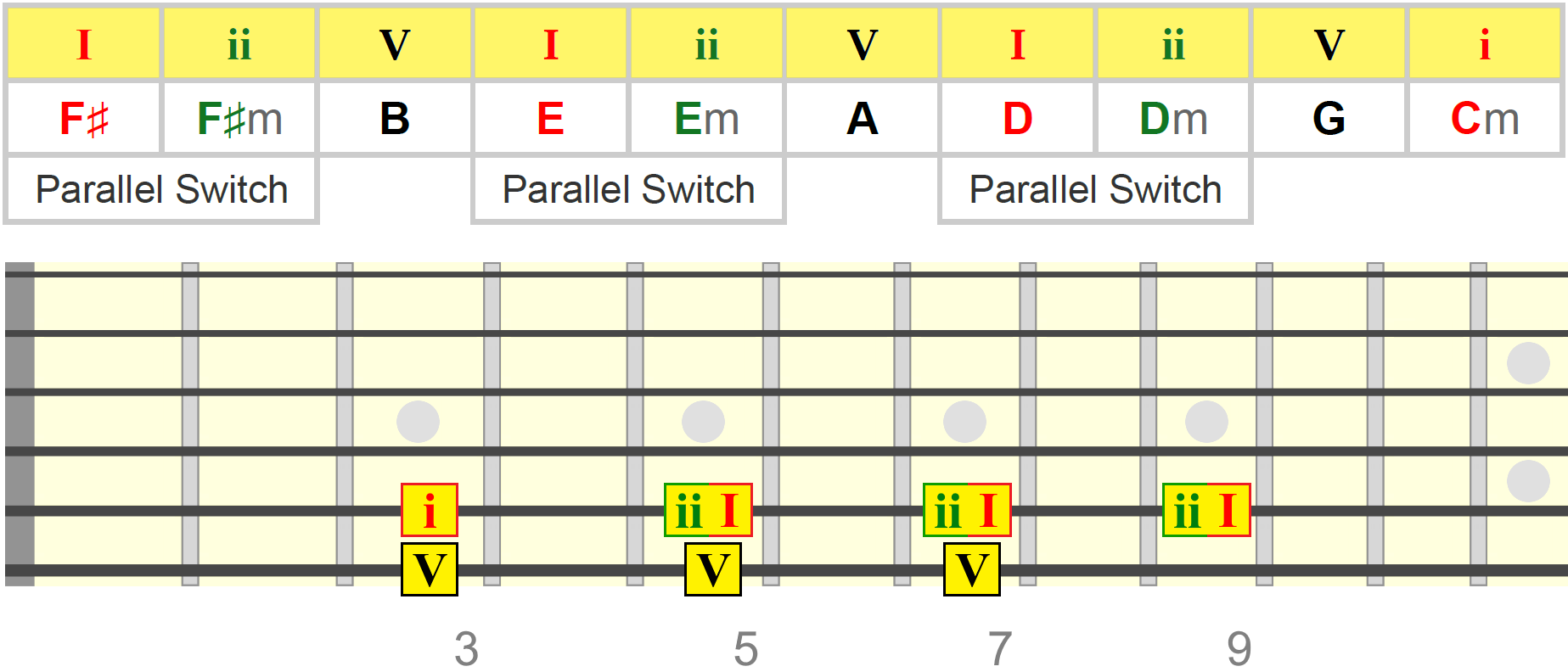

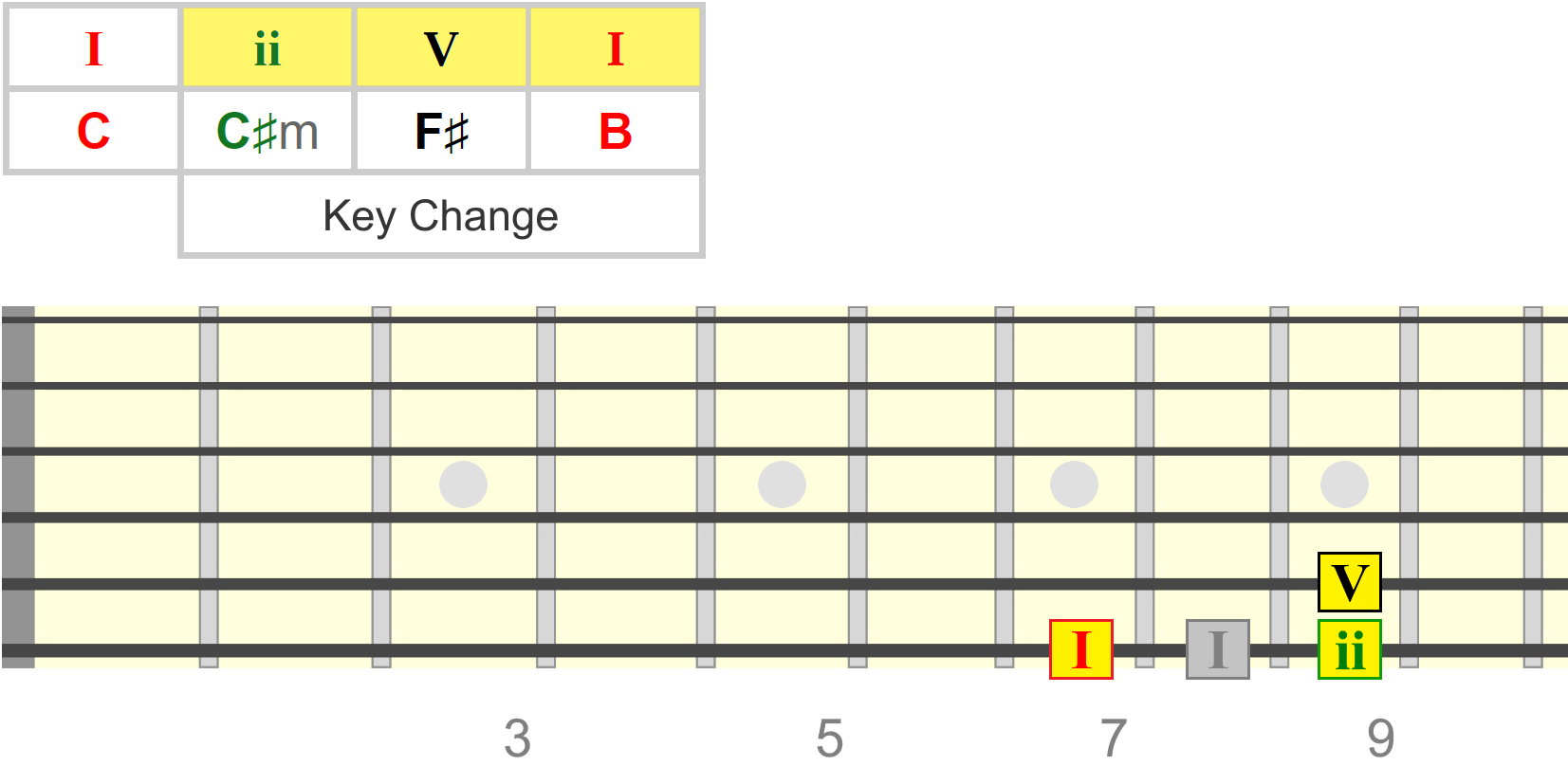

2 5 1 Modulation

Using this parallel switch also allows us to create a 2 5 1 (ii V I) resolution into a new key a whole step (or two frets) down from the original tonic. The parallel minor we switch to becomes the 2 of the new key...

Starting in F♯ major...

Notice how on that last resolution, I resolved to minor. So major and minor are highly interchangeable on the tonic position.

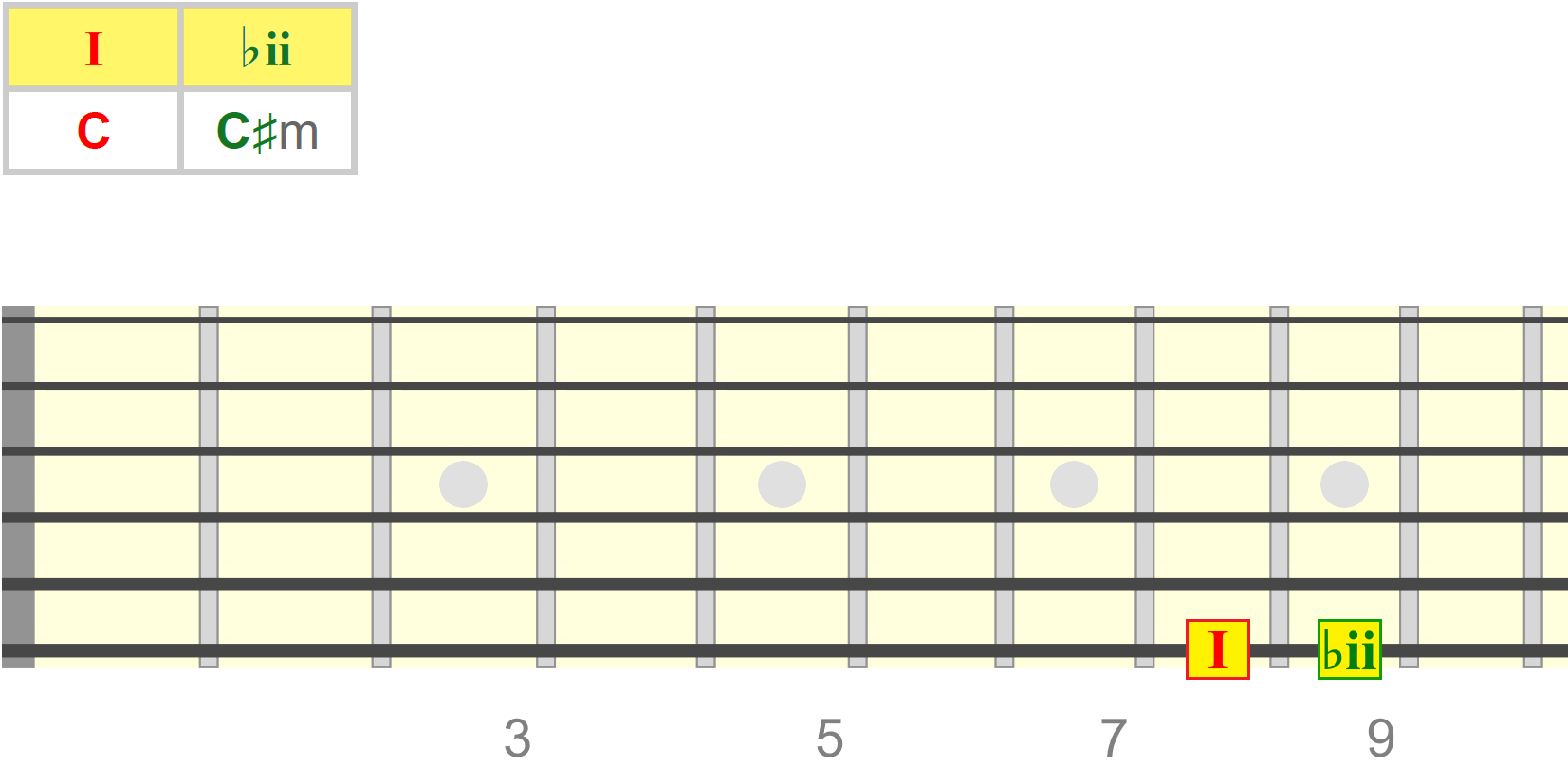

♭ii Degree Modulation

For an even more unpredictable shift in key center, we could position an extended minor form one half step (one fret) above the major tonic root - the equivalent of the flat second (♭ii) degree.

Example starting in C major, modulating to B major...

In Summary

Of course, there are many more examples of how these minor chords can be used in progressions. But I hope I've inspired you to experiment and come up with fresh ideas for your songwriting.

- Experiment with replacing regular minor and minor 7th chords with the extended shapes we learned.

- Replace major chords in a progression with minor and see how it changes the sound (though don't overdo it!).

- Try reharmonising melodies using extended minor shapes (where the top note of the shape voices the melodic note).

- Know that, wherever you play an extended minor chord, key changes are possible.

As always, thank you for your time and patience!